‘Yoked with contrarieties…’

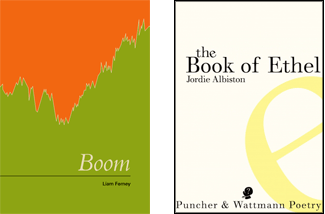

Boom by Liam Ferney

Grand Parade Poets, 2013

the Book of Ethel

Puncher & Wattmann, 2013

Jordie Albiston’s the Book of Ethel and Liam Ferney’s Boom illustrate two dramatic obverses in contemporary Australian poetry. Both are cleverly crafted; both have levels of subtlety and manifest strength; both are linguistically sinuous and inventive, taking liberties with conventional style and syntax; both use local vernaculars in contexts of global cultural pressures; both focus, often minutely, on particular individuals caught at moments of historical change and significance and, therefore, articulate and explore ‘political’ consequences and issues; both play – gloriously, ironically, iconoclastically – with language registers as a way of exposing implied ‘bigger pictures’. And yet these two collections are worlds apart in focus, style, nuance, framing and poetic affect.

This is Albiston’s seventh book of poems. For it, she has developed, appropriately, a tight ‘square’ form of a seven-line stanza (is it a septet, a septina, a septode, an antipodean radicalisation of the tanka?) each line of which has seven syllables. There is a formality both mathematical and musical in the architecture of the poetry. It’s a verse autobiography (rather than a verse novel) of her maternal great grandmother’s migration from Cornwall to Australia and her life as a minister’s wife. Each stanza is a stave in the larger score (following her marvellous, mesmerising cantata Vertigo). Individual squares of verse are like parts of a patchwork quilt – Ethel works as a seamstress, though maybe the textile Odyssey of Julie Montgarrett is a better analogy – made from fragments of historical documents, letters, diaries and published articles and stories: Ethel Overend’s actual works. As well, the Book of Ethel has several echoes of an Old Testament hagiography, albeit this saint’s life is impressionist, ironic (is it possible for an Australian reader to escape the ghostly consciousness of Ern Malley?) and vocalised. At the same time, the stitchery, the voice, the politics are distinctly feminine/ist as the poems reposition a marginalised life and sensibility at the centre of the cultural canvas.

Individual poems echo traditional lullabies and nursery rhymes in language richly infused with Cornish dialect (see glossary at the end: gesyow [joke] and hwerdth [sister] seemed almost onomatopoeic to me; ydhyn [bird] seemed delicate, melodious in the poem and zack [sixpence] was, I thought, an ‘Australian’ word which I learned as a migrant from England, arriving in Australia in 1960). Its postcolonial reimagining of part of Australia’s history positions the reader to look from a wife’s eyes at her husband’s (and society’s) work and busyness. There is, too, in the relative plainness of Albiston’s form and language, something of the unadorned simplicity of the Wesley hymns, so much part of the Methodist tradition to which Ethel, as a minister’s wife, was bound. Nonetheless, despite the overt restraint and modesty in the poetry, there is an emotional richness and complexity in the constantly affectionate and uxorious tones and tropes of the poetry. Ethel is a loving wife, a good woman, an emotionally engaged and insightful diarist.

Ferney’s Boom, his third collection, is, by contrast, a forceful, consciously iconoclastic collection of varied-form poems. ‘Free verse’ seems too bland and inaccurate, as this collection has an accomplished variety of stanzaic forms, including a wonderfully wry sestina, several couplet/triplet poems, some proto-sonnets, plus across-the-page pomo scripts and (rock) music lyrics/raves. If Albiston’s verse could be described as ‘centripetal’, Ferney’s would be its ‘centrifugal’ counter-thrust. This is poetry that refuses to be contained – it keeps spilling over its boundaries. As well, the poems in Boom are overtly transnational, abrasively vernacular. They scope Korean argot, American music, and Australian travellers’ agnostic scepticism. There is not one narrator or autobiographical consciousness – the prevailing points of view are fragmented, unreliable, consciously incomplete and performative. The poems defy simplicity and unity, and are self-consciously postmodern, delighting in their omnivorous and rupturing juxtapositions.

This is poetry that crowds you with high-res, conflicting takes. Ferney’s poems are punchy, relentless and unsettling. They are concerned and enmeshed with global cultural politics and international urban experiences: movies, drugs, cities, rock music – typically cynical. From the opening poem ‘Think Act’, which pushes ‘cyberpunk memories’, the words and images assault the reader, demanding a consciousness that can think in several frames at once: from, ‘at home on the telly Korean newlyweds / roadtripping through alice…’ to, ‘Frontier Lands: V. Good Day for a Hanging’:

…put away the classics try your hand at fan fiction … techniques are more or less the same cane chair ballet poetry a moment in madness this is nightmare billboard…

I don’t agree that ‘techniques are more or less the same’. His poems seem to illustrate this clearly. But the poetry pushes on, quashing my objection with its clever almost-aphorisms.

The fine opening poems suggest a context of cultural alienation, dispossession and uncertainty.

We prick at the voodoo doll of our routine

& there is an absence of transcendentals, of candles…

This life is on fire and some kid has buggered the extinguisher…

(‘Saturday’s Typhoon’)

there is no substitute

for thinking but abc asia and soju come close…

that piss building in your bladder

(‘sign on the dotted line’)