I first met Sandy Caldow about 30 years ago at Qdos gallery in Lorne, a seaside town in Victoria, where i read poetry for an exhibition. We met up again in Melbourne after she’d left Lorne and moved into a house in Preston – was i in for a surprise! Shifting a worker of clay, like Sandy, into a new studio is a mammoth enterprise – the lift and shift of it is enormous – i pleaded with her to make ‘thimbles’ instead, but she was undeterred. Sandy introduced me to the Art world which i credited her for in my book Heide (2019), an excerpt from this dedication reads:

To overlook, is to fail to notice (or else …

to look down upon). It took me a long time to like Art

or Artists, and to understand the Art around me.

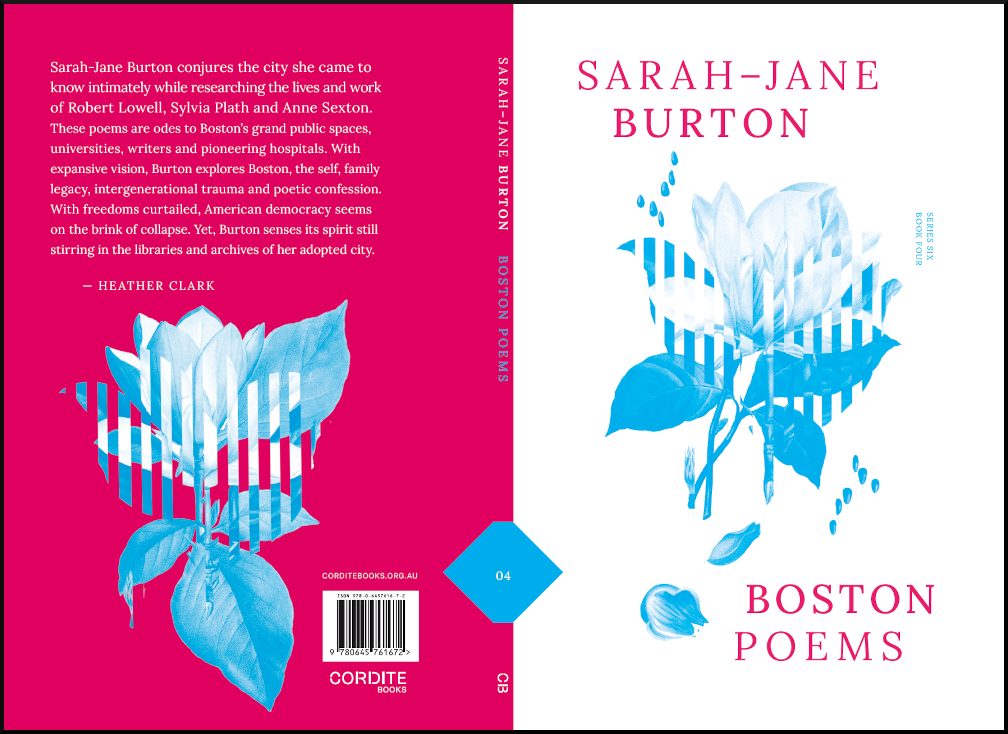

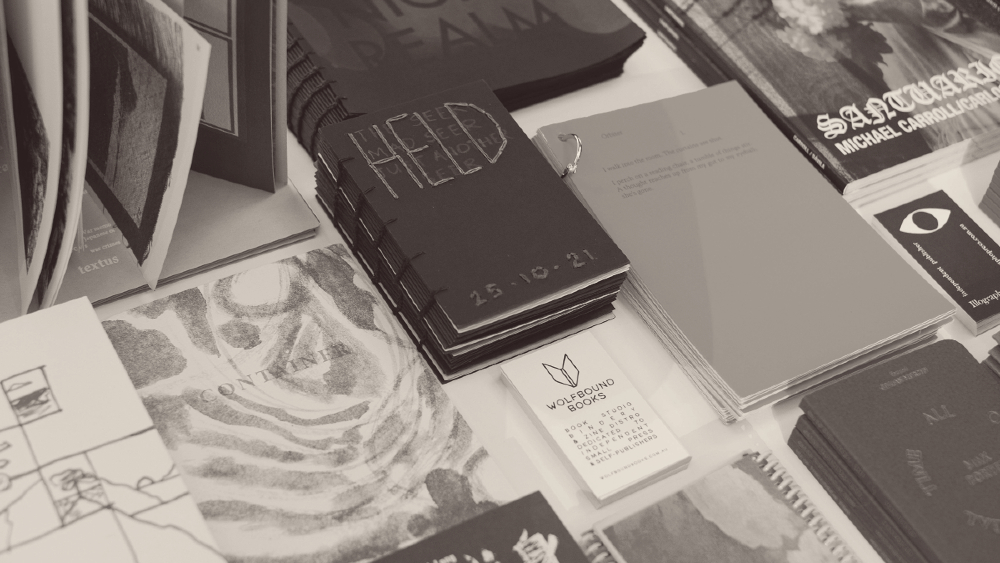

i introduced Sandy, to the Poetry scene. The resulting poetic hybridity is to be found in the art and poetry of her two new books More Than a Face and Watching Words by Collective Effort Press in 2025, brought out defiantly simultaneously.

What attracted me to Sandy’s work was the enormous effort needed to create a poetry that can stare into the very ‘subject’ (via her face sculptures) and fuse the ‘language’ of the poem into a ‘tactile’ form – bringing the sense of ‘touch’ back into the sphere of the metaphysics of the word. As in poetry, when a physical object begins to talk back to you and feed you in its final creation, you know you’re mainlining.

π.ο.: I remember you once saying that ‘a bed of roses explodes at the bottom of the ocean’. Which I’ve always liked, and I think it’s a great place to begin talking about your art and writing.

Sandy Caldow: That was from a time when I was snorkeling a lot, because I’d see the garden underneath the sea and how beautiful it was – the way the waves moved, all of the kelp can be likened to flowers.

π.ο.: Since publishing your books, you’ve had people tell you about how their children love your work. And in many ways Lucy’s Van’s daughter – Rosa – and her connection with your work inspired this interview to happen.

SC: Yes, after hearing from Lucy that her daughter Rosa was asking to be read the poems from More Than a Face – I realised why children could engage with my sculptures. I mean, to them, they are funny faces with different expressions, and the poems go with the faces. Like, the Blue Vase Man (1995), with orange lips and orange eyes. I was quite touched by Rosa’s reaction because she made me look at my art and books in a whole different way. I’d hardly thought about how they appear to a child. Years ago, a friend bought her ten-month-old baby boy to my home. As he was carried through the house he kept pointing and pointing and making funny little baby noises at each sculpture. His parents have one of my sculptures, so we figured that he recognised the style of the art.

π.ο.: You’ve got some amazing stories to share about your sculptures and ceramics, don’t you? Can you give us some more examples?

SC: Well, once a woman showed up my front door with boxes of broken ceramics. Years before I’d made a horse with a human face with a little girl riding it. She told me her husband had fallen off the roof while he was fixing the guttering. He’d fallen backwards off the ladder and onto the sculpture and smashed it into smithereens. The sculpture was about 1.2 meters high by about 1.5 meters long. She believed the sculpture saved her husband’s life because it broke his fall – otherwise he would’ve fallen flat on his back on the bricks below. The woman came to my door with four boxes full of broken pieces and asked me if I could restore it? I hesitatingly said, ‘Well, I can try’. It actually came together nicely, and the horse with its human face looked happy again.

Another interesting story is that a woman came into an art gallery in Lorne three days after an exhibition of my work ended, and wanted to buy one of the pieces, if it was still available. She was devastated to learn the sculpture had sold. It was a very unusual piece – I don’t have a photo of it, but it was a face held up by a strange long neck. The neck had a lot of throwing marks from the wheel when it was made, and the face had strange wafts of green and maroon colors on it. The woman explained that she had wanted to buy this work as it looked like her son who had died in a car accident. The gallery had no address for the person who had purchased the sculpture. So, it was doubly sad because it reminded her so much of her son, and she would’ve been able to have another memory, a ceramic memory of him.

π.ο.: Where did you grow up?

SC: I grew up in Geelong and spent a lot of time on the east coast of Victoria. I used to identify with the sea – walking on the beach, looking at the rocks and snorkeling. From my early twenties and into my thirties I was living in Lorne and working with a master potter there. This was a really important time for me as I was learning the techniques of how to make domestic wear, which involves a strong discipline to learn many specific processes. During that time, I was commissioned by Kosta’s Restaurant to make bowls for them, which was great. Later on, my life suddenly changed – the relationship I was in, ended. I left Lorne and was very sad at that time. Kosta commissioned another series of bowls. When they were complete, I was looking at one of the bowls and realised the colours of the landscape and the ocean were instilled in them. The last stanza of the poem, ‘Kosta’s Bowls’, reads:

I looked at the beautiful view

I saw the bowls in the colors of the ocean,

in the sky, and in the bush

I saw the gold in the setting sun’s

reflection on wet sand

I was happy that the bowls

depicted colors of the sea and bush,

as light changed that day,

in that place,

from moment to moment

Even though I had moved away

two years before,

the colors of the place

were still in my psyche

π.ο.: With all of the levels that these two books cover – ranging from poetry to sculpture to picture books, photography, and biography – it seems like an amazing array. My question is, how long have you been writing?

SC: I’ve been writing and making art for around 40 years. I’ve worked as an art critic for the Geelong Advertiser and for art magazines like Asian Art News and World Sculpture News. I also wrote poetry, diaries, and journals.

π.ο.: What is different about your book of poems compared to other books of poetry?

SC: In the books there are images of sculptures and on the opposite page a single poem probing into the sculpture. They are intrinsically linked and not there as decoration. They are unified. After I make a sculpture I think, ‘Well what am I actually making?’ I sit in my studio and just stare at the piece and write a poem about it. I try to work out what was going on in my own psyche at the time, and what the sculpture was saying about me, or to me. Other poems were written when I heard stories about what had happened to sculptures after they became part of other people’s lives. And that was amazing because some of them had quite dramatic stories.

π.ο.: I think one of the great things about Collective Effort Press, which has been going for about 50-something years, and the people who have been published by it, is that every one of the books is absolutely idiosyncratically individual. Initially you were going to publish your work as one book. But then you said to me, ‘Are we allowed to do it as two books?’ And I thought, ‘Well, in Collective Effort Press, we can do anything we like because the Press doesn’t have to get permission from anybody’. I thought it was courageous for you to bring out two books simultaneously. Why’d you do that?

SC: Originally, I was thinking of making one book, but I realised this work needed to be separated to show two different currents, and for clarity. More Than a Face is about the faces that I make with clay. It begins from when I was a child with the first poem called ‘Mud Pies’. It is based on trying to unearth my own memories when putting my poems together for publication. And then it goes right through my career into adulthood – with different poems and pieces unearthing various memories. Assembling it, was like an archeological dig.

As I child, I remember running inside and saying to my mother, ‘I’m bored, there’s nothing to do’. My mother turned to me and said, ‘Why don’t you go and write a book?’ I was quite surprised by that. But I think subconsciously 40 or 50 years later, these books happened.

π.ο.: The relationship you have between pottery and poetry also involve a lot of themes about death. I mean, you’ve had a few stories like this – like one about the clown faces you’ve made.

SC: A man who was an art collector purchased a clown sculpture from one of my exhibitions. Years later, he tracked me down because he wanted to commission me to make six more. He was elderly and had a terminal illness and wanted to give one to each of his close friends so that he could enjoy seeing their reactions while still alive. So of course, I made them, and I wrote a poem about this man (who survived concentration camps in Europe), and about what I learned from being around him too. I called the poem ‘The Gift’, an excerpt from the poem reads:

He asked me to make him five clowns,

as he wanted to give gifts,

to five special people in his life

Before he died

He wanted to enjoy the giving

And seeing their reactions

π.ο.: Another poem? Another story? Another sculpture?

SC: Another commission I was asked to make, was a very strange one. A woman came into my studio and saw a piece I had made – a bust of a man. She said, is that a bust of a certain man?’ and she named him. And I said, ‘Yes, well spotted’. She said, ‘I’d like to commission you to make ten more for me, just the same as that one’. I asked her, ‘Why?’ And she responded with: ‘Because I hate that bastard and I’d take great pleasure in smashing each piece and then smashing every shard into small pieces’. I didn’t take on that commission.