Subtraction by Fiona Hile

Vagabond Press, 2018

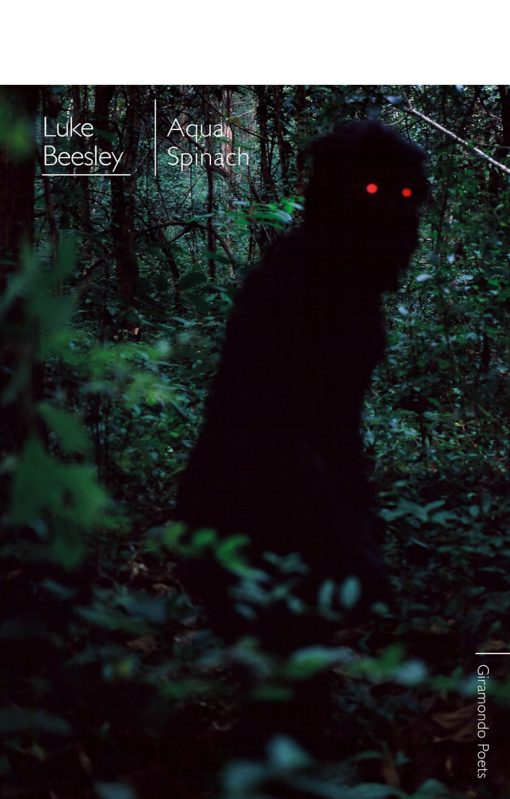

Aqua Spinach by Luke Beesley

Giramondo, 2018

Two very recent books by two mid-career Melbourne poets offer distinct intellectual gymnasiums in which to lift and push and run and sweat. I may not have been able to master these books, but they knocked the breath out of me.

Fiona Hile’s second collection, Subtraction is not poetry for the uninitiated. It is sophisticated and, honestly, inscrutable. In an interview with Sandra D’Urso, Hile saysid she sometimes makesde poems by stripping down chapters of a novel-in-progress. And, indeed, the poems do read as something like the opposite of story. Could it be this process of radical redaction (subtraction) to which the title, at least partially, refers?

It could be said tThe poems reject narrative and lyric conventions: the conventions of establishing context, positioning speakers or agents, and crystallising experiences. However, they feel instead as if they are generated in a world quite apart from such considerations. And I must talk about the ‘feel’ of these poems, because, at least at first, I was slipping off their surface like a novice climber on a slick slope. I admit, I did at some early point think: I don’t think I can review this book – not because I didn’t like it, but because I couldn’t understand it. However, unwilling to abort the mission, and more and more disinvested in the notion of expertise and mastery besides, I kept on. Those readers who managed higher than a B in their post-grad continental philosophy coursework may have an easier or more satisfying time intuiting the poems’ implicit philosophical preoccupations, but I must meet them on the level of affect and feeling.

And how do these poems feel? They are gloomy. They vibrate with dissatisfaction. They joke. They bite. They are baroque and insatiable. They torrent. They hold themselves in utter balance.

I want to say something about how the lines work. Staying mostly faithful to the syntax of the sentence, the poems pile vivid arrows of declarations and questions and conjoined imageries upon each other, and they all point in different directions. The poem ‘Aubade’ features a ‘bedside colander’, a ‘hatful of hollows’, ‘Two handfuls of sunrise’, ‘a fake hostage video’, screams, love, money, and choice – and that’s only the first quintet.

At times the poems display something like a warped Whitmanian impulse to radical inclusion: quadruple-visioned, and buzzing with the tension of opposites. The poem ‘Song for an Indifferent Italian,’ ends thus: ‘A wall of windows irrigated / by flights of sluggish moths, whirring in the chest of the / Moreton Bay Fig. An electrified bolt splitting the carapace, / plastic flowers strewing the dashboard, longish knuckles / ructioning the parquetry, the top half of a terrace / with its affordable glimpse of the harbour, her collection of nice / looking but impractically small suitcases’. At times the poems display something like a warped Whitmanian impulse to radical inclusion: quadruple-visioned, and buzzing with the tension of opposites.

How are these poems made, then? Why these choices? Why this particular almost-overflow of taut, utterly specific, yet seemingly unanchored private thought-cogs? What does this machine do?! The poems are embedded with clues as to how to read them. One poem asks, as I do:

What is Form and Why is this happening?

The later lines suggest a slant answer: ‘the poem is a container for the formless horror of your eyes as emotion … representation of the poem as a container for the formless.’ However, these lines are not fair or typical examples of Hile’s brilliant wordplay. Better to cite a line like: ‘The curlicue scent has not the mother in it.’ Just, wow. Or her reappropriation of sistine as a verb, as in: ‘I thought I saw you sistine through / the overstimulated waters of our local / swimming pool.’ See what I mean about her being funny? She is funny.

One penetrable theme of Subtraction is a continuum between love, domesticity, womanhood, and compromise. ‘My Views’ is one of the poems that announces itself as an intensive emotional self-portrait, and could be read in light of female experiences of domestic self-erasure. The poem ends with a quotation from Theodor Adorno’s Aesthetic Theory: ‘Something frightening lurks in the song of birds’. What Adorno goes on to say, which Hile does not quote, is:The rest of the quotation reads, ‘… precisely because it is not a song but obeys the spell in which it is enmeshed.’ Women’s submission to the definitions of the male imagination, ideas of shape-shifting and being constrained, and the questioning of one’s own existence (‘Did you ever have a name? / It’s lost … You were designed to reflect’) preoccupy the collection’s later poems.

So, this is how I have steeped my brain in this collection. I now sense that these poems are not only inscrutable – not merely inscrutable – to the reader, but also to themselves. By which I mean, these are poems both somehow engorged and starving, starving for answers, and yet replete with their own restlessness, their own unanswerability. This is an amazing book.

Luke Beesley’s third collection Aqua Spinach is similarly restless, and similarly challenging. Although the character and feeling of Beesley’s work is distinct from Hile’s, both of these difficult, anti-lyric collections challenge the reader to disrupt her mind’s habitual grasping for logic, narrative, and cohesion. Further, both books are self-consciously intertextual. The poets employ allusion and use opaque strategies of collage as engines of composition. Hile’s influences and allusions may be more seamlessly folded into the fabric of the poems. However, she, too is liable to name-drop. Euclid, Jean Racine, and Kierkegaard (referred to, with causal intimacy, as K.) appear alongside Dolly Parton and Mr Softy, the American ice cream truck mascot. Both books claim access to and make use of the consolations and repulsions of both high and low culture.