I would like to acknowledge that this interview took place on the land of the Wurundjeri peoples of the Kulin Nation. May the strength of Indigenous knowledge generously offered by Lionel Fogarty reinforce the place of First Nation elders, past, present, and future.

I would like to acknowledge that this interview took place on the land of the Wurundjeri peoples of the Kulin Nation. May the strength of Indigenous knowledge generously offered by Lionel Fogarty reinforce the place of First Nation elders, past, present, and future.

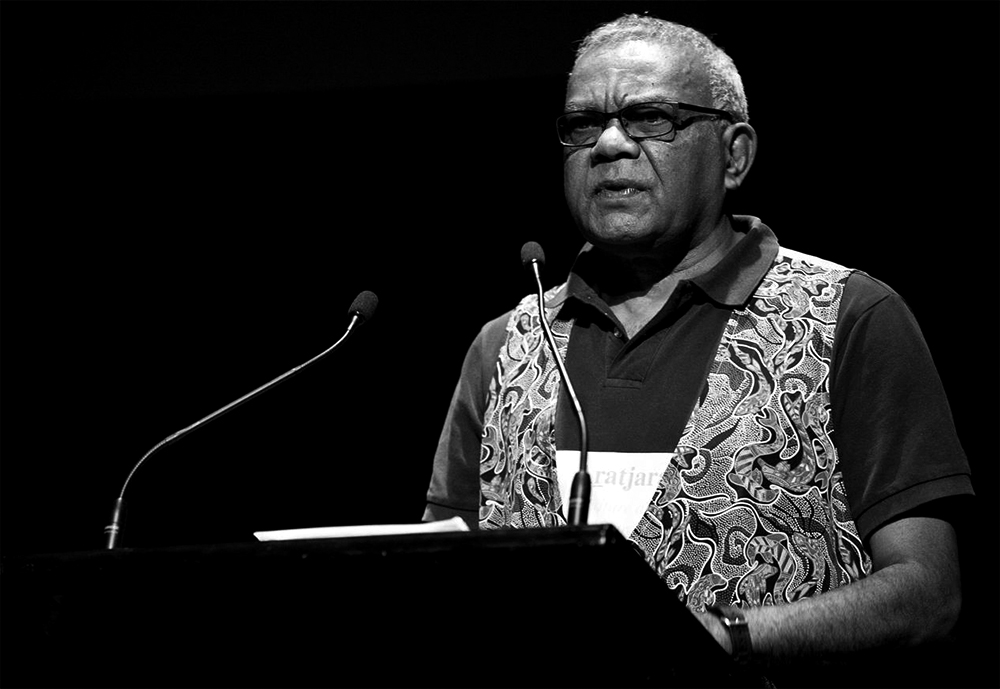

The poetry of Yoogum and Kudjela man, Lionel Fogarty, may be hard to follow, often distorting colloquial phrases or standardised grammar to retool the colonising English language into a form of resistance. His description of it here as ‘double-standard English’ conveys Fogarty’s intent to demonstrate how the English language can oppress Aboriginal peoples, forcing non-Indigenous readers to experience what it feels like to be alienated by a literary text. These actions have led Ali Alizadeh to describe his poetry as an expression of his ‘staunchly decolonised, Aboriginal identity’. I would argue that to read Fogarty is not to be positioned as an outsider, but rather to be given the challenge to conceptualise new reading methods as he positions us in a world estranged from itself.

As is fitting of a self-described ‘oral poet’, a similar experience can be had by engaging Fogarty in conversation. I was fortunate enough to experience this in an interview with him in September 2018. My conversation with Fogarty took place in the lobby of the hotel he was staying at in Melbourne, at a time where I was able to work through some of his manuscript material used for the publication of his most recent poetry collection, Lionel Fogarty Selected Poems 1980-2017. As such, the first question I ask in this interview refers to his practice of illustrating his first draft manuscripts, an aspect of his work which has yet to be properly engaged with in literary studies.

In conversation Fogarty is expansive, often deviating between topics in a rapid stream of consciousness, calling on an extensive memory of names, places, contacts, and inspirations throughout a writing period over forty years. Fogarty’s interweaving of various fragments is hard to follow, yet they leave a collective impression that nevertheless implies his point. To engage Fogarty in conversation, and to ask him questions is also to engage with a series of critical problems. How can we best respond to the philosophical and epistemological foundations underlying these ungrammatical turns of phrase? How might a conversational style inform a written poetics?

Speaking with Fogarty forced me to consider more deeply the intersection of literature with the political biases of those acting within it, as well as the efforts of certain writers and readers to separate the political from the realm of poetry. Fogarty has a unique perspective to offer, for instance, on the ideal relationship between Indigenous and non-Indigenous Australians:

You might think that I’m trying to stop non-Indigenous people from participating in the community, that’s not my motive. My motive is to expose it before it eventuates … co-operating together means co-operating on the basis of what are the real needs, sovereignty, not a heart and compassion change, but a physical material change.

Something I was conscious of in this interview, however, is the extent to which characterisations of Fogarty as an ‘activist poet’ have over-determined the frame by which we read his writing. To this end, I have alluded to a more open conception of his poetics by asking him questions regarding the poetic influences that informed his writing over the course of his career, his experience of being translated, and the poetic connections he has made with other Indigenous peoples of the Pacific.

I am tremendously grateful for the time Fogarty took with me the day we conversed, and for being so patient with my questions. I would also like to thank the editor of Lionel Fogarty Selected Poems 1980-2017, Murri scholar Philip Morrisey, for coordinating my dialogue and to Cordite Poetry Review for agreeing to publish it here. The interview ran for over five hours, with Fogarty barely stopping to eat or drink. Unfailingly, Fogarty was expansive on even a minor point. I have condensed this content here but have retained the key components of what was expressed. Please be advised that this interview took place in a public setting and my transcription of it may include misspellings of some of the finer references Fogarty makes. Fogarty has had the chance to read over the interview, and through a lengthy editorial process, it has evolved into the form it is currently in.

I am still pondering some of the questions Fogarty led me to ask. For instance, is our current conceptualisation of politics in literary studies limited, given what Fogarty expresses far exceeds what may be considered political? Please consider on this note the distinction he makes between ‘land rights’ and ‘earth rights’. How might the extra-literary material found in his manuscripts inform considerations of Fogarty’s existing published texts? Furthermore, how might a renewed valuing of struggle and confusion as critical states better our appreciation of Fogarty’s retooling of the English language? As Fogarty himself says in the interview, quoting from his poem, ‘Tired of Writing’: ‘I see words beyond any acceptable meaning, and this is how I express my Dreaming.’

Dashiell Moore: Thank you for sitting down with me Lionel. What your readers might not be aware of is your practice of illustrating draft manuscripts prior to publication. The way you turn to painting, I’m wondering what is the relationship between when you write as opposed to when you paint?

Lionel Fogarty: Yeah well, my kind of paint, well I call it illustration really, scribbles you might as well say. I call it painting because I paint over it and in-between it, with just normal paint. In terms of their effect, more of illustration I think. Painting or illustrating a police officer, or anything to do with cultural forms, I find that, these bring me into the present-day society for myself because the reflection I had because I was not an illustrator or artist in anyway, but as a speaker, in terms of the poetry I always went into stories. Even if it’s double-standard poetry. I always felt that every verse or illustration of the words has to have a story in it, regardless of every poem that I wrote. In the story I seemed to have fireflies of …

DM: Go ahead, you were on a roll there.

LF: What I was trying to say, is that the fireflies, the fire what happened to me when I was small. My father was the one who taught me how to make the fire, prepare the fire even before I made the fire. I had to go through a couple more years, until seven, before I started to make the fire. I had to gather a lot of chips and things like that. In my younger teens, the fire was a song fire. People sing songs, dancing. But there is no alcohol at that time, or even tobacco. People would just gather to sing songs to more or less welcome other people in and out of Cherbourg as they were shifted around. Painters used to come around my fire. What amazed me, in looking back on that time, the painters used to chuck the paint into the fire when the authorities came up the road. This reflected into me, it stopped me from keeping up that artwork later on when I found out I had a talent in speaking and writing after I became politically involved with the conspiracy charges against the state with Denis Walker and John Garcia. After that, I went into political writing and working with the community creating magazines with Cheryl Buchanan, mother of six of my children. At the time I met her, she was operating down here [Narrm, Melbourne], while I was facing those charges in Brisbane. See I got a long story.

Cheryl was working with the Australian union of students, supported by the Koori Community here, creating the BSB, a Black News service, an information centre, collecting information about the sovereign rights, the Islander fight, everything in Australia at that time. All of this went into the magazine, the union supported get out. Later on, she worked out a trip for me to go up to Aurukun, a festival where they brought tribes together like Garma in Arnhem Land, but before that. I went along to that, Cheryl knew about it and got me to meet the Weipa people who were Mapoon people not far from Weipa, who were taken away from their country from the 1930s and 1940s. I met those people who returned to their country, and at that time, the ABC were doing research on a book on mining communities, involved with trying to abscond the mining out of Mapoon at that time. The Mapoon tried to tell stories to a priest, named Roberts at that time with the research, and they were recording them, letters of course, not political statements about what they wanted. People like Gerry Hudson, Jean Jimmy. I went to the Corroboree ceremony, met the old man, Eric Koo’iola, involved in the Wik decision, way before the Wik decision was happening they went down to Canberra and rallied (Fogarty is referring to the landmark legal case, Wik Peoples v The State of Queensland, in which Native Title Rights was upheld against statutory leases in 1993). Well I met that old man. They got me in touch with a custodian of the area, named Johnny Koowarta (a Winchanam man from Aurukun). He was a traditional owner involved with lawyers and barristers talking to the High Court of Australia. This was way before Mabo. (Koowarta led a group of Traditional Owners to purchase the Archer River cattle station for the Aboriginal Land Fund Commission in 1976, but was blocked by the Queensland Government. Successfully claiming a breach of the racial discrimination act in 1975, Koowarta’s case was upheld in the High Court in May, 1982. Unfortunately, the Queensland state government had gazetted the property as a National Park during this period).