Aboriginal Protection Acts

The Aboriginal Protection acts were legislations by Australian States and Territory Governments to control all aspects of Aboriginal people’s lives on Christian missions and government reserves in the late 19th and 20th centuries.

The acts differed depending on the racial politics of each state or territory, but there were common treatments that affected all Aboriginal people under state control. Tasmania and the Australian Capital Territory did not technically have legislations called protection acts, but they did have similar policies. These policies included racial segregation, assimilation, forced westernisation, restriction of cultural practices, removal of Aboriginal children, servitude, and control of employment, finances and wages.

Under the acts, Aboriginal people were racially segregated from European Australians on government controlled Aboriginal missions. If an Aboriginal person needed to leave the mission they would have to make a request to the government to leave for work, shopping or medical reasons. In all states except Victoria and Tasmania, individual exemptions called Certificates of Exemption or a dog license wwere given to a specific person who was considered respectable in European Australian society. These certificates of exemption were still in use in New South Wales until the passing of the Racial Discrimination Act of 1975.

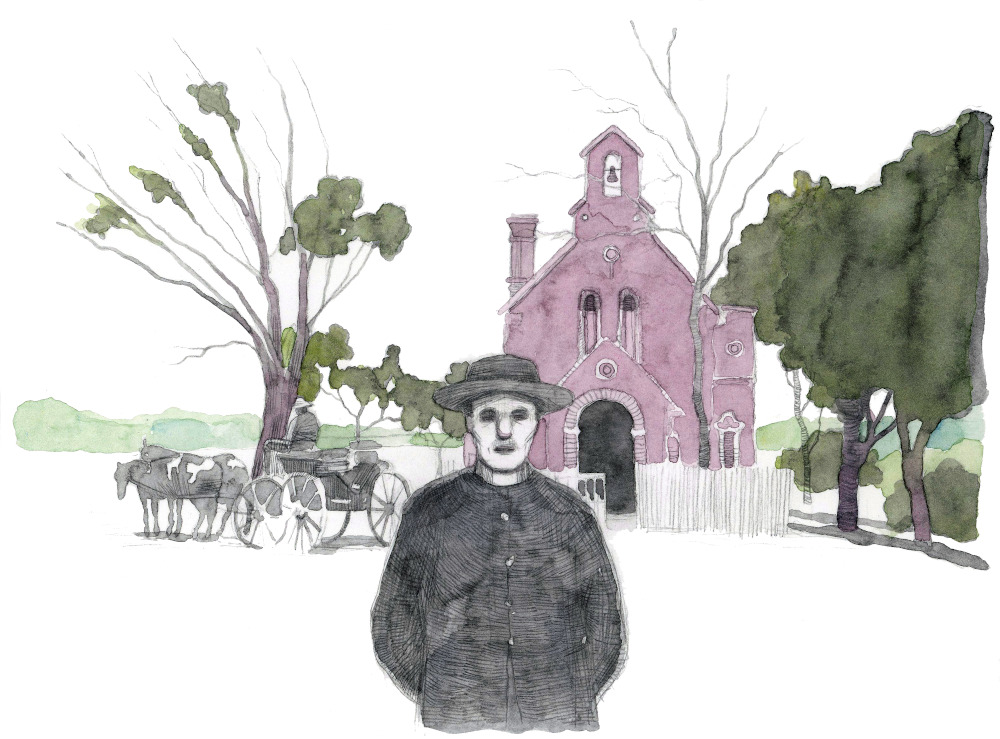

Under the Aboriginal Protection acts, mission managers, protectors and missionaries were given the authority to control the lives of Aboriginal people. They stopped the speaking of Indigenous languages and cultural practices, with Aboriginal people forced to speak only English and to practice Christianity and western culture. The mission authorities would punish an Aboriginal person by restricting food rations and wages, physical punishment, imprisonment and removal to another mission.

Aboriginal women on missions, reserves and in institutions were trained in western domestic life to work as domestic servants in European Australian houses. This servitude ranged from underpaid servants to unpaid slavery. In severe cases Aboriginal female servants were subjected to physical, psychological and sexual abuse by their European Australian employers.

Aboriginal men were employed as labourers on farms such as sheep and cattle stations. In the 19th and early 20th centuries Aboriginal men were only paid with food and accommodation, which is a form of slavery. In the mid-20th century, Aboriginal people were generally paid at a lower award wage than European Australian workers and in some cases the employer and government withheld wages. In 2006, the federal Senate did a report on Indigenous stolen wages and Aboriginal workers could claim their lost income.

The acts gave power to the states to remove Aboriginal children from their parents. During a period now known as the Stolen Generations, tens of thousands of Aboriginal children were taken from their families. The Stolen Generations started in the 1840s in South Australia and Tasmania, where the model of assimilation by removing children from their parents in order to westernise them began. The forced removal of children happened in all other states and territories in the 19th and 20th centuries. Forced removal of children for the purpose of assimilation officially stopped in Australia in the 1970s, but it still continued into the 1980s in Queensland.

The Aboriginal Protection acts officially ended in 1969, two years after the 1967 referendum that gave Aboriginal people the right to be counted on the Australian Census and acknowledged them as official citizens of Australia. However, the acts’ legacy, in particular on the Stolen Generations, still has multigenerational effects on Aboriginal people living today.