The Antigone Poems by Marie Slaight and Terrence Tasker

Altaire, 2014

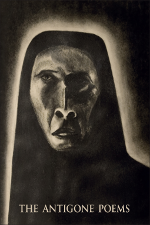

The Antigone Poems is a collaborative work, made up of poetry by Marie Slaight and drawings by Terrence Tasker. Created in the 1970s when the writer and artist were living in Montreal and Toronto, and published in 2014, it is an attractively produced book. The drawings, most depicting faces like tragic masks, divide the five chapters. These images are archaic and chthonic in mood, free from any twee classicising, and match well the equally chthonic mood of the poetry. Most of the poems are brief, suggesting fragments of some larger lost work. Such world as they sketch is made out of primary things: sun, blood, bones.

The book presents itself, in the words of the blurb, as ‘an intensely personal invocation of the ancient Greek tragedy’. The less definite ‘invocation’ rather than ‘retelling’ is a wise choice, though the latter term does appear in the promotional material. These poems are rather a lyric engagement with the story, which really requires its readers to know the narrative ahead of time. This is itself an ancient practice, found for instance in some tragic lyric. The blurb’s reference to ‘the ancient Greek tragedy’ suggests Sophocles’ Antigone, though other plays also featured Oedipus’s daughter (among extant tragedies: Sophocles’s Oedipus at Colonus, Euripides’s Phoenissae). There is a decided theatricality to this book: not only the choice of a character primarily associated with drama and the style of the art-works, but the monologue style of the poems suggest a character performing herself.

So why Antigone? And what sort of Antigone? Most immediately evident is the interiority of the poems’ voice. This is especially striking given the exteriority of the story as it appears in its major tellings: Antigone struggles to assert her obligations to kin over the law of the city, in defiance of her antagonist, the new king of Thebes, Creon. The fixation on death of earlier Antigones does find its way into Slaight’s:

We live our lives The instant between life and death. To touch death always, That is the sun. (p.xxxviii).

She is, though, more oracular and more sexual than Antigones tend to be:

…I only want to purge of godawful pain - so close to losing me - he has to grip - he’s so - what - movement is stronger, hotter, my entire body - where’s the sun - where is he - he’s not afraid, he knows, he penetrates, he’s a fool - to leave me alone - heat’s stronger, I’m pulsing - waves of pain, pleasure - I’m his, what of it - thank god - … (p.xx).

This sounds more like a Cassandra than an Antigone. There is a closer approach to the narrative in the recollection of Antigone’s exile:

In exile I walk on blood I carve a vein I bear sons In exile I carry screams I seek revenge I await my return In exile. (p.lxvi)

Likewise her death, by being buried alive, appears:

… Let the silence reverberate Let the silence break this wall. The word. A moan of blood. Or a spasm. (lxxxii)

These last lines suggest the suicide of Antigone’s fiance, Haemon, over her dead body (a suicide which is already described in heavily sexual terms in Sophocles). The sons are an addition to the traditional tale: for Sophocles’s Antigone, children were high on the list of things that she would never enjoy, as she gave away her life to bury her brother.

Sophocles’s Antigone is famously a play with two centres: Antigone and Creon. To move the action so entirely into the consciousness of Antigone makes the dynamic of these poems quite different from the classic telling. That in itself, of course, is nothing with which to find fault. The relentless interiority, though, means that other characters are only roughly indicated, and there is little sense of what this Antigone is resisting. The result is a generalised voice of defiance, which does have a certain power, but lacks any specific object for its rebellion.

The final poem (lxxxviii) lets drop the mask of Antigone altogether, transforming the voice to that of a contemporary woman reimagining Antigone, who wishes ‘to live all lives, all deaths, encompass all women’. This ambitious breadth, while it does give an all-encompassing quality to the poems, despite their brevity, also tends towards a lack of definition of any specific character. Until, that is, this last poem, where the speaking voice of the poem reflects on how little she feels that she has achieved:

I have written a few words Created a few images Influenced a few lives. I live at the corner of St. Lawrence and Pine. I have three children.

This is an attractively produced and intriguing book. Its strength is really cumulative more than in each poem individually. Its primal, bare bones approach to myth feels a product of its time (Richard Schechner’s Dionysus in 69 was just a few years earlier), but this is not an approach that has exhausted itself yet. Since the book was created, Seamus Heaney and Anne Carson, among others, have contributed to the already crowded list of Antigones. What this one offers is a corner of a broader picture, with both words and pictures in charcoal.