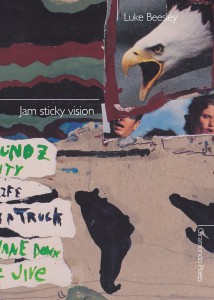

Jam Sticky Vision by Luke Beesley

Giramondo Publishing, 2015

Luke Beesley’s long-term preoccupations with film, visual art, writing and literature, return to the fore in Jam Sticky Vision, with the poet now expanding the scope of his work to include 90’s alt-rock bands, like Silver Jews and Pavement. With allusions to filmmaker David Lynch and lo-fi rock musician Bill Callahan couched unselfconsciously beside poems about James Joyce or Henri Matisse, Beesley’s poems may seem to be drawn from something of an eclectic palette. What links the poems nicely together, though, is a close examination of the here and now. In the epigraph from John Dos Passos’s essay ‘The Writer as Technician’ (1935) this idea is more precisely expressed as ‘a time of confusion and rapid change like the present, when terms are continually turning inside out and the names of things hardly keep their meaning from day to day’.

The first poem in the collection, ‘A Thousand Characters’, for example, evokes an image of the setting sun over a rugby paddock: ‘It’s getting dark remarkably quickly and the clouds, just above the line of trees which form the horizon, here, are salmon-pink’ (1). But the image is unstable, fleeting. As the field of ‘freshly cut lawn’ morphs, the poem almost twists itself inside out, we see ‘Nature as documentary, now’, the field becomes a sound stage or movie theatre, a disco, a zoo or some amalgam of all and none – reality quivers on its support beams. This how the poem ends:

See the magpie on the end of my sandwich? It knew it was to be written, probably, and it curved here like a ball in a stadium. But there is no crowd, bird, alone in the credits. Some gaffers. Giraffes with appalling foot rot trot over to the microphone and discoball concussions the wild shining toffee of the dance floor on this afternoon as the moon pierces in. (1)

Thinking about Luke Beesley’s poetry perhaps requires some understanding of his writing process, since the poems themselves often engage with the difficult business of creativity, or the ‘square task of art’, as Beesley terms it (‘A Tusk’s Chalking Innocence Against Evening’, 60). In Beesley’s work it seems true that how he writes – i.e. his technique, routine, tools, etc. – informs and is in itself a meaningful aspect of what he writes. Collated from pencil-sketched drafts of quick-writing, his poems have a way of seeming to enter the world at an angle, coming in crosswise; they gesture broadly in the direction of reality, which is always a moving target. Reading Jam Sticky Vision produces a sort of house-of-mirrors effect, in which the sensory world is reflected back at the reader in its full vibrancy but, simultaneously, returning distended, canted a little to the side: ‘I had a cup of coffee in a small cup, and time asleep was a dream hidden’ (‘How Will I Know When I’m Home?’, 71). Stylistically his work pays particular homage to the New York School poets, like John Ashbery, Frank O’Hara, and Kenneth Koch – in fact, Beesley’s poem ‘The Australian Double’ receives its title from a line in John Ashbery’s collection Quick Question (Ecco Press, 2012) and the poem ‘Coda’ references Koch in its opening: ‘So I wait here reading Koch drinking in the morning checking the spelling’ (54). Certainly, Luke Beesley isn’t shy about telling you whom he likes, and the references and allusions to these influences are made with genuine affection, without a drip of Bloomian anxiety.

In this way pleasure is central to Jam Sticky Vision – sensory pleasure as much as aesthetic, perhaps prompting Tim Grey in his launch speech to describe Beesley as ‘an erotic poet’. In the hilarious poem ‘The Master’, Beesley chews over a single image, repeating it over and over, recalling Gertrude Stein, or perhaps more poignantly, Astrid Lorange’s analysis of pattern and repetition in How Reading is Written: A Brief Index to Gertrude Stein (Wesleyan University Press, 2014). As he inverts the words in the image Beesley appears to be trying to taste their meaning, spreading the image out so it reaches every one of his taste buds. The line ‘Cabbages & the sea’ repeats, almost like a mantra, then reforms as ‘The colour of cabbages & the sea’, which inverts to ‘Colour of sea & then the colour of cabbages’, and eventually becomes the full-formed image of the ‘colour of aftershave & the majority of blue skies on cloudless / Cabbage coloured days & the sea infused beaches & / Cabbage coloured uniforms & the sea’ (17-19). Though there’s nothing remotely ‘erotic’ about the image itself, Beesley’s preoccupation with it, the way he turns it around and looks at from every angle, does resemble a kind of sensory obsession with words, which is almost a kind of fetishisation. Words in Beesley’s poetry have physical and sensory properties; they’re there to be held between your forefinger and thumb, fiddled with, flicked from your plate or put in your mouth:

Cut page dessert knife salsa at the hour of lunch like pepper pressed tightly in a casual walk, buckled, under the questions. The waitress accommodated against potato, his acumen and silky argument ‘admired’, he claimed, his knife and for fucking the day harlequin geometrics at the trailing tie. (‘Nude Descending a Solo’, 12)

Throughout the collection, and particularly in the excellent closing suite, ‘How Will I Know When I’m Home?’ (61-72), the excessive energy of the absurd is witnessed creeping its tendrils into the less colourful, though no less meaningful, ordinary world of bedrooms, train stations, and kitchen sinks. In this last poem, written during Beesley’s residency at the Wheeler Centre, Jam Sticky Vision’s compounding of images arrive at their most intimate and vibrant timbre, seeming to suggest that, in the immediate reality of our present times, the absurd and the day-to-day are not in competition, but wholly one and the same: ‘There was no leaving the house. The house was there. It wasn’t immobile, wholly, but an address beyond pencils and creamy duck-feathered coloured paper’ (63).

Even though so many of its cultural debts are American (n.b. the bald eagle seen swooping in from the top-right corner of the cover image) Jam Sticky Vision still feels like a distinctly Melburnian collection – stylish, witty, erudite, contemporary, but also personal and close to what one might call home. Ultimately, the collection offers readers a visually rich spread of poetry, comprising a hyperreal blend of ekphrasis, absurdist imagery, anecdote, and autobiography, which somehow manages to be as entertaining as it is challenging and profound. Reviewing it has been a joy.