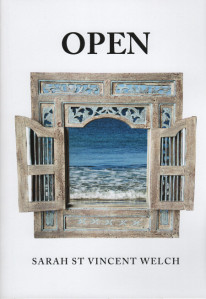

OPEN by Sarah St Vincent Welch

OPEN by Sarah St Vincent Welch

Rochford Press, 2019

Cuando Fui Clandestino / When I Was Clandestine by Juan Garrido Salgado

Rochford Press, 2019

The achievements of the poets who started publishing in the early 1980s in Australia have tended to be overshadowed by those of the generation immediately prior to them. Rochford Press was started in 1983 by Mark Roberts and Adam Aitken, catching the tail-end of the little mag boom of the 1960s and 1970s. During the 1980s it was the imprint of the poetry little mag P76 and also published four collections (by Mark Roberts, Rob Finlayson, Les Wicks and Dipti Saravanamuttu). The press wound down activity in the early 1990s, and nothing more was published until Rochford Street Review started up in 2011, a neat demonstration that poetry makes its own time. Alongside the Review, which will shortly publish its 29th issue, there have been a handful of publications, mostly retrospective: the ‘best of’ compilation drawn from Rae Desmond Jones’ little mag Your Friendly Fascist, and the wonderful festschrift for Cornelis Vleeskens. More recently, with Linda Adair as publisher, the press has focused on current poetry, specifically a series of chapbooks that includes the two books under review: Sarah St Vincent Welch’s OPEN and Juan Garrido Salgado’s Cuando Fui Clandestino / When I Was Clandestine.

OPEN is a first book, though as the biographical note indicates, the author has been writing, both poetry and fiction, for many years. The chapbook consists of ten poems and an untitled prologue. An initial overview will give a sense of the range in what is, after all, a short book. The first four poems evoke a semi-magical atmosphere; the next two, ‘Nintendo’ and ‘He won’t be any trouble’, offer gentle, comic, parental realism, the latter in the form of satire; ‘Archaeology of Gardens’ continues the parental theme in addressing the poet’s own mother; ‘Fox’ returns us to some of the strangeness of the earlier poems, evoking the figure of Vali Myers; ‘821.3 in the old Civic Library’ offers observational, suburban realism (and incidentally is not the only Australian poem to reference that call number in its title: David Prater’s ‘A821.3’ begins, ‘that place where we all someday hope to die / or rot at least’); and the book closes with a freewheeling prose poem on the theme of openness.

It would be fair to say that OPEN took this reader a while to properly appreciate, partly, and somewhat contradictorily, because of this theme of – and the book’s entreaty towards – openness. The emphasis on openness came across, at first, as tendentious, an attempt to shepherd one’s reading of the book in a particular direction, and at worst as a kind of special pleading for the openness of these poems, which was in any case unnecessary. But on further reading, these misgivings were not borne out; only the prologue and the final, title poem could be said to labour the theme, and the rest are left to do their own thing. ‘Open’ is invoked by St Vincent Welch also in a different sense, that is, different from the way we might think of all poetic language as having the quality of being ‘open’, this being open as an imperative. In other words, the book contains a call towards openness. This comes through in a number of ways: the cover image, slightly reminiscent of a Magritte, depicting rustic windowshutters thrown open to reveal an interior ocean; the title poem’s refrain of ‘open me’, and in the prologue, which aestheticises the appeal – the magic – of opening a book specifically, seeming to position this book almost as a grimoire. This latter sense is also apparent in the poem ‘Story Time’, in its evocation of the speed and inventiveness of children’s games, their ability to create worlds: ‘We are old now, he says’ – and then they ‘are’. The boy’s bedroom, in this poem, becomes the interior of a ship, and it’s here the story time of the title begins, embedded within a story already created by the boy, ending: ‘He says, This is where / the old man and woman / left their books. // We read them.’ The interesting thing about this poem, and others in the book with the same theme, is that play is not deprecated or merely observed from an adult’s perspective, but taken seriously and participated in.

The first poem, ‘Half Moon Bay’, alerts the reader to St Vincent Welch’s fondness for chiasmus-like repetitions: ‘we waded out / out through . . .’; ‘so many people waded back / waded back / through the bay’. These read as ‘urgings on’ of the poem as it continues, a way for the poem to go on by folding back on itself, something like a cobbler’s stitch, wherein the thread is doubled-back to strengthen the stitch, before continuing. This poem introduces the atmosphere of the semi-magical mentioned earlier. Things happen – ‘we waded out’, ‘I found you singing’ – but the connections between them are permitted to remain vague. The title’s evocation of incompletion, of midpoint, might connect to this poem’s most irresolvable lines:

in the old year’s night in blue violent haze so many people waded back waded back through the bay to me

Who are these people? And why are there so many of them? By these lines a poem that, from its first stanza, a reader might expect to resolve into a lyric commemorating a day at the beach with family or friends, turns strange. Are the people revenants? And is there any relation to the HMVS Cerberus hulk, mentioned in the first stanza, grounded as a breakwater in Half Moon Bay a hundred years ago? This poem exemplifies the double aspect of a number of these poems, on the daily world (‘quiet kitchens’) and a more mystical one, which Melinda Smith in her back-cover blurb describes as the poet’s ability to draw on ‘memory, myth and dream, while remaining tethered to life’s dailiness’.

‘Vasko asks me to play, and so I do . . .’ is influenced, as a note indicates, by the Serbian poet Vasko Popa. It begins:

in line we step now now some out of line long long toe steps some now left behind

Which would go anywhere. It continues:

the wolf puffs, he stills a statue, he checks the sky counts the shadows we shout and totter are chased and eaten we scream and question — what’s for dinner?

From this point – while keeping its pace, even speeding up – the poem moves into a mode of fragmentary impression, the pronouns of the first stanza (he, we) disappear, and it veers into a form of concatenated sound sense, commingling with nursery rhyme:

polished bone raps bone poked skin throw it missile straight toss up hair high high to pick up quick a twelvsie scatter sweep a onesie a twosie dead sheep

Without particularly wanting to challenge the old truism of the personal being political (by placing St Vincent Welch on one side and Garrido Salgado – of whom more shortly – on the other) these poems are personal, their meanings sometimes private ones. Something about the poems evokes for this reader the word ‘cherished’, which is definitely not to make a sly implication that they are over-esteemed by the poet, but rather the word is offered to try to communicate the sense that they feel lived-with, carefully selected, important for the poet, sometimes turned towards a realm of meaning and images that are intimate or private. While it is a reviewer’s cliché to conclude of a first book that it will be ‘interesting to see what the author does next’, in this case it seems justified; being a chapbook, OPEN provides only a glimpse of St Vincent Welch’s work, and yet within that, different directions are suggested, from the experimental to the more conventional.