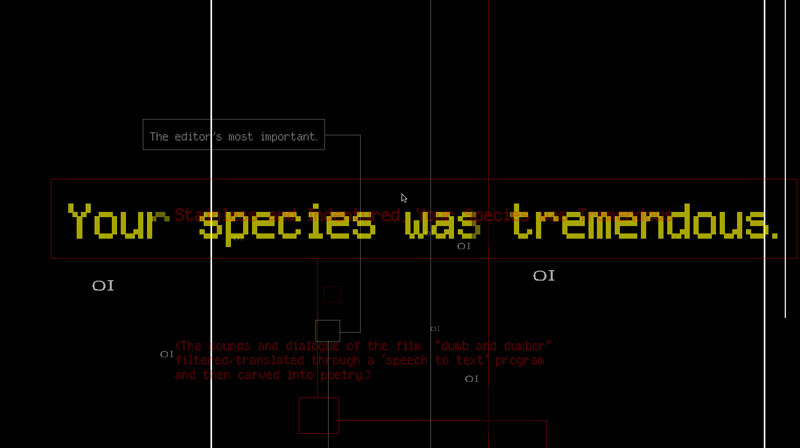

Image: screenshot from Jason Nelson’s Depth: Text and Playthings.

Cordite 36: Electronica has been a fascinating and challenging issue to put together. It contains forty new poems, fifteen spoken word tracks, a dozen features and, for the first time, a selection of multimedia or ‘e-lit’ works. Bringing together these disparate types of content raises an interesting question for Cordite as an online journal. Have we finally broken through that invisible barrier between ‘text-based journal’ and ‘online journal of electronic literature’?

In her editorial introducing the issue, Jill Jones rightly points to the issue’s presumptive focus on electronica and electronic music, specifically “the ways musicians in various modes and guises have used electric technologies to generate sound.” The poetry in this issue runs the gamut from highly experimental works to extended meditations on musical memories and forms. It’s absorbing, intriguing and puzzling – and this is just as it should be.

The spoken word tracks selected by our audio editor Emilie Zoey Baker are similarly pre-occupied with the bleeps, hisses and clicks we associate nowadays with electronic music. From Philip Norton’s bizarro Yes I Dream of Electric Sheep to Sean M. Whelan and Isnod’s Dream Machines, the works selected here paint an aural kaleidoscope that fizzes and pops, echoing electronic art from the works of Phillip K. Dick through to Kraftwerk. Check out the individual tracks or stream the hour-plus mix of electronica as one. Headphones highly recommended!

When it comes to the selected works of multimedia or ‘electronic literature’, however, we are faced with a series of disruptions that more often than not question rather than reflect the theme of the issue. Benjamin Laird’s Sound-less-scape and nothing left in, for example, present the reader (viewer? player?) with opportunities for interaction but remain stubbornly mute, like a silent rave. Joshua Mei Ling Dubrau’s Et Tu demonstrates the jump-cut nature of screen-capture technology when applied to text, while Konrad McCarthy’s TV Life strips bare the artifice of the audio-visual in a montage of movements.

The publication of these pieces – some HTML-based, others video – inevitably raises the question of genre and form. Is this literature? Is it even e-literature? As Tim Wrights asks in his review of the Electronic Literature Collection Volume 2, ‘What literature today isn’t electronic?’ I’d like to think, instead, of overlapping spaces – some of which may be electronic, others organic. Beverliey Braune’s Supra-text Sequences essay offers one glimpse into such a world.

When it comes to the work of Jason Nelson, one might instead ask where the electronic world actually stops. I’m really excited to be able to publish three of Jason’s work in this issue, because in many respects his work attempts to break through the imposition imposed by the computer screen to offer a neural landscape that is deeply textured and interactive. Depth: Text and Playthings addresses this tension directly, by stating bluntly ‘Your screen is horribly flat’.

Image: screenshot from Konrad McCarthy’s ‘TV Life’.

Elsewhere, Nelson’s work is playful and self-referential. Branching: branch branch is a work where the traditional branching structure of file folders clashes comically with a goofy soundtrack that is perhaps more amenable to a 1980s computer game. Meanwhile, With love, from a failed planet presents a phantasmagoria of late-capitalist logos. In addition to these pieces, I’m pleased to present an interview with Jason in which he reflects on his creative practices as an electronic literature artist.

Nelson’s work offers one possible ‘entry-point’ into the world of e-lit. The work of Mez Breeze offers another. Sally Evans’ essay entitled ‘The Anti-Logos Weapon’: Excesses of Meaning and Subjectivity in Mezangelle Poetry demonstrates that electronic literature can be just as much about ‘texts’ as traditional literature. Mez’s work is justifiably renowned in e-lit circles as innovative and highly complex. In an online world where more and more of us are exposed to the vagaries of computer code, Mezangelle chews up that code, parses it with human language and spits out art. Adam Fieled’s essay on Gertrude Stein’s Tender Buttons (a work that is itself highly amenable to remediation as a hypertext) shows that the worlds of literary practise and literary criticism remain inextricably entwined.

In terms of my own personal experience of electronic literature, Mez’s work was amongst the first that I viewed (scanned? played?). Over the course of this year, working as a post-doctoral researcher on the ELMCIP project, I’ve also met a wide range of scholars and practitioners working in the field of e-lit. For this reason, I’ve included in this issue two interviews with my colleagues at Blekinge Tekniska Högskola in Karlskrona, Sweden. Both Talan Memmott and Maria Engberg have inspired me to re-think my attitudes to the digital realm.

This brings me back to the question of Cordite’s place within that realm. As Benjamin Laird demonstrates in his overview entitled Australian Literary Journals: Virtual and social, Cordite is by no means alone in its attempts to engage with online communities. In fact, pretty much every Australian literature journal is undergoing a process of morphing and reinvention. I’d like to think that, in the future, Cordite will evolve to include more works of electronic literature that actually engage with the medium in which the journal ‘lives’.

This is not to suggest that the thousand-odd poems we have published on the site over the past decade are not ‘alive’, or that text-based works are somehow inferior to HTML, Flash-based or interactive works. Nevertheless, I hope that these tiny steps we have taken towards the electr(on)ification of Cordite will inspire others to create engaging, accessible art that takes advantage of the multitude of possibilities made available when viewing (reading? parsing?) information using a networked computer.