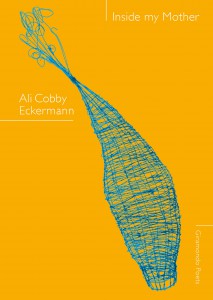

Inside My Mother by Ali Cobby Eckermann

Giramondo Publishing, 2015

Celebrated South Australian writer Ali Cobby Eckermann’s fourth volume of poetry, Inside My Mother, is her most substantial and diverse collection to date. Although the book includes a handful of reworked earlier pieces, most of the seventy-three poems are new. Across four sections, these poems enrich and intensify the politically urgent subject matter that Cobby Eckermann’s oeuvre has, over the past decade or so, addressed so effectively. As an Aboriginal descended from the Yankunytjatjara language group, Cobby Eckermann’s chief concern is to express what she sees as the untold truth of Aboriginal people, both in terms of vital aspects of their culture, as well as regarding the (ongoing) detrimental impact of European colonisation. In this new work, Cobby Eckermann’s personal story provides a strong substructure in relation to which these larger issues are artfully explored.

One of the major strengths of the volume is the skill with which Cobby Eckermann employs a varying array of personas, voices and styles to convey her material. With respect to the autobiographical pieces, it is largely through first person lyrical verse and third person narrative that we learn of her struggle for identity, and its resolution in her (re)connection to her Aboriginal birth family (adopted out under questionable circumstances, she was raised to adulthood by a white family). Overall, the notion of family is a key motif, and cycling through the work is what this idea means in Aboriginal spirituality: family is a broad but vital network involving both the living and the dead, and, importantly, their interrelatedness with the environment. Thus, in ‘Tjukurrpa’, Cobby Eckermann writes: ‘my father is the sand dune / that rock is my mother’. The book’s title poem, a high point, illustrates this interrelatedness with a potent image of her mother’s death:

my mother the dying throws sand in her face, tasting the grit in her mouth and wailing louder throws herself forward, pushing her breasts into the softness of the earth, her mother … and I walk away leaving her there in that cradle, safely nestled in the roots of that tree, safe in her country our solace her grave

The maternal, a much-debated Western concept since the emergence of feminism, is approached quite differently here: the theme of mother opens out to a set of challenging, non-European inflections that multiply its possibilities.

In the same way, elements of the natural world are transformed in these poems: sun, moon, sky, birds, trees, sand, water, shells (and more) appear again and again, in various states, almost as characters playing as central a part as the human figures. There is a constant sense of movement between and within these elements, a circulation that calls to mind Stuart Cooke’s linkage of contemporary Aboriginal poetry to the poetics of traditional Aboriginal songpoetry. The songpoem, as Cooke notes, is an ‘assemblage of various human and nonhuman actors’, and, in the telling, ‘the emphasis on any particular subjectivity recedes amid multiple subjectivities’ (91-92). Such a dispersal of priority also occurs in relation to time. Amongst the poems, past and present experiences intermingle: a poem set in the present in an Aboriginal city camp, for example, in the voice of an Aboriginal man (the highly aural ‘Marry Up’), sits alongside one concerning a young girl, set forty odd years ago in an Aboriginal mission (‘The Letter’). Likewise, a contemporary lyric in which Cobby Eckermann expresses her communion with animal life (‘Heartbeat’ – ‘boobook owls permeate / their call transmutes me’) leads into a narrative set in a time prior to Western impact (‘Innermost’, wherein a woman mourns her husband killed on a hunt). Such placements are both affectively resonant in their abuttal, and perform the cultural belief that the past, especially as a spiritual modality, remains very much alive in the present.

Cobby Eckermann has said that Aboriginal writing is necessarily political, and this collection is openly so in its drawing attention to Australia’s historical maltreatment of Aboriginals, and to the social injustices that abound today. Poems mourn, lament, protest, and rage against a host of violations, and some, such as ‘Unearth’, constitute a metaphorical call to arms:

let’s dig up the soil and excavate the past breathe life into the bodies of our ancestors … the sound of rising warriors echo … there is blood on the truth

Several poems point to the importance of the survival of Aboriginal languages (language is another variation of mother). Not only is poetic impact heightened by the scattering of Aboriginal language words and the periodic pidgin English voice, but these function to subvert the dominance of English. The poetry is in the main rhythmically strong which, together with frequent repetitions, achieves – again – a songlike quality. I contend too (cautiously, given my ‘white’ consciousness) that an Aboriginal sensibility is detectable at a syntactic level. The lack of punctuation connotes an informality, and the many poems made of spare couplets or tercets invite a measured reading, allowing for reverberation and silence. This overlaps with the Aboriginal way of listening to one another and to the land, as expressed in ‘Kulila’:

sit down sorry camp might be one week might be long long time … sit down here real quiet way

It is evident here, and in structural decisions more generally, that Cobby Eckermann is adept at matching form and content.

There are, however, a few syntactical blemishes that stand in contrast. Occasionally, there is awkward phrasing or a diction that jars; this tends to occur in more abstract or complex passages. A few such pieces are rather overloaded and here, less would be more (as in “Kaleidoscope”). But working at the linguistic crossroads of two cultures – in English but from an Aboriginal perspective – Cobby Eckermann is perhaps entitled to the odd entanglement. Had I more room, I would go on to detail more of the collection’s powerful imagery (Cobby Eckermann’s training as a visual artist is palpable). As a final comment, though, it must be said that this volume continues to advance the significance of Cobby Eckermann’s writing in the context not only of Australian, but also world, literature. Its poetic achievements are considerable, and the ethico-political value of a text such as this is immense. What remains, as the collection itself frets over, is the challenge of integrating the thrust of this work into our social reality.

Works cited

Cooke, Stuart. ‘From Songpoetry to Contemporary Aboriginal Poetry.’ A Companion to Australian Aboriginal Literature. Ed. Belinda Wheeler. Rochester, NY: Camden House, 2013.