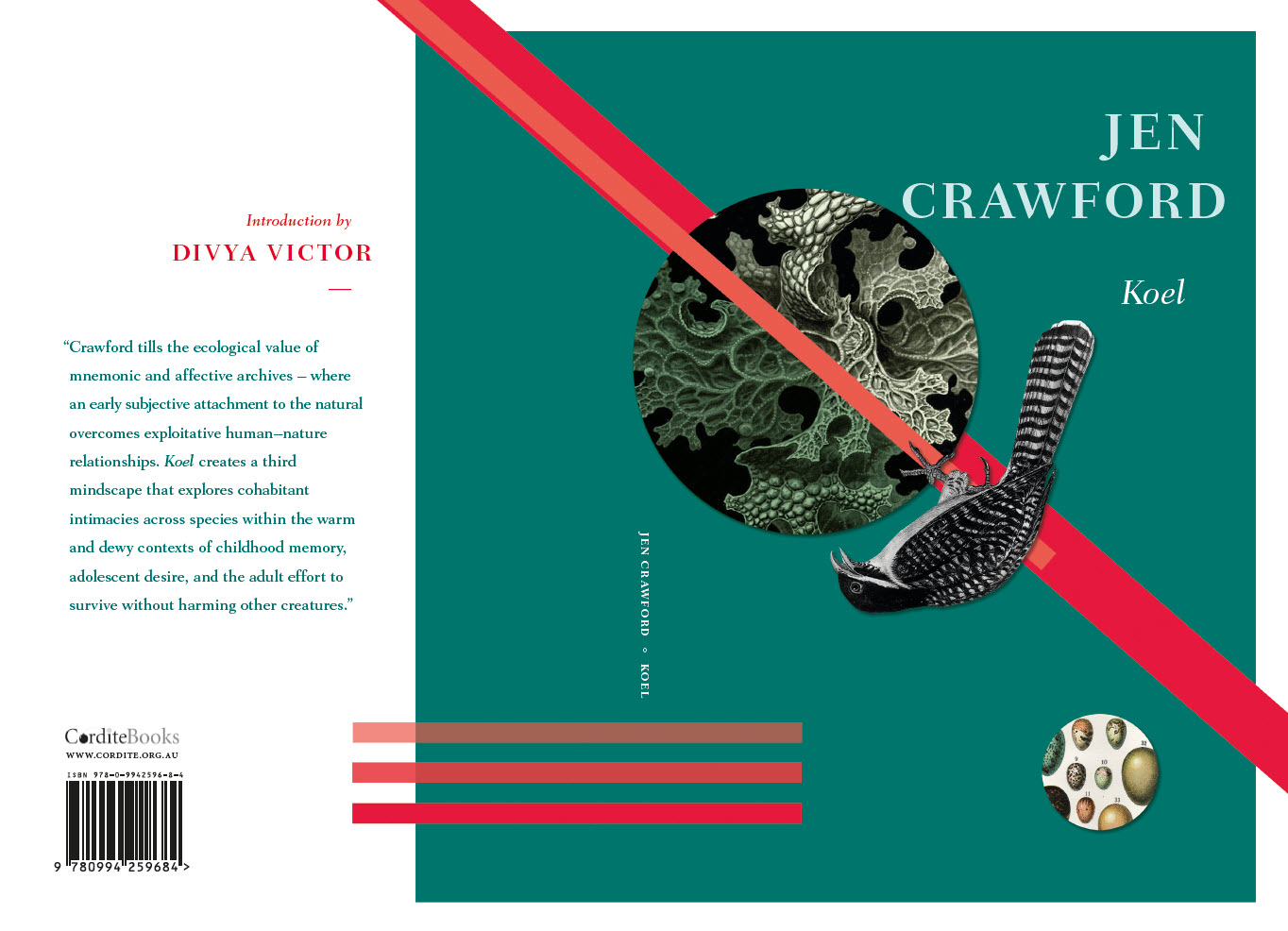

Cover design by Zoë Sadokierski

The koel is called after its call – its name is onomatopoeic, from the Greek ὀνοματοποιία: ‘ὄνομα’ for ‘name’ and ‘ποιέω’ for ‘I make’. The koel becomes itself as it sings out and is heard by a we. We, its human neighbours, find its name by listening to the lilting stretch of two plaintive notes that repeat and ascend in pitch until the whole neighbourhood pulses with its alarm – until the everyday is translated in the carousel call of the koel.

Koel tracks the fecund and chimerical crawl of life – bios – across the topography of New Zealand, Australia, Singapore, the Philippines, and into the warm terracotta of domestic spaces occupied by lovers, mothers and infants. The book offers us a phenomenological terrarium, a lush microcosm of urban and natural life that photosynthesises in the new, synthetic glass globe of late capitalism. Here, human identity grows like tangled filaments; its articulations sprawl like lichen from the cracks between national borders and embrace the cool stones of our foundations. Koel swells with the drama of symbiotic and parasitic life forms, where bodies intermingle and create each other through the hybridities of migrant identity and transnational belonging and are drawn together by the gravity of gravidity.

Mother. Moss. Migrant. These are the lines of consciousness that contour the book. Jen Crawford folds together a transnational atlas of ecopoetic forms. Crawford’s lexicon treks between the scientific, the architectural, and the philosophical, like the U S American poet, Mei- mei Berssenbrugge, tripping boundaries and feralising our cognitive attention. Like Chilean poet Cecilia Vicuña, Crawford reflects on settler-colonial politics, as Koel’s voices take over homes and the dislocation of a ‘self’ – a post-colonial cuckoo driven by dint of geopolitical churn, destroying life in its wake. The poems choreograph a phenomenology of the human as animal, roving between the trans-rational surrealism of tropical wilderness and the hyper-rationality of the biological, inspired by the verdant motifs of modern German dancer, Pina Bausch.

The French horticultural engineer and botanist Gilles Clément has recorded how industrial wastelands can become optimised for bio-diversity, blooming into post-apocalyptic utopias of ‘the third landscape’. Moving like a graceful rhizome between this ‘third landscape’ and an autobiographical one, Crawford tills the ecological value of mnemonic and affective archives – where an early subjective attachment to the natural overcomes exploitive human–nature relationships. Koel creates a third mindscape that explores cohabitant intimacies across species within the warm and dewy contexts of childhood memory, adolescent desire, and the adult effort to survive without harming other creatures.

Koel enacts the saccade of our attention through geographic landscapes and gives an account of how the feminine emerges from what it attends to; through those it tends to. It is the refracted story of how a life grows from a girl rustling among thrush nests in dresses, into a mother with ‘arms knit together as a shroud-knot as an ought / shade,’ and in doing so describes how one life becomes the world for another. Koel is a single day or it is all the days of life moving in grand and feminine interdependence between biological causality and phenomenological existence – between love and violence. Woolf described this place of the feminine when she wrote of Mrs. Dalloway: ‘She sliced like a knife through everything; at the same time was outside, looking on …’ The feminine, running its own attention to the natural world like a high fever, is a visionary memorising the world that is about to break her apart. Each poem in Koel is, in Deleuze and Guattari’s terms, a haecceity – an absolute limit of being entangled in assemblage with ‘an atmosphere, an air, a life.’