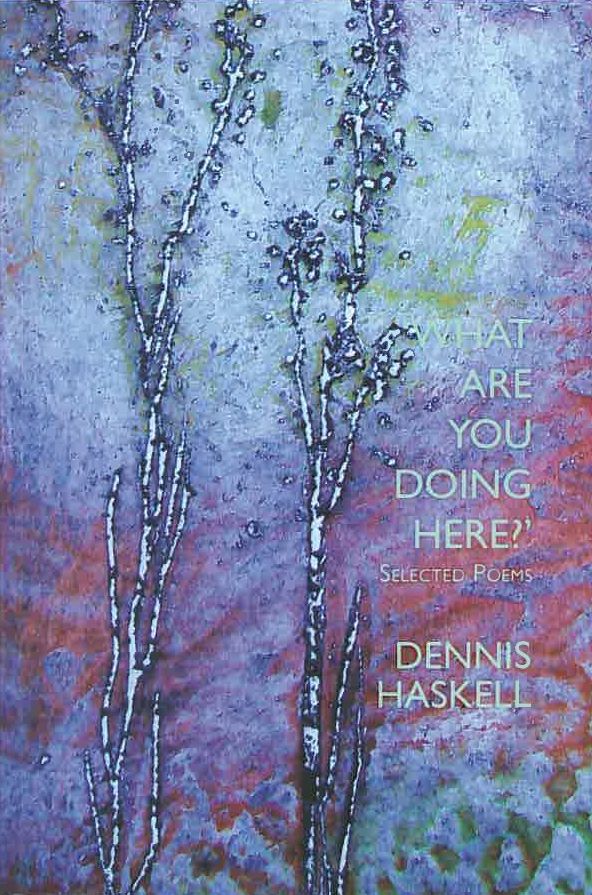

What Are You Doing Here? Selected Poems by Dennis Haskell

University of the Philippines Press, 2015

Dennis Haskell’s new selected is part of an interesting trend. In the past few months three other Australian poets (Adrian Caesar, Jan Owen and Robyn Rowland) have also had books published overseas that, in more congenial times, might well have been published here. In each case there’s a plausible explanation but it’s an interesting phenomenon even so.

In his preface to What Are You Doing Here?, Haskell declares, quite reasonably, that he has ‘been fortunate to work as a Professor of English – fortunate because this meant I was paid to read and think, and to share that thinking with others, including young people.’ Happily, like quite a few other poet/professors (Andrew Taylor and Kevin Hart, to name two), Haskell’s own poetry shows few if any traces of explicit ‘theory’. Indeed, he says ‘I detest academic poetry and seek a poetry that uses the language as fully as possible yet speaks to that elusive creature, the common reader.’

That real but mythical ‘common reader’ is accommodated handsomely by Haskell’s subject matter for a start: suburban felicities (including love and grief), travel poems and tentative metaphysical speculations (or refusals of such). Haskell’s manner is low-key, almost self-deprecatory at times, but language (if not stanzaic form) is important to him. The conclusion to Haskell’s ‘Ars Poetica’ insists on the importance of language (especially the ‘patterned’ language of poetry) to our whole existence. It also reveals, but not to his embarrassment, a little of Haskell’s professorial self: ‘Like a burglar interrupted, writing is incomplete / and in its broken glass meaning arrives, / in just that whereof we cannot speak: / the hologram torch of language, shining in our lives.’ Characteristically, the witty reference to Wittgenstein combines nicely with the resonant assonance of ‘shining in our lives’.

A few of the poems here, selected from forty years’ work, address subjects such as ‘love’ and ‘grief’ directly in language more than adequate to the task (though often undramatic). More frequent, though, are poems which embody the poet’s thoughts about religion, history, the ‘meaning of life’ (or lack thereof), cultural juxtapositions and political justice (both in Australia and overseas). It’s not professorial thinking – it’s thought that grows from puzzling over specifics rather than making experience fit omni-explanatory theories, as is often the way with some (but not all) humanities lecturers.

A good example of this emphasis can be found in Haskell’s poem, ‘What Use Are the Humanities?’. In its second stanza the poet imagines how physicists would walk along a relaxed Sunday shoreline ‘murmuring about gravity waves, / those long elongations of air / that might exist / only in imagination, but / that might measure out / a time before time began.’ In the third and final stanza, for ‘us’ (humanities specialists, presumably) ‘on the packed granules of uncertainty / Sunday’s meaning shines, inconstant, / unreasonable, on the waving beach of ourselves / almost numb with light.’ It’s more than a little ironic that there is a metaphysical dimension here to the experience of both groups, even if their motivating principles are somewhat different.

Allied to this is Haskell’s belief in the importance of the quotidian. The opening lines of ‘No-one Ever Found You’ are a touching example: ‘No-one ever found you self-seeking or dishonest. / Giving is your gift. When you stand / on the spotted tiles, peeler in hand, / large-eyed, intent / on pontiacs, carrots and all the care / for yet another meal, you think yourself / ordinary, like the magpies / that march about outside the windows … ‘The ‘you’ is never named but it is reasonable to assume she’s the poet’s mother, saddened by his departure to the other side of the continent. A similar feeling can be detected in the closing lines of ‘Waking Early’ where Haskell describes early morning Sydney as a ‘honeycomb in the cellophane of early light, / a place where even our dreams / hold us, richly, to the ground.’ ‘Dreams’ being held ‘richly, to the ground’ is a characteristic Haskellian paradox.

But the strongest of all Haskell’s suits is his way with grief. Here, his poems have a disconcerting intensity, even if they’re assembled from simple parts. A poem from his second book, Abracadabra (1993), which has long stuck in this reviewer’s mind is ‘One Clear Call’. Written well before the internet, the poem recounts how an engineer friend rings up looking for a poem to read at his father’s funeral. The poet/narrator suggests Tennyson’s ‘Crossing the Bar’ and begins dictating it from memory over the phone. Successively, the engineer and then his wife are reduced to tears in the process of transcription, ‘registering the scatter of words / as they lift from Tennyson’s dead mouth and your own voice …’ to create ‘that past sensation of syllables sweeping you and your friends / across the bar of technique, of grieving, of consolation.’ It’s a situation where, as Haskell demonstrates throughout the selection, only poetry will suffice.