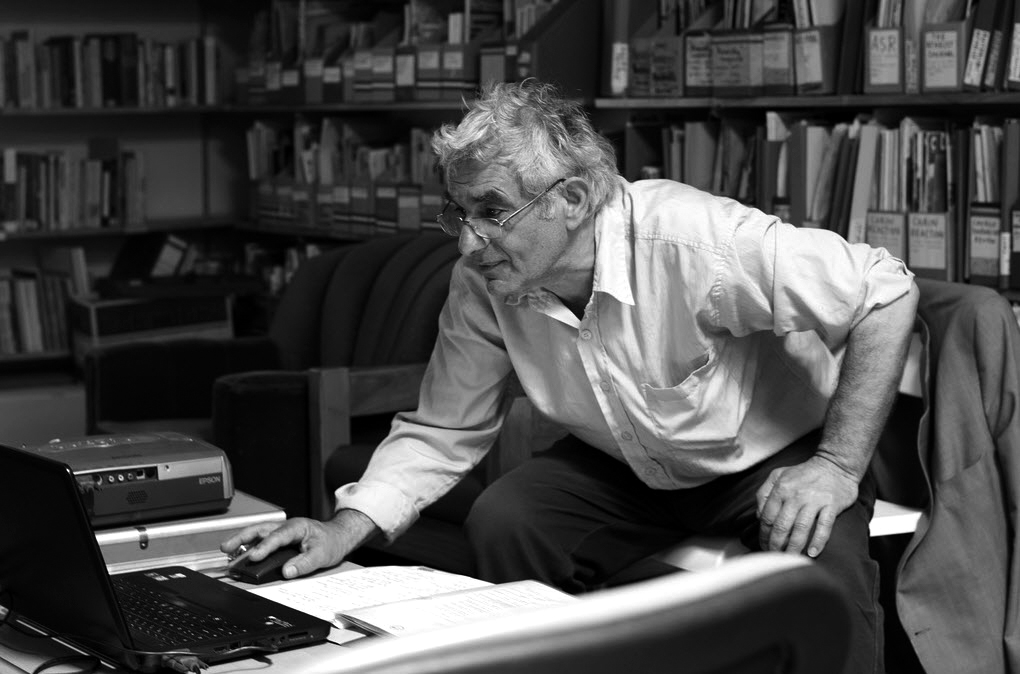

Image courtesy of Paul Rubner

Born in 1951 in Katerini, Greece, ΠO moved to Australia when he was three years old: ‘Went to Bonegilla / migrant reception centre. / Escaped 3 months later. / Raised: Fitzroy. / Reason for living: / Stupidity. / Fuck the spelling.’

This is Π O’s bio note at the end of 24 Hours (1996), a 740-page, self-published epic poem set in Fitzroy, Melbourne. The P and O of his pseudonym are his actual initials and since the 1970s, Π O has been this poet’s stage-name as much as pen-name. In 1977, as Billy Marshall-Stoneking mentions in ‘Π O, An Appreciation’, Π O performed his poetry more than 250 times with Marshall-Stoneking and Eric Beach in and around Melbourne. At this time, he was performing his ‘ego-poems’, a collection of mostly vernacular poetry that publicised Π O as unabashedly ‘fantastic … brilliant … great! (no bullshit)” (Marshall-Stoneking); this demonstrated, or perhaps accumulated, the self-confidence requisite to producing his own contemporary epic.

Π O continues to perform his poetry in Melbourne, with the energy, fluency, wit and talent for mimicry that is not immediately obvious to a reader on first seeing his work in print. ‘Fuck the spelling', in his biographical note, indicates Π O's priorities–voice, aurality, ‘oracy' over conventional literacy. Being faced with: ‘Eye plai (lus' taym) layk “Skool-boi”./ Yes! – But…eye saaaaaaavayv!' (Π O, 1996: 340), is exhausting compared to hearing ‘I play (last time) like ‘School-boy'./ Yes!–But … I survive!' performed in a perfect accent, as annotated above. However, if a reader approaches Π O's written work as a score (a notation that needs to be activated by a reader) or a puzzle that requires the active participation of the reader (which could be said of all successful poetry), the sophistication and humour of Π O's writing becomes evident.

24 Hours, an encyclopedic portrait of Fitzroy in the 1990s, was rejected by six publishers before being published by Collective Effort Press, the members of which are thanked on page 4. On page 2, there is a poetic version of the legal disclaimer (‘All characters in this book / are fictitious. Any resemblance / to anyone living or dead / i consider / a compliment.') and on page 3 a dedication to his sister Athena (‘He's great/ He's fantastic/ I'm brilliant/ I'm his sister'). In a commercially published book, these opening pages wouldn't be remarkable, but, as Π O has complete creative control over 24 Hours–from the quote on page 5 (‘Don't quote me; / That's what you heard / not what / i said. / – Lawrence K Frank') to the type-writer font and layout, author-drawn sketches and symbols throughout, right up to the photograph on the final page of the appendix–all aspects of the book as an artifact appear to influence the poem as an annotation. As his voice, face and gesture would be inextricably linked to the performance of his poetry, so too is the book's appearance important to Π O's written poetry, particularly in the case of 24 Hours.

On the back cover, the closest thing to a blurb, is ‘THE DAY / THE LANGUAGE / STOOD / STILL'. This blurb might suggest that language, once caught on the page, is static and can thus only move and live when spoken. It also suggests the crucial timeframe of the poem. The narrator, Π O (while the poet's isn't automatically the narrative voice, in this case, despite the disclaimer, the voice is definitely Π O's), describes in minute detail a day in Fitzroy, beginning on a mid-morning walk to a café, and ending with the Boss closing his café in the evening. In between, via actual events, flashbacks and digressions, the narrator takes the reader or listener into his haunts and presents him or her with the characters that made up 1980s–1990s Fitzroy: the Boss, his wife and the elderly Greek, Italian, Turkish and Hungarian men who play chess and cards in the café; the boys, Tone and Adam, who deal speed and do ‘jobs' for a gang; the junkies who keep Tone and Adam in business; the women, Julie and Sof, who strip or prostitute themselves for a living; the wandering alcoholics who knew Π O's father back in the 1960s; and the police who frequent Fitzroy, mostly for worse than better. Via a series of socially realistic scenes, vernacular monologues, eavesdropped conversations and imagist observations, the reader or listener is given a thorough, apparently raw and immediate portrait of the poet's suburb.

Cafes! Cafes!, he said: They're tha cause of all the World's problems. All sorts of people go there. All sorts of people! - π.O., 24 Hours, 1996: p 462

Any epic spanning a single day must hark back to James Joyce's Ulysses. As Ulysses is more intelligible when read in conjunction with Homer's Odyssey, so 24 Hours begins to make more sense when its parallels with Ulysses are recognised. There are no stable equivalents for Bloom, Stephen, Buck Mulligan or Molly, but Π O's characters are comparably depicted, with humanity rather than heroism. By examining the similarities shared between 24 Hours and Ulysses in more detail, I will argue for the significance of 24 Hours as a rich, sophisticated contemporary epic poem in its own right.

One Response to Π O’s 24 Hours: Ulysses in Fitzroy