Grit in the Oyster

Grit in the Oyster

Fitzroy: the biography by Π.O.

Collective Effort Press, 2015

For Π.O., ‘Fitzroy is what you, bump into/ when you leave home’ (599). It was outside his family’s first front door after they escaped the Bonegilla migrant reception centre in 1954. After sixty years and homes in other suburbs, it is still the place that his poems gravitate towards. If anyone were to attempt writing the biography of Melbourne’s first suburb, Π.O. is the poet.

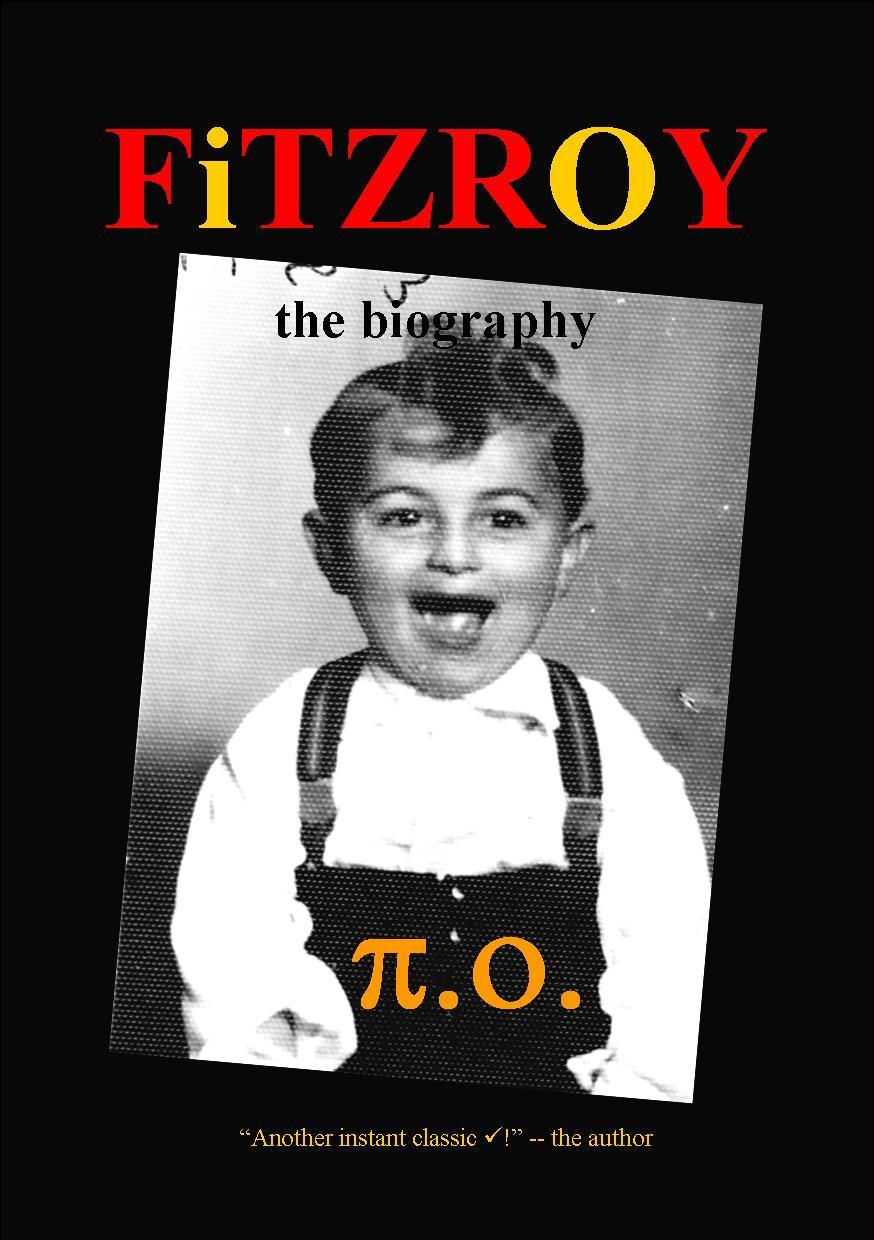

It’d be reasonable to assume that Fitzroy: the biography is about a person rather than a place. On the cover is a photo of Π.O. as a grinning infant, about the age he would have been on first moving to the suburb. The vowels of the title (Fitzroy) are highlighted yellow signalling that the poet, Π.O. (or Pi.O.), is integral to this version of the suburb. The 740-page epic (the same length as his 1996 Fitzroy-based poem, 24 Hours) recounts the life of Π.O.’s Fitzroy. While acknowledging that the suburb has many different selves – is a palimpsest; a space of competing narratives – this study is as much autobiography as biography.

With a contents page arranged alphabetically like a scholarly index, the poem initially appears to be performing as a reference item. Really, it is a catalogue (like Ovid’s Metamorphoses) of the suburb’s changes. Roughly chronological, beginning with a series of portraits and imagined monologues from 19th century settlement and ending with the poet’s own memories, the poem’s scale is vast. In between is a series of ‘creation myths’. We hear how the streets got their names (Young, Webb, George) and the origin of Alcock’s Billiard Table store, on Gertrude Street since 1854 and miraculously still there. We see the Builder’s Arms Hotel, before it was painted white and turned into a restaurant called Moon Under Water. We learn about the Fitzroy childhoods of chocolate millionaire, Macpherson Robertson, and second prime minister of Australia, Alfred Deakin. The advent of footie in Fitzroy, the rise and fall of Squizzy Taylor, the extraordinary role of Pastor Doug Nicholls, and the erection of the council flats (‘Modernism destroyed my whole life’ [607]) are all described with Π.O.’s idiosyncratic specificity, rhythm, and unabashed bias. The same ghostly resonances that were achieved in 24 Hours are present here; the layers of stories convey how contested the space of the suburb is.

In ‘Geoffrey Eggleston (1944–2008)’, Π.O. writes, ‘i wanted to see/ everything, in Melbourne’ (673). As well as wanting to see everything, he appears to want to share with his readers everything he sees. While this is impossible, the mad, kaleidoscopic rush of details gives a sense of infinite completeness. In the fragments, psychic associations and rapid digressions, there is always something new to notice.

Although the structure and scale of Fitzroy: a biography are different to that of its predecessor, 24 Hours, the sensibility behind the poem is recognisable. Even in the imagined monologues of historical figures, and faux archival materials (letters, lists, advertisements, and crime records, which remind me of Charles Reznikoff’s Testimony), there is a latent autobiography. The collaging effect of abruptly juxtaposing miscellaneous facts, and the deliberate (Tarantino-like) anachronisms, stamp the work with Π.O.’s style. Often, the facts that are layered together to create an impression of an historical figure’s life also serve as a commentary on the poet’s writing process. For example, ‘The Latin verb “cogito” (for “to/ think”) etymologically, means “to shake together”./ To smash, to break, to kick down stairs’ (367).

In the later, explicitly autobiographical, poems, there is an openness that is less apparent in the imagined historical monologues, and it is this unmasked storytelling that I think is Π.O.’s forte. From leaving Bonegilla, to being forced to read racist Biggles as a schoolkid, to recalling Allen Ginsberg’s reading at the Town Hall, we see the poet and the suburb of Fitzroy aging in tandem. There are tall stories in which names are dropped (Ted Hughes at the Adelaide Writers’ Festival, whom Π.O. interrogates over Sylvia Plath’s death; Tom Waits, whom Π.O. interrupts while having sex), but also poignant vignettes. At the arrival of ‘students and artists’ in Fitzroy, Π.O.

wrote a poem: Get Out of Fitzroy, and (at night) put copies of it under / their doors; past their Land Rovers parked on the footpath, past their Afghan-dogs and plush-orange carpets; dodging Night watchmen’s torches (in the only suburb i knew) (692).

Throughout the collection is the conviction that ‘the future is just “the past” with a bit of a twist’ (45). These changes that Π.O. witnesses in the suburb in his early twenties have always been happening in Fitzroy’s oldest suburb: ‘“Omne vivum ex ovo” (the complete/ description of the organism, is already/ written, in the egg’ (59). But, despite the inevitability of change, there is a sense of grief in these pages at the corrosive effects of gentrification on Fitzroy. Early in the poem, Π.O. writes, ‘The grit must of course, be in/ the oyster’ (133). In The Age this morning (Saturday 27th February, 2016), an article titled ‘Is this hipster heartland losing its cool?’ laments the addition of a Coles supermarket and Subway franchise to Smith Street. According to Fitzroy: a biography, the suburb started to lose its ‘cool’ decades ago, at the arrival of the first hipsters.

Π.O.’s love of his version of Fitzroy, evident on every page, is palpable in ‘Granite Terrace’, in which he wonders about the granite blocks that were removed from a vacant lot and replaced with ‘some shitty little brown-brick factory’ (78). He suggests that the Council should return the granite blocks and ‘scatter them at random (up and/ down) Gertrude and Nicholson Street, as part of/ some public art project’ (79). If this ever happens, Π.O.’s lines should be engraved in them. Meanwhile, perhaps copies of Fitzroy: a biography could be scattered instead, to remind the Coles- and Subway-goers of their suburb’s origins, to put a bit of grit back in the oyster.