I. Moss to Mozart

The fire tree is now a moss tree. The leaves which had it standing in a pool of fire have dropped and not been cleared. Assimilated into silt, they make mud of the road. The tree stands in its own delta.

Moss clumps on its torso, way past the main fork.

Moss covers every side of the tree except the east side, which could be mistaken for the north.

More traffic arrives from the west. More pedestrians arrive from the east. The traffic brakes for the lights. The pedestrians talk about walking. I search for birds which become unimaginable.

The lichen is numerous-fingered. If I could have translated piano practice into botany, the lichen is that Mozart phrase my left hand trialled endlessly. The lichen is in A major.

II. First Person Arboreal

The fire tree picked out in its leaflessness by sodium lighting looks like things other people may not have seen: frozen waterfalls in winter, jets of water frozen by strobe lighting. It is pale and I am tired. I lean against it and close my eyes.

Before hearing the sounds far away from us, I must forget the sounds I made getting here; the bough I kicked, the creak of my coat, my feet in the mulch of dropped fire. I close my eyes and listen as if I were looking. Sound will not perform like sight. A road to the south roars like a curve. A road to the north roars stop-start. I feel quite sick. Solitary runners clomp and make awkward diversions around us, bigger than needed just for the tree, for my humanness – not my size – makes the tree bigger. We are obstacle.

How much of what I expect from hearing is touch! The cold wind flips and ripples my hair across my forehead, and it feels like it should be a sound. I fool myself that I am hearing the hedge. It is tinnitus mingling with traffic in a small bay between my left ear and the tree trunk.

I feel you while I hear me as only you allow.

III. They Go Quiet

The marriage tree makes a noise. It has a thick body. When I walk up to the marriage tree, the wind drops. It’s as if all the trees I want to visit in stillness equally want to partake of silence. On this site, dreadfully smug engines whoosh and hoop, regulating the temperature of prohibitive buildings, pushing out the traffic to go drown itself. I used to work here.

Leafy footsteps, light with purpose, one Working Late person at a time, cut through from my left, to my right. My eyes are closed. I am thickly canopied by the marriage tree, even if its leaves are not rustling, even if its roots are pooled in concrete and its body is hedged about so I cannot touch its bark. Skeletal clanks from my left and to my right: bicycles being unlocked.

I want to pretend I hear leaves. I do not. I want to stretch my arms crosswise, as the footsteps and clanking proceed right and left. I do not. I leave hearing a little sound of my coat about my neck. I leave knowing how, when I walked up to the marriage tree, the leaves rustled.

IV. Egrimony to Embrace

The avenue of trees revisited in memory is closed off by gated compounds the size of citadels. For more than two hours I walked widening and narrowing circuits of their alleys and by-ways, always checked by a wall or a gate. I see where the long-desired avenue must be, across the black river; though not exactly. I make a rollcall of distinguished men who, at a knock, might be surprised into kindness. Their names and silvery bodies might let me through the stone courts that control the much greater expanse of dark green slopes leading to water. I think with bitterness of famous poets of the recent past and the unasking present: men who could say, “Let me through. My eyes enrich your vista and my words make clear your water.” Instead of trying words, when my body will have forespoken me, I walk around the access points, following through to their locked inevitabilities; walk over bridges, espying climbing places, aware of surveillance technology that renders quest into criminality; I lock eyes with an all-weather old man standing guard in archaic garb, who seems to know that I am up to something, and I decide to spare him the trouble of doing his job. I gave up on the avenue and did no wrong.

So much noise in my head when the clump of trees arrests me. It is severally woven, hence its ability to hammock a hemisphere of sound, soughing at a height.

Still the traffic and bitter musings mess about in my head.

Bicycles ease over the bridge.

I am positioned like someone about to jump, in order to share the clump of trees’ stillness. There is water between us.

If riders notice, and when walkers pass, we are nothing worth stopping for.

I break into nervousness. Not yet present to the clump of trees, I am afraid of not finding them again. Not much distinguishes them. I count lamp posts. I refer the clump of trees to other, more distant treelines; I hope to match up significant shapes, but night is brushing off oversignificance of any detail. I imagine inviting a quiet friend, anxiously, to this place, and not finding it at once. I was eager for trees; and frustrated. I must be careful about exciting another eagerness I cannot satisfy.

Gradually the road traffic becomes a milky ribbon, east and west. Gradually the bridge traffic becomes a flow to which my back is turned. Neither stream of traffic sound borders me in any way that constitutes my borders. Gradually the clump of trees assumes me. There is front sound and back stillness. They do their thing. I lean in.

V. Tree of Approximation

Listening to a tree with another person, listening with a tree to another person; listening or hearing? Who conducts attention to the rim of the sky? Start there. Start twice, and that is twice again.

This time the thick canopy of the marriage tree is rustling. My ears welcome and embrace the sound. It slips down much closer in hearing than sight would have allowed it to reach from the curve of leaves above. My eyes have closed, you see. My heart is thudding; my body knows that, not by sound. Small plants were trembling; I remember them, but they do not add in their small sounds. Footfalls one way and a single dry leaf the other way do skater tricks of sound, up and off from the ground, more volume in the air than you would think from looking at them.

More than you would think. From looking at them. We love. This tree.

VI. Intentionally Wolf-Inclusive

It is raining when I hurry to seek out the clump of trees. My coat is made of a loud material. As I move through the dark streets – it is not yet nighttime by the clock – rainfall hits the coat, loudly, from enough different directions as to make it seem that the rain is approaching from different heights. I am a percussive mess when I get to the bridge. None of the student body dotted about with and without bicycles, lingering in virus-friendly groups, makes a sound of noticing; none interrupts the sound of their commingled murmuring, when I climb onto the railings, lean over the scummy river, ignore the glisten, and listen for the trees.

I am listening with the trees.

Rain hits the water from enough different directions as to make it seem that the water is approachable from different heights. Rain is being shaken off the black weave of coniferous branches. I cannot pretend to hear it. I can only pretend to hear it.

I think myself into the further reaches of the weave, then move closer to the clump of trees. I do hear droplets. My attention shakes off the clank and gossip of the bridge. Awareness branches all over my coat, and in the drumskin hollow of my ears, very lightly, hitting and rolling away again.

I am a musical instrument of the trees, and it is raining.

VII. Flashback to Belfast

There is no way of being shocking that shocks. An artist’s shock is an expected delivery. Ready to be absorbers, the consumers of art; they’re hyper-absorbent. You know what is shocking? Care. Care is shocking. Attention is shocking. Being soft and slow. Radical care is the new revolutionary. Forgive me, for I have sloganized in the café, where my colleagues long ago reconciled kindness and subtlety. (This is happening before the plague.) My present colleague sits flaming quietly with tenderness and the students, like so many New Year lamps, bend and flicker inwards. We are sitting in warmth.

There followed (in a colder city, water between island and island), during the permitted exercise of lockdown, six instances of stillness with trees. You don’t hear in order to listen. You listen in order to hear. Start with the furthest. Name, note, move on. Move in. You are hearing your own interior, yes, even the mindbuzz randomizer, even the bodyshameful procedures. You are not hearing interiority to the exclusion of anything else. Your interior soundscape becomes audible in relation to everything else. Surround sound is a condition of surround silence.

I station myself by particular trees, and start.

Case Notes by David Stavanger

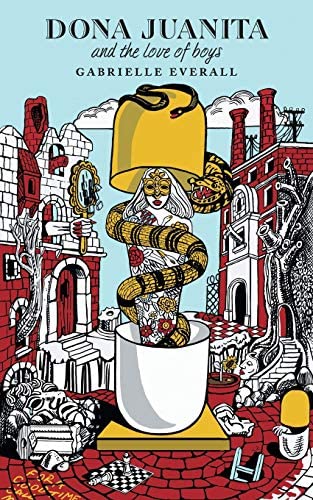

Case Notes by David Stavanger Dona Juanita and the Love of Boys by Gabrielle Everall

Dona Juanita and the Love of Boys by Gabrielle Everall