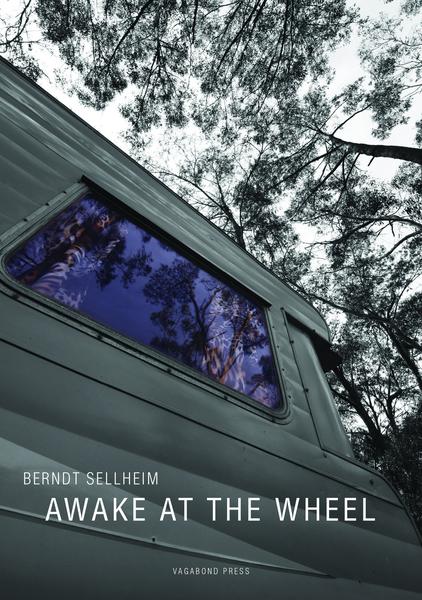

Awake at the Wheel by Berndt Sellheim

Vagabond Press, 2016

In Awake at the Wheel, Berndt Sellheim’s debut collection of poems, Australia is imagined in gothic terms, from the eerie and persistent presence of the ‘bushland’s dark parchment’ to the bones and ghosts which haunt an endless landscape. An homage to country, there is little innocence embedded in these poems of insides and outsides, which speak not only to a transforming sense of self but also to an environment that ceaselessly, and often uneasily, shifts. It is a thematic captured most vividly in the attention to diurnal rhythms – the ‘dying light’, the ‘wash and ebb’ of the sea – which evolve poignantly in relation to the cycles of life and death. In Sellheim’s work, such categories are rarely exclusive, but invested in notions of everyday metamorphosis, such as in ‘The Divine Art of Compost’, in which a ‘lush thermal sweat’ creates a ‘sumptuous / chemistry / of season and decay’. These transformations are ‘all organic matter’, yet there is nonetheless an abiding disquiet, as noted in the suggestion that while there are ‘bodies which build and inhabit’, there are also ‘bodies which lie beneath’, a reminder of how the Australian gothic is interchangeable with the post-colonial.

Such a focus ensures that Sellheim’s poems resist romanticism, and while there are instances of the cliché, especially in the evocation of a Kerouac-inspired ‘road less travelled’, the landscapes (re-)imagined in Awake at the Wheel are problematic, difficult, and often uncomfortable. The beauty of the Australian bush, with its ‘green depths’ which ‘hazewhite past / the eucalypts’, and ‘jacaranda blossoms, like slow, violet hailstones’, is complicated by a history of violence and exploitation, and an insistence on the past as necessary to troubling patriotic visions of nationhood and, indeed, pastoral rapture. Sellheim’s acknowledgement of colonial destruction is nuanced and assured, particularly in those poems focussed on rural Australia, which cannot escape the spectres of past crimes. In ‘Wollombi’, for example: ‘Imagine, Uncle / th black silent feet / passing afore / th whiteblaze wind’.

The politics of Sellheim’s poetry, however, is most striking in its focus on consumerism, and the leaching of the natural world to feed the ever-increasing demand for material goods. Whilst sharp, Sellheim’s poems are more often melancholy than scathing, the collection a despair at the creation of an ‘abject earth’, an overwhelming feeling of depletion and exhaustion. Regional towns are ‘ute-filled borderlands’ while ‘brilliant / machines scrub desert skin’, ransacking for export commodities. The result is a horror-show, an image of monstrosity in which each attempt for more creates only less, until both the land and the individuals who work it are ‘emptied, utterly fucked out by it all’. In ‘Backfill’, Sellheim’s characteristic use of rupture and erasure figures such anxiety in desperate terms:

Great mouth we dug th never-never great mount in dug t dust having gnawed the tin from earth n bones u mountains int ust aving ug the art o bauxite in dug ater from t sun

Environmental fatigue is connected with the dissolution of human life and energy, from the ‘half-forgotten pubs’ overtaken by ‘Big Mac primary coloured / burbs o middle / Australia’, to the rig workers ‘eyebent n crystal meth’. Sellheim is often sardonic in these descriptions – ‘don’t worry […] the drive-through / does bitchin trade’ – keenly aware of the degradation caused by monolithic mining corporations. In an eponymous sequence of poems, for instance, the air is ‘a permanent dusk /o swarming particles /on th scale o Exodus / where all fall short / o the glory o / Rinehart’.

Importantly, in exploring ideas about the loss that comes from over-consumption, Sellheim’s poems are stylistically experimental, increasingly fragmented, and ruptured – verb endings are dropped, letters are missed, and phrases are left incomplete. There is an uncanny use of vernacular that is both familiar and fractured, such as ‘red sky at morn, / she don’t bode well’, and ‘thin edge / o country hedge’. As a result of such techniques, there is a curious tension between what is recognisable – meanings found through obvious guesswork – and a more troubling sense that something remains missing. These gaps are arguably an acknowledgement of the limits of representation, but also a resistance to totality. Poems which begin relatively formally begin to unravel ‘till there’s no place left’ – a suggestion of Sellheim’s preoccupation with the cyclical, but also, perhaps, a refusal to promise completion or even coherence. Indeed, in Awake at the Wheel transformation and loss are perpetually linked, like bodies which ‘bloat and thin and eat themselves / even as we watch’, an abject mimicry of the butterfly, ‘itself a model of rebirth’.