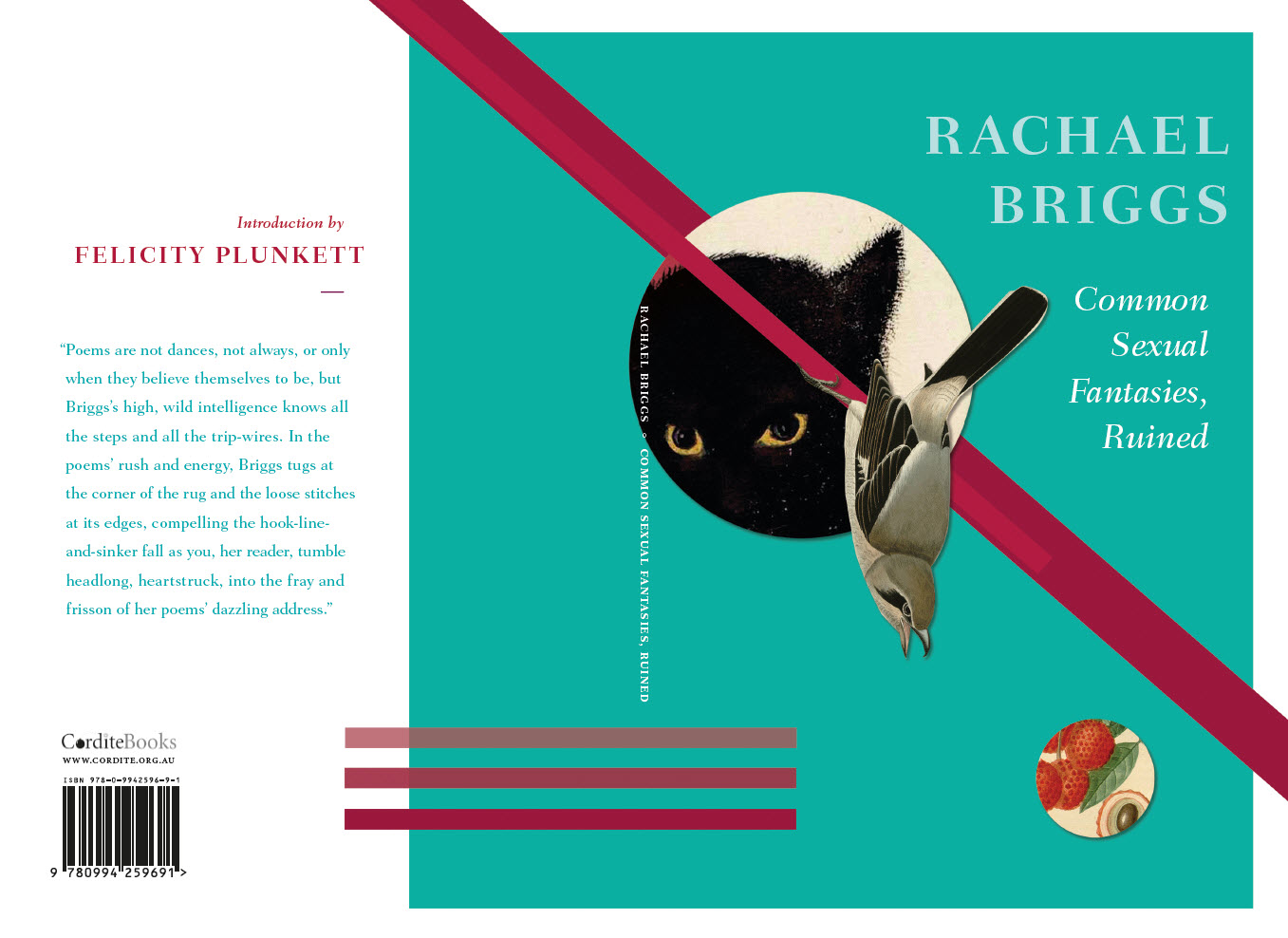

Cover design by Zoë Sadokierski

The polka originated in nineteenth-century Bohemia. A dance for two, it is reputedly simple to learn. Three steps and a hop, in fast duple time, with various steps – Turning Basic, Pursuit and Waltz Galop – an array of positions, sequences and rules. Do this, but not that. Proscriptions and prescriptions, as David Buchbinder puts it, talking not about the polka but the push-pull teaching of gender regulations.

Word pairs can work this way too: push and pull, good and bad cop shoving the subject in different directions, three steps and a hop, a one-two punch from one angle, now another. Common sexual fantasies, ruined. A cliché – ‘pull the rug from under you’ – shorn of its verb, twisting your attention to the eroticism of its nouns: ‘the rug from under you’.

Writing about Rachael Briggs, Justin Clemens recently noted how rarely you find yourself in the presence of ‘such incandescent genius’. He calls her debut collection, Free Logic, ‘a truly strange and brilliant book’. I was surprised to read this. Osip Mandelstam wrote of a poem’s having a ‘secret addressee’, and when I read the incandescent, strange and brilliant manuscript that became Free Logic I had no doubt its secret addressee was me. Briggs writes directly to you, invoking, challenging and interrogating with disarming and seductive focus. Her poetry holds your gaze.

Do you, she asks, in the prefatory mesmerism of a ‘guided meditation, proceeding backwards’ (of course) through the book’s four parts, have secrets up there? Up there in ‘the inside of your own head … more tractable than any pumpkin or melon’. The meditation swirls around logic and equations, language, closets and metaphor with the whip-smart hospitable wit and whimsy of this poet-philosopher who speaks only to you. It suggests the scope of the poems’ – but not, perhaps the extent of Briggs’s own – exuberant imaginative and formal playfulness.

Philosophical problems abound. In ‘Belief and Knowledge’ the protagonists are imagined as twin-like: ‘can hardly tell / themselves apart’. In ‘The Access Problem’ the alternative lines of a querulous interlocutor hack away at the poem’s fairytale narrative, dramatising a bifurcation between concrete and abstract realms. ‘Ambition’ posits that ambition itself is a ghazal, its refrains, like its ‘puffy-proud …chest’, stuffed with feathers.

The ghazal’s signature is ‘Rae’. The chimeric Rae moves through the poems’ hall of mirrors, catching the irreverent poet razoring the seams (of form, propriety, pretence), catching her eye in the mirror, catching her out and in, catching your breath and hers. Shrike and butcherbird chorus: ‘it serves you right, you pervert, Rae— / you dream the blade; you cut your waking throat’, a friend comments: ‘Jesus, / friends have boundaries, Rae’. There is a letter from ‘your faithful daughter, Rae’. Lipstick kisses are blown to Ray, but a receipt is ‘made out to Rae’.

Love may be, conventionally, ‘tab A in slot B’ (my rhyme, not Briggs’s), but in this ‘secret spacetimey, / disguised-as-a-phone-booth / armoire’, the labels itch, and it’s better to ‘snip off all the tags’. Poems are not dances, not always, or only when they believe themselves to be, but Briggs’s high, wild intelligence knows all the steps and all the trip-wires. In the poems’ rush and energy, Briggs tugs at the corner of the rug and the loose stitches at its edges, compelling the hook-line-and-sinker fall as you, her reader, tumble headlong, heartstruck, into the fray and frisson of her poems’ dazzling address.