Image from Consejo Nacional del Libro y la Lectura

Image from Consejo Nacional del Libro y la Lectura

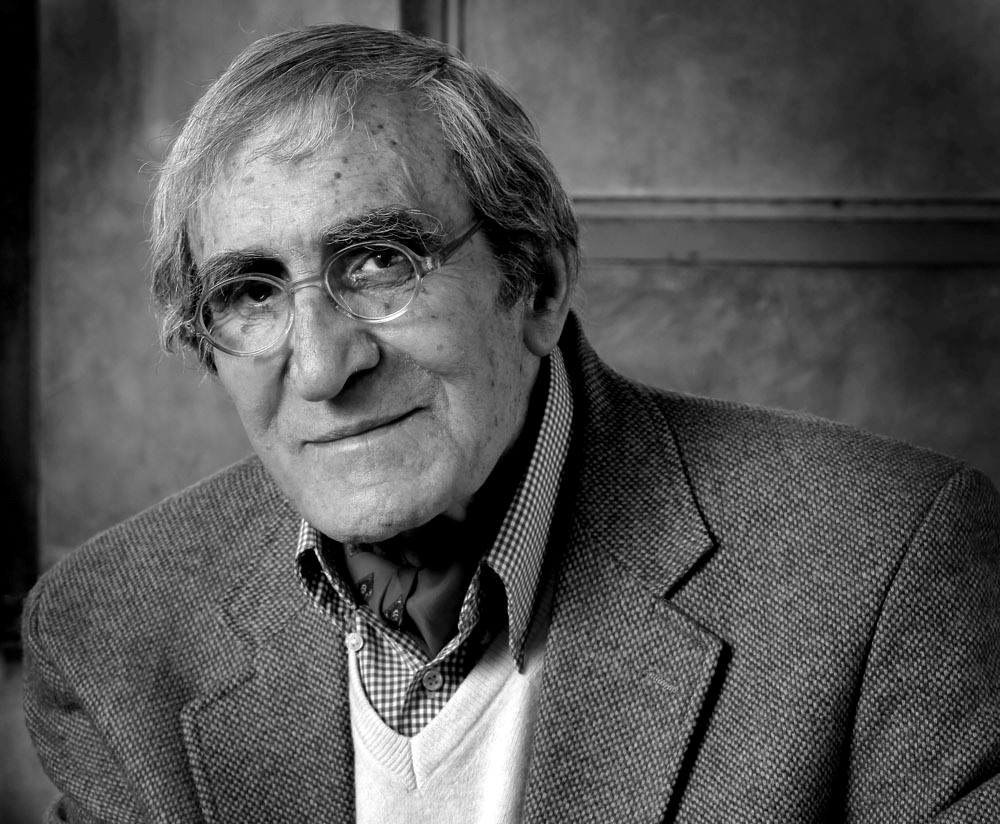

Ennio Moltedo Ghio (1931–2012) lived all his life in the cities of Valparaiso and Viña del Mar, Chile. His friend, Allan Brown, says that poets like Moltedo may well be known as a porteñistas; people who have as their main literary ‘conversation’ focused on the cultural beauty of Valparaiso. This city was the main port in the Americas prior to the construction of the Panama Canal. The first boats coming to Australia from England stopped here.

Ennio Moltedo, a descendant of Italian immigrants, was born in Viña del Mar and worked in Valparaiso all his life, traveling between the two – this and other experiences relating to these cities, their cultural matrix, and the sea as biologic matrix, emerge to the fore in his poetry.

The cultural history of the region manifests in its railway stations, plazas, the port, houses and avenues … and the poet’s displacement through this urban space manifests in the beauty of place – the border between development and sea, dictatorship, the dismantling of the patrimonial city under siege by neoliberal and free-market policies which brought about the corruption of its character.

Moltedo published a number of poetry books during his life: Cuidadores [Caretakers], 1959; Nunca [Never], 1962; Concreto azul [Blue Concrete], 1967; Mi tiempo [My Time], 1980; Playa de invierno [Winter’s Beach], 1985; Día a día [Day to Day], 1990; La noche [The Night], 1999 and Las cosas nuevas [The New Things], 2011. He also, very early in his life, collaborated with Pablo Neruda on translation from the Romanian into Spanish of a selection of poems titled 44 poetas rumanos [44 Romanian Poets], 1967. A Postumous book of Moltedo’s chronicles, La línea azul [The blue line] is forthcoming by Altazor Ediciones in mid 2013.

Moltedo published regularly until the Augusto Pinochet dictatorship changed everything and, as a consequence, there is a break from 1967 until 1980 – a time Moltedo spent replenishing strength and honing articulation of the violent change at all levels of social reality. His best known work is his late collection La noche [The Night] (1999) which contains a poem of the same name included here.

This selection of poems – translations into English has been done by Israel Holas-Allimant, Sergio Holas and Steve Brock – is part of a larger translation project that also includes Moltedo translations from Spanish into Italian and French.

Óptica Todo va montado en este par de anteojos, Viejo parabrisa polar, ampliador justo y misterioso: allá vienen, anchas alas sobre el mar, escondidos entre dobleces, con cañones –nadie sabe lo cómo lo hacen- , los cincuenta y tres mil hombres de la flota del dragón.

Optic Everything is mounted on this pair of spectacles, old polar windscreen, just and mysterious amplifier: there they come, wide wings over the sea, hidden between folds, with canons –nobody knows how they do it – fifty three thousand men of the dragon fleet. (From Cuidadores [Caretakers], 1959)

Nunca El niño pasa por prados lejanos y demoraría vidas esperar su arribo que se entretiene. Canta, salta y se moja en el agua desconocida de los animales. Penetra las tinieblas con preciosa bolsa y sonríe al junco que lo desliza seguro por la huella de pies grandes. Y como no conoce mercados ni luces enfermas, no visita las fiestas prisioneras de los pueblos. Las madres prometen largos juegos cuando él llegue. Los hombres trepan, buscan, tallan alta silla, y se piensa en un ramo, en una vela retorcida al calor, todo para un brindis futuro que asegure que esa cortina será la gracia de la calle. ¿Y el escudo? Ése ya está ocupado por el señor y la dama de colores. Los hijos solitarios han elevado un mirador. Arriba, con sus primeros peinados, escudriñan con gestos y juegan el mismo racimo. Excitados por lo que suponen ya cerca, con gritos reclaman a los atrasados que corren portando sus ruedas y cañas. Pero el niño pasea por prados lejanos y demoraría vidas esperar su arribo que se entretiene.

Never The boy passes through distant fields and it would take a lifetime to await his arrival, entertained as he is. He sings, jumps and bathes in the unknown water of the animals. He penetrates the darkness with his precious bag and smiles at the boat that safely slides him along the track of big footprints. And since he knows nothing of markets nor sickly lights, he doesn’t visit the prison-like parties of the people. The mothers promise long games for his arrival. Men climb, search, carve tall chairs, and think about a bouquet, a candle twisted by the heat, everything for a future toast ensuring this veil will be the grace of the street. And the coat of arms? That is already occupied by the gentleman and the dame of colours. The solitary children have built a lookout. Above, with their first hairdos, they scrutinize with gestures and play the same game. Excited by what they know is coming, with shouts they call up those late ones that run carrying their wheels and canes. But the boy passes through distant fields and it would take a lifetime to await his arrival, entertained as he is. (From Nunca [Never], 1962.

Frente al mar A Hugo Zambelli Frente al mar he visto cosas poco comunes; por ejemplo, en pleno invierno, un alcatraz gigante, parado en medio de la playa, solo, y con los brazos cruzados sobre el pecho. Al acercarnos, el pájaro nos dio la espalda y comenzó a correr por la playa desierta; primero lentamente, con dificultad, luego más rápido, hasta alivianar su peso con las alas; hasta elevarse con gracia y perderse en el cielo.

Facing the Sea To Hugo Zambelli Facing the sea I’ve seen some uncommon things: for instance, at the height of winter, a giant pelican, standing in the middle of the beach, alone, with arms crossed. As we got closer, the bird turned its back on us and started to run across the deserted beach; first, slowly, with difficulty, then faster, until lessening its weight with its wings; until graciously lifting and losing itself in the sky. (From Concreto azul [Blue Concrete], 1967)