OBJECT: Australian Design Centre, Thursday 25 June, 2015

I’m pleased to say that I was at the launch of the very first issue of Cordite Poetry Review, way back in 1997. Good heavens, is that eighteen years ago? The journal is now old enough to vote and to enter pubs unaccompanied by an adult. Back at that 1997 launch at the Bondi Pavilion, Cordite was a broadsheet magazine; really more like a newspaper in appearance. I recall Adrian Wiggins, its co-founder with Peter Minter, spreading a copy against his chest and suggesting that it made an excellent gift – or was it that Cordite might be folded into a T-shirt and worn on special occasions?

Since Cordite went electronic in 2000 it is now much harder to fold into a T-shirt and to wear on special occasions, except in a kind of metaphysical way: the way in which I expect we’re all wearing it tonight. I’ve got mine on just beneath my shirt, and I confess that it’s riding up a bit at the back. Which is what you’d expect Cordite to do, to ride up – or to work or move up from the proper position, as the Macquarie Dictionary would have it.

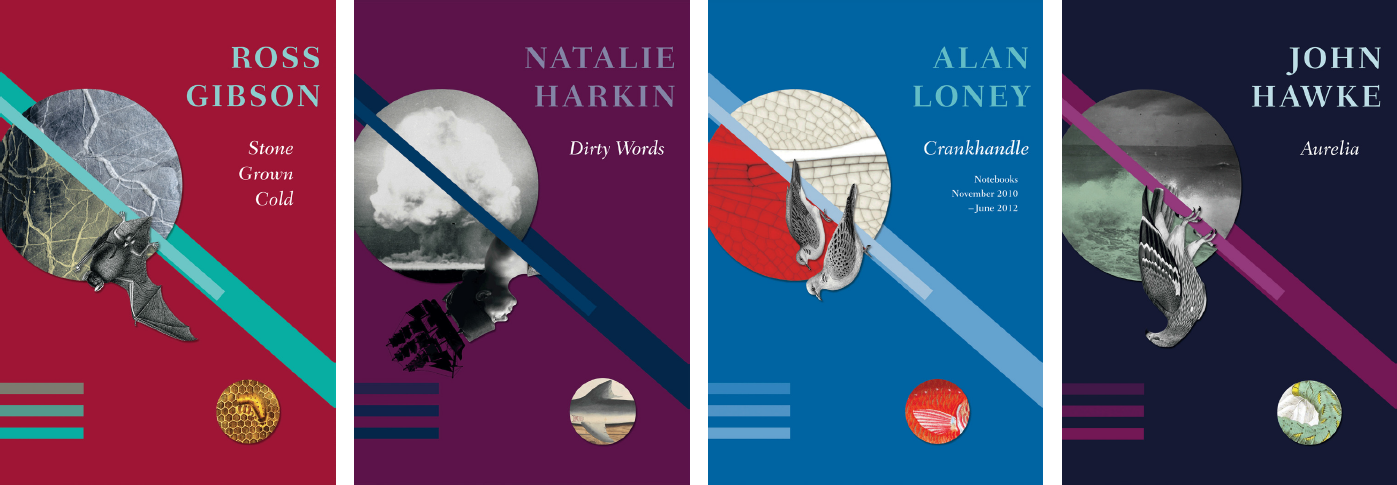

I draw attention to Cordite’s birth on paper in order to note the irony that, after fifteen years online, those who now operate the journal have decided on the bold – some might even say reckless – move to return to hard copy in a new book series. And what a series it is, ladies and gentlemen! Four books: by Natalie Harkin, John Hawke, Ross Gibson and Alan Loney. All trim, taut and terrific volumes, with splendid visual and typographic design by Zoë Sadokierski and Kent MacCarter, respectively. These books effortlessly attain what we ourselves so often struggle but fail to achieve. That is, they are not only beautiful on the inside, they’re beautiful on the outside too. Which is only appropriate, given that we’re in the Australian Design Centre’s Object Gallery. These are gorgeous objects.

But as objects they also contain poetic subjects: variously complex, fractured, partial. Even subjects who are themselves, as Charles Olson would have it, objects – objects within a field of other objects. For these are not books of straightforward lyrical poems, as we understand that often fraught word to mean. The voices in these volumes are sometimes in the process of formation; sometimes in transmission; sometimes in dissolution; and sometimes barely there at all, but rather like ghosts displaced from their former habitation in language.

The most up-front, urgent and insistent of these voices belongs to Dirty Words by Natalie Harkin, a Narungga woman from South Australia. Dirty Words is an alphabetical primer of Australian race politics, a cross-referenced guidebook to Indigenous oppression and liberation. Words like Eugenics, Genocide, Intervention and Xenophobia rub up against others like Justice, Land Rights, Sovereignty and Kumarangk, which is the Ngarrindjeri name for what whitefellas call Hindmarsh Island at the mouth of the Murray River. Many of you will recall the dismal history of the bridge linking it to the mainland, which was approved by the Howard government in 1996 against the wishes of many locals, and in particular a group of Indigenous women. In the manner of payback, Harkin’s project in this book is to make a counter claim: to annex some of the key words of our national political discourse as they affect Aboriginal people, and to hurl them like spear-points against those who presume to rule on their behalf.

A number of the poems have epigraphs from political speeches, such as Tony Abbott’s assertion that ‘Energy consumption defines prosperity’, or Christopher Pyne’s poodle-yapping complaints about the national curriculum’s so-called ‘black armband’ view of history. Under the poem for the letter Y, ‘Yothu Yindi’, the word ‘Treaty’ itself becomes a political dirty word for those who would oppose Reconciliation – but a dirty word that turns into a ‘mantra’, a word of power, for those who take in on board, who own it. Thus the title Dirty Words at one level refers to the weasel words of politicians that Harkin so sharply interrogates. In the process of unpicking the language of power, however, she also implies that ‘dirty words’ may refer to English itself as the language of the coloniser. And in many ways, Harkin’s book is all about how to speak – how to create a forceful subject position – within the discourse of the enemy. The poem for the letter R, ‘Resistance’, is a series of sketch portraits of the aunties in Harkin’s family, each of whom holds clues to her Indigenous identity. The first of these, about Auntie Irene, reflects on ‘that tree where my ancestors/rest that tree standing tall branching out to grow’, and puts paid to our Prime Minister’s absurd claim that to live in a remote community is somehow a ‘lifestyle choice’, like buying a hobby farm.

I’m inclined to think that the phrase ‘much-awaited’ is somewhat overused by reviewers when welcoming a fresh collection from an established poet. After all, a great many established poets publish rather too much already. In her introduction to John Hawke’s Aurelia, however, Gig Ryan very correctly calls it ‘much-awaited’ and a ‘strikingly formidable achievement’. This is Hawke’s first book, I’ve been waiting for it a long time, and it has not disappointed me. Besides being a poet, Hawke is also the author of Australian Literature and the Symbolist Movement, which, along with Philip Mead’s Networked Language, is by far the finest recent critical study of Australian poetry. Not surprisingly, Aurelia adds its own chapter to the Symbolist movement in Australia. ‘The Poet Speaks’ reimagines certain Romantic nineteenth-century tropes about the figure of the poet in anti-Romantic ways, seeming to mock – but in that seeming also to celebrate, perhaps – ‘The one with skin as pale/as powdered parchment, and mouth ripe/as a witch’s kiss’. Furthermore, our hero ‘drag[s] his heavy/feathers in the dust’ in a way that recalls Baudelaire’s albatross.

Though some of the poems in Aurelia are sunlit, this is a deeply nocturnal book. Seas and the night and its stars dominate the mise en scène throughout. In his preface, Hawke cites Gerard de Nerval to the effect that ‘dreams are a second life’; and not only the dreams of sleep, but also ‘the dreams that arise as a consequence of lost desires, dreams perhaps thwarted by chance: of lives once meant but never lived’. These lives play out across the pages of Aurelia. Some of them appear to be from Hawke’s own experience, others are less locatable. But the dominant tone throughout is powerfully elegiac. The book begins with ‘Reliquary’, a wonderful piece of Tasmanian gothic, in which the island state becomes the figurative receptacle or reliquary for the remains its own less than saintly past:

And I’m feeling sorry for all the noise beautiful poems will never contain, because I am ‘modern’ but want to go back for a few words, not many – that’s selfish, but things can seem so desperate you have to act some way, and I don’t believe it’s late.

This is almost an epigram for Australian poetic modernism: its perpetual sense of belatedness, of it being too late; but also the corresponding urge to insist that, no, it’s not late at all, and that beautiful poems can still embrace the ‘noise’ of modernity. That sense of meaning sliding away is there too in the title poem, ‘Aurelia’, where the poet, in good Symboliste style, concludes:

I speak the empty name of this day in the rhetoric of memory, where every word transforms its object into an echo of itself, the lament of endless night.

Christopher Brennan, eat your heart out.

This linguistic slippage of objects into echoes, into mere traces, is behind the melancholy glamour of Hawke’s poems. He’s especially good on things that we must always leave, like rooms and trains – ‘Mountain Train’ is a notable highlight – but also time itself, as something from which we are eternally emerging. When time is transformed into language it becomes history. And so ‘The First Man into Hiroshima’ tells us that: ‘each new thing we build/creates its own pattern, its own constrictions,/which must in turn be discarded./I am speaking of language.’ His words offer a counterpoint to the longest poem in Aurelia, ‘The Conscience of Avimael Guzman’, about the leader of the Maoist Shining Path insurgency in Peru during the 1980s. Whereas the First Man in Hiroshima speaks of discarding the prisonhouses that language makes, Guzman – himself now a prisoner – can’t relinquish his enabling discourse. In that sense he’s like a bad poet:

The magic of cheap rhetoric is retained like a forgotten taste, brushing your tongue. All the things that you can touch refer to secrecy or symbols, but is that magic any more than a good card-hand or a huge library reverberating messages between lines of shelves?

The title of Ross Gibson’s collection, Stone Grown Cold, comes from the poem ‘Barrenjoey’, the headland at Palm Beach on which an elegant sandstone lighthouse sits; and Sydney with its ‘knuckleheaded glamour’ is a major presence in this book. Indeed, Gibson adds a further ‘Five More Bells’ by way of commentary or footnote to Kenneth Slessor’s masterwork, and so we find that:

Beauty gleams for just a moment cinched down as a glimpse before a brewing welt abrades the moon till damp gusts snap the spinnakers and jibs flick and crack.

(Now say that five times repeatedly …) In this wonderfully musical line we very quickly leave the romance languages behind with that cinching or tightening down of beauty’s gleam and start performing a clog dance among all those Old English and Germanic words: welt, gust, snap, jib, and crack.

As lyrical as these lines are, they don’t sing from the traditional sheet music of lyrical poetry. Rather, the compositional method is fractal, as Pam Brown points out in her introduction. The overall impression, across all the pieces in Stone Grown Cold, is irregular, broken up; but close up we detect patterns in the individual increments. Possibly because they exist in fragmentary forms, many of the poems also ache towards narrative, like shattered bones trying to knit.

Gibson’s work on early twentieth-century forensic photographs at the Justice and Police Museum has no doubt been influential here. In his Accident Music online project between 2009 and 2013, selections of these images were linked with short improvisatory three-line texts that Gibson called ‘mutant haikus’. Hints and glimpses of a potential story, mere flashes, were given to you, but you had to make up the rest yourself – and what a strange and uncanny experience that could be. Though it is more profoundly minimalist, the long sequence in this book called ‘Incident Reports’ reads just a little like Gibson’s 2008 novel, The Summer Exercises, which also came out of the forensic photos. A quasi-narrative poem that deals more explicitly with crime, ‘Chalk Sees Light and Dark’ contains the extraordinary sentence ‘And he’d be primed to hit the road soon in an air-conned diesel four-runner that he could filch quick from its hiding-spot near the Mongrel Mob’s country meth-lab at the back of Smut Root’s old sheep-run down in Kangaroo Valley’. Australian English never seemed more like a foreign language: the language of Mad Max: Fury Road, perhaps. And on the subject of cars …