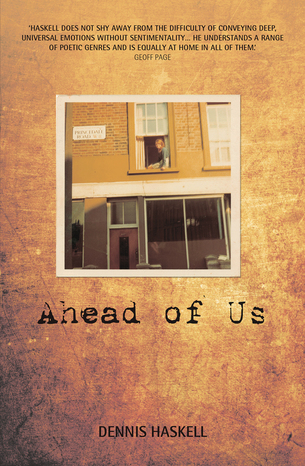

Ahead of Us by Dennis Haskell

Fremantle Press, 2016

‘Her absence is like the sky, spread over everything,’ wrote C. S. Lewis in a work of prose, published soon after his wife died. Under such conditions poets are apt to explore their grief by way of lyricism, and, while it is uncommon in the Australian context, recent years have seen several international male poets producing collections in just these circumstances. From the United Kingdom, for instance, we have Douglas Dunn’s Elegies and Christopher Reid’s A Scattering, and, from the United States, Donald Hall’s Without. In fact, each of these writers lost his wife to cancer – a misfortune also experienced by distinguished West Australian poet Dennis Haskell in 2012. Haskell joins this particular elegiac community with his eighth volume of poetry, Ahead of Us. This work, which gives insight into Haskell’s relationship with his wife, her illness and death, and his striving to endure in the aftermath, certainly offers moments of resonance with its further afield counterparts. But Haskell’s ordeal of mourning is, of course, uniquely his own, as is his poetic, and the two combined have resulted in an affecting sequence of distinctive and finely wrought verse.

The collection is structured in three parts, the first of which is ‘Chance.’ While revealing aspects of Haskell’s life before his wife became ill, these poems (many selected from earlier publications) also deal with such metaphysical agitations as time’s intransigency and the indifference of nature (or chance, or ‘god’) to human design. There are broad variances in tone (from melancholy to light-heartedness), but a skillful deployment of circulating images, as well as double negative and oxymoronic phrasing, sustains a sense of personal and existential unease: the section’s narrative pull spirals slowly through a series of ghosting oppositions – light/dark, thinking/feeling, presence/absence, earth/sky, and so on. This vacillation is reminiscent of Tennyson’s modus operandi in his long elegy In Memoriam, and Haskell occasionally accords with Tennyson in arriving at a point of stability: in human love (‘one call from my son/… and all the small mundane world/and everything it holds/… suddenly sings’), and in meaning-making (‘each attempt/at meaning is an act/of defiance of death’). On the whole, though, an unremitting ontological silence engulfs any promise of calm. The word itself appears again and again: silence is ‘long,’ ‘complete,’ ‘recurrent,’ ‘deafening,’ and, in the title poem (which closes part one), silence is the framework out of which loaded freight trains call us ‘into the determined dark.’

Elsewhere in the collection, Haskell describes silence as ‘utterly ordinary,’ and this points to the significance of ‘the ordinary’ in his poetry. In one poem he champions ordinary suburbanites over ‘intellectuals [who] spread contempt’ (this dig at Patrick White and Barry Humphries is remindful of Helen Garner’s essay ‘Suburbia’), and his subject matter is often the minutiae of everyday life (‘Get washing sorted, the dishes/stacked, the ironing board out,/ …’). When, in part two, we enter ‘That Other Country’ (evoking Susan Sontag’s ‘kingdom of the sick,’ which requires a separate passport), cancer is described vernacularly as ‘The Big C,’ with ‘chemo’ as its remedy. The use of vernacular diction and ordinary occurrences may, in a cursory reading, give the impression of aesthetic under-development; this is not the case. Haskell is on record as valuing ‘direct simplicity’ in poetry, and he agrees with Pound that ‘only emotion endures.’ His exercise of the ordinary here – in language, in his depictions of life, in his often-conversational tone – is one way he effects emotional sincerity, by which he strives to engage the ‘common reader.’

More generally, it is through considerable poetic expertise that Haskell attains affective impact: rhyme variation, rhythmic movement, deft control of line length, and delicate fashioning of imagery all weave a visceral discourse of lamentation. Some of these techniques are evident in ‘After Chemo’: ‘In each corner of each room,/swirled across the tiles,/I find them, these networks,/these fine cobwebs of you;/they’re flowering down your clothes:/every jumper, every skirt,/even your socks are/laced with these filaments,/hair like slender moths,/like will-o’-the-wisp,/these fine threads of you/drifting away.’ Similarly, ‘Renewal,’ which tells of his wife choosing only a short-term renewal of her driver’s license, reveals great artistry: ‘and something funny/folds up/inside me/and keeps trembling/its flimsy, papery breath.’

Typically, the complex of emotive responses involved in the grieving process includes anger, and, in part two when ‘the dictatorship of death’ comes into view, the tone sometimes approaches indignation. Interestingly, at these moments cancer and death are gendered as male, with Haskell depicting an adversarial relationship between himself/his wife and the disease. While accepting the autobiographical nature of these poems, it must be acknowledged that, as rhetorical posturing, this characterisation may fail to connect with some (especially cancer-associated) readers: much cancer literature is moving away from metaphorical frameworks suggestive of combat. For my own part, my experience with spousal cancer neither found me imagining cancer/death as masculine, nor perceiving the events in terms of a competition.

This is a minor qualm, and as part two continues, the portentous momentum accumulates. Two-thirds in, when we come to the long poem ‘Saturday Night and Sunday Morning,’ we reach the text’s nadir: its still centre. In numbered segments, and in carefully measured pacing, this piece narrates the sequence of events that ends with literal death. As the reader journeys with Haskell through his wife’s final hours, stylistic matters lose import: the reader becomes a silent partner, fully participating in the intense feeling that suffuses the scene. Part two’s remaining poems extend this highly personalised mood, as they detail the material and emotional terrain Haskell traverses in the following months. Several compelling pilgrimage pieces, wherein Haskell returns to locations he and his wife once visited, reverberate subtly with Thomas Hardy’s ‘Emma poems,’ written for his own late wife.

The final section, ‘Fascination,’ comprises only one poem, addressed to Haskell’s new grandchild. Here the tone lifts, leading us to consider whether this fresh vitality indicates a late pathway to solace. If we were to read the collection as one long elegy, could we take this as a traditionalist transformation of grief into consolation? On balance, no. The uplift of this one poem does not overturn the impression of a poet deep in mourning, and, still shaded by ‘the dark aftermath of death,’ the reader is left duly discomfited by the propinquity of love and grief.