We can see that Burton and Sheperdson engage in a kind of ‘Maya Deren Mathematics’ throughout both UN/SPOOL and A gram of ideas. If the former is an exercise in addition (the overlaying of text onto a wordless film), then the latter, through the process of redaction, is an exercise in subtraction. Yet, from a different vantage point, addition can be subtraction (of wordlessness) and subtraction can be addition (of space). As long as the equations balance, the values themselves are fluid, malleable, infinitely rearrangeable.

And this is where the figure of the ‘anagram’ appears as an overarching principle of artistic composition for Burton and Shepherdson, as much as it was for Deren. Anagrams and equations can be viewed as branches of the same family tree: both are closed systems in which it is possible to rearrange individual elements in multiple ways, with each rearrangement constituting an entirely new iteration, though bounded by the same constraints.

Why is therefore a question that takes us down various rabbit holes to little good effect. As someone with a personality bordering on obsessive-compulsive, and an awareness of the responsibilities of a reviewer, I have spent an inordinate amount of time studiously going down the rabbit holes. Burton and Shepherdson have, after all, clearly identified the source texts for us. But there is no imperative to follow these leads, and to read these poems without having read or seen the texts from which they are sourced is to do so with an uneasy awareness of an unknown underlying code, of a mystery to which one lacks the key. This feeling of unease is not something to be reasoned away but celebrated and cultivated; in poetry, as in all art, comfort and predictability often deaden rather than enrich.

Moreover, undoing knots doesn’t necessarily take you any further along the path to revelation. The answer to the question ‘Why 52?’, for example, is not difficult to find – but to say that Deren’s essay is 52 pages in length both answers the question and leaves it hanging, unanswered, in the space between knowing and understanding. To inquire after meaning, to seek to discern solid lines in place of dotted ones, endings instead of ellipses, is a wire commonly tripped in the reading of art. As we are reminded in UN/SPOOL:

and what does it mean is the wrong question ask who is the portrait how is the brain where does it lead

Burton and Shepherdson have produced puzzles that are as pleasureable to (attempt to) solve as they are to leave unsolved. UN/SPOOL and A gram of ideas are not labyrinths wound around central ‘truths’, but playful works that treat seriously questions of creativity and originality. The final poem in A gram of ideas, ‘52g’, illuminates briefly the figures behind the projectors, giving us an oblique glimpse of the creators in the act of creating (as, of course, they have been all along):

all ourselves such works of disguise reveal the new in marvellous inventions

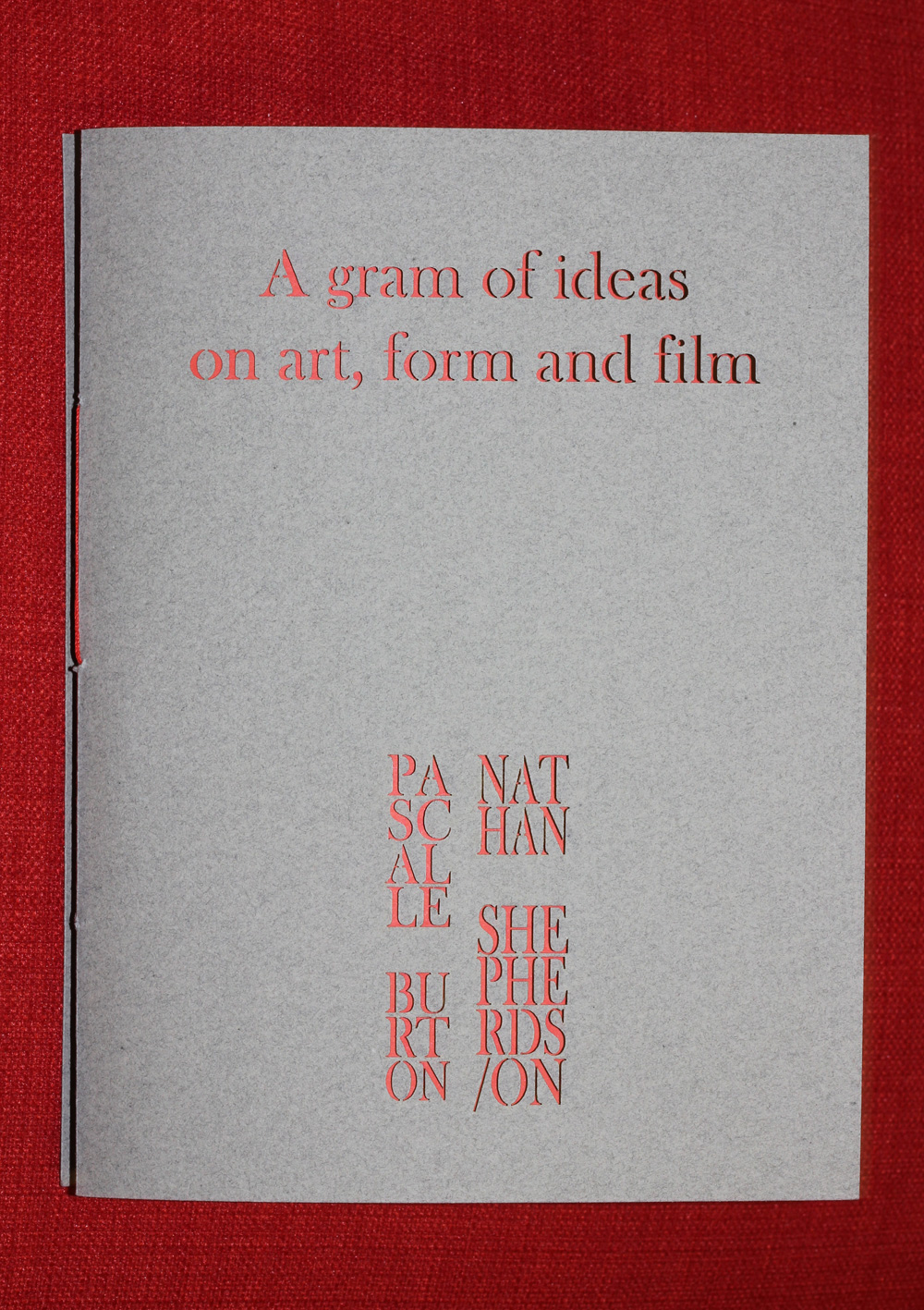

The physical form of UN/SPOOL and A gram of ideas on art, form and film signals an approach to the making of poetry as objet d’art, but this is only the first scene in the complex theatre enacted by these works. It is the close attention to form, in all its manifestations, the studied recombination of old elements to create a whole that did not before exist – the creation, that is, of an entirely new anagram – that make UN/SPOOL and An anagram of ideas on art, form and film fine examples of, and convincing arguments for, Deren’s conception of original and enduring art. Behind the placement of every letter and symbol, the discerning and busy hands of the artists reveal themselves. And by creating the works in complete and dedicated collaboration – in effect creating an anagram of themselves as artists – Burton and Shepherdson have taken Deren beyond Deren herself.

To return to the quote with which we began – and, importantly now – to complete it:

In an anagram all the elements exist in a simultaneous relationship. Consequently, within it, nothing is first and nothing is last; nothing is future and nothing is past; nothing is old and nothing is new… except, perhaps, the anagram itself (Deren, An Anagram of Ideas p. 6).

Pingback: In-conversation with Nathan Shepherdson for ‘axolotl waltz’ book launch | pascalle burton