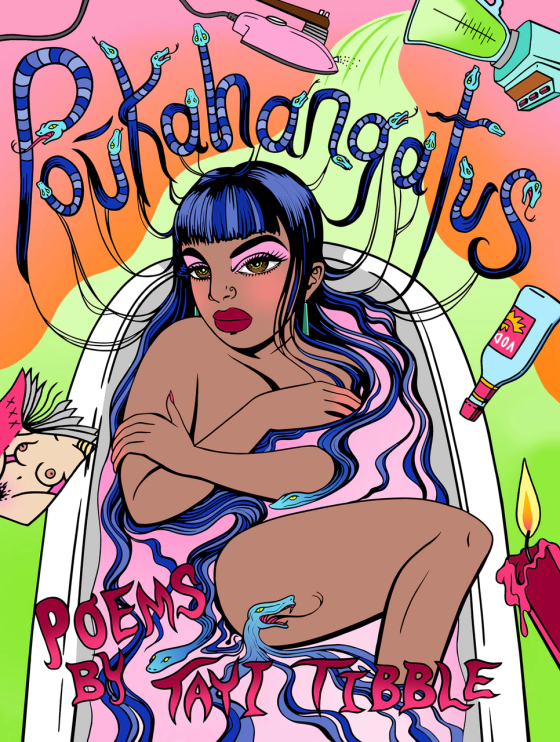

Pokūahangatus by Tayi Tibble

Victoria University Press, 2018

Against the Whiteness of settler-colonial Aotearoa history, Tayi Tibble brings from margin to centre, her Indigenous experience as a Te Whānau ā Apanui / Ngāti Porou woman. Pokūahangatus is her debut poetry collection, which explores the violence of settler-colonialism against the imagery of pop culture, Māori activism and the strength and sensuality of Brown women. As Tongan, Palangi (Palagi) and Samoan poet Karlo Mila wrote in her PhD thesis, ‘Polycultural Capital and the Pasifika Second Generation: Negotiating Identities in Diasporic Spaces’, Tibble’s poetry reveals how ‘culture, ethnicity and identity signal the complexities of lived experience[s]’ for Indigenous and Pasifika folk. Pokūahangatus chronicles the struggles of being Māori and woman in a colonised land. By sharing this lived experience, Tibble aims to write beyond and despite marginalising stereotypes that deeply affect herself and her communities. Her work reveals authentic and creative representations of what it means to be a strong young Māori woman.

As a mixed Tongan-Australian woman from Mount Druitt, Western Sydney, born the same year as Tibble (1995), I resonate deeply with her poetry. Pokūahangatus is a fictional, hybridised Māori word paying tribute to Pocahontas of the Powhatan tribe. The title itself is poetry allowing for broader discussions of cross-Indigenous solidarity. A chance to understand each other. Therefore, it is no coincidence that the opening poem, ‘Pokūahangatus: An Essay about Indigenous Hair Dos and Don’ts’ begins with oral storytelling:

[G]reat-grandmother on her bed, cutting the thick peppery plait falling down her back with a blunt pair of orange-handled scissors. Remember the resistance. Imagine if the ropes of Māui had snapped and the world had been plunged back into the womb of darkness.

By speaking the whakapapa – the genealogy of Māori ancestry – as the opening for her collection, Tibble reshapes and reclaims her colonised land.

It is then that the Māori women flood in and rightly take up space. The poem, ‘In the 1960s an Influx of Māori Women’, outlines the intimate domestic experiences of young Indigenous women who wear ‘printed mini dresses’, buy ‘vodka and dirty magazines’, who get their hair fixed straight at ‘Lambton Quay’ and ‘[t]hink about drowning themselves in the bathtub’ only to ‘[r]esurface with clean skin’ then ‘rinse and repeat.’ Tibble’s poetry shows the complex lives of Māori women who struggle with and resist the tools of colonial power such as fashion, print culture and alcohol. Their rising up with clean skin is an act of constant resistance, an act of sovereignty. It is the intricate politics woven into Tibble’s collection, which gives her writing strength and purpose.

But what does it mean to grow up Indigenous in the twenty-first century? For Tibble, growing up Māori in this day and age means navigating difficult family relations, understanding the allure of sex and dating, and feeling the whakamā – the shame and the aroha – the love. Her poem ‘Scabbing’ encapsulates all these experiences with phresh images, vernacular and tone. The narrator remembers regretting breaking up with her twelvie ex-boyfriend who, ‘makes $50 scabbing schoolkids for a dollar’ and to ‘make matters worse he’s a proper rugby player now’. The shame involved of having broken up with a Brown man, a ‘true hustler’, leads the narrator to lament about the life they could’ve had together as she beats out all the Bogan beauty queens of the Greater Wellington Region to become a proper ‘Kiwi socialite’. The love involved within Indigenous domesticity becomes paramount, where the narrator fantasises of being a Brown man’s housewife and fucking together until they both die. Even in all its irony, there is something powerful and sovereign in two Brown people hustling together until death.

However, while it may be overlooked because it centers on the pop culture franchise Twilight, the most significant poem in the collection is ‘Vampires versus Werewolves’. I was around fourteen when the first Twilight film hit cinemas. Well, hit my TV on a burnt CD my aunty had bought back from Tonga’s illegal DVD shop. I remember staying up until 3am playing the movie on repeat and murmuring along with a grainy Edward Cullen, ‘And so the lion fell in love with the lamb’. Then, I’d stand in the shower and scrub my brown skin with ALDI soap and wear long sleeved skivvys to hide from the sun so that I could look as White as Bella Swan. White enough so that someone like Edward could love me. Growing up, my nickname was Fie Palangi, which means Wanting to be White. I remember stomping around my kui fefine’s house in Mounty County, beating the soles of my Chucks on her freshly mopped wooden floorboards proclaiming to my hundred aunties and uncles who were over for a feed, ‘I’ll never ever marry a crazy coconut!’ All my fam laughed it up at me. Then, I ran to hide in the darkest part of my grandmother’s lounge room and under a statue of White Jesus I began to recite the entire dialogue of Twilight from memory.

What Tibble is actually writing about in ‘Vampires versus Werewolves’ is the experience of wanting to be White coupled with the experience of coming to critical consciousness as an Indigenous woman. The poem is complex because it is in the form of dialogue, which is shown by an italicised secondary voice who, from the left margin, repeatedly asks: ‘Could you be more specific? ’ This forces the narrator to continuously build on Twilight as a metonym for White supremacy on the right margin. Tibble writes, ‘Brown reminds me of leaves and sausage roll wrappers in the gutters’; an image of self-hatred. Later, she writes, ‘All you want is that pale sparkling on the television’, building on images where her self-hatred originated from. By using the phenomenon of Twilight, Tibble reveals how our White supremacist society leads many young marginalised people of colour to obsessively destroy themselves to Whiteness. As young Brown women, there is nothing we wanted more than to leave the gutter and become White; hoping that one of our own ‘wolf pack’ boys would take us home to their parents instead of the palangi girls, while we pinned Edward Cullen to our bedroom walls. Same sis. Same.