A man might spend his life in trains and restaurants

and know nothing of humanity at the end.

Aldous Huxley, Along the Road: Notes and Essays of a TouristThe world is medium-sized.

Michel Houellebecq, Lanzarote

Romania (Part 1)

We've been on Romanian trains before and so know to expect the palinka-quaffing mid-morning travellers pluming smoke in every carriage. Our train – a compartment-style rattler with torn and sunken, broken-springed seats – is long and packed, dragged by an ancient resilient-blue Soviet engine. Not long into our journey and golden-toothed Romany begin to stroll the corridors, be-hatted and wizened with their accordions and violins and shining smiles.

Scythers on their way to uncut fields sit open-vested, full of drink and the train's lurch. The jagged mountains disappear sometimes; we burrow into the pitch of tunnels and emerge onto valley floors where combed farms with wildflowers bloom and wooden villages, each with a shingled church spire prodding its orthodoxy at the sky, are cut and crafted from the surrounding evergreens. Folk in the fields here build their haystacks pencil-thin; horses pull the work of days atop carts through muddy town squares.

An elderly woman with her hair wrapped in a scarf sells beer and chocolate and apple palinka, walking the train's length with a steel esky on her arm. This train, skirting the edge of the Ukraine, is taking forever to reach our destination. Not for a second do we mind.

Train of Thought

How do we remain so unlost travelling through the everyday? What places will trains travel in ten – a hundred? A thousand? – years from now?

Manhattan

The coldest weather in a hundred years ices Manhattan. The Statue of Liberty – closed for renovations – seems a tiny off-white stalagmite on the grey and eddying harbour. Cold weather warnings are everywhere. This temperature is dangerous. The duckponds in Central Park steam and Ground Zero is a cold big hole with gathered street pedlars. So Ho is brittle, bourgeois, empty. There are no public toilets in Times Square so I piss in an alley and then go to watch ceramic animals being auctioned at Christies. Where do homeless folk go in weather like this? At McDonalds the seats slope uncomfortably forwards.

At least the trains are heated. We rattle underground below Manhattan and ascend to cross the icy Hudson. Our train is old and scuffed and shunts on its elevated tracks through the broken-glassed industrial burroughs; we peer into the barred windows of 3rd storey apartments. The beachfront at the end of the line, Coney Island (or Little Odessa, as some locals prefer) is frozen silver. Michelle and I agree: we need bearskin hats like every second émigré, as well as big servings of their hot borsch and sauerkraut, fried meat with pickled everything.

Women in jumpsuits, mink, and piled beehives rush in the streets. Neon signage flashes in Cyrillic while American cops twiddle their sirens in mounting, slowed traffic. In the dead of winter the theme parks are shut. We get on another train and exhale cloud, rubbing our hands at the thought of Chinatown's dumplings. The burroughs, late afternoon, are a shaded and darkening dystopia. In the distance, Manhattan has begun to fill with light.

Auschwitz-Birkenau

The sharp retort of the unspeakable. Tourists are gathered inside the chamber at Auschwitz where tens of thousands of people were gassed and incinerated by the Nazis, and take photographs. Birkenau lies three kilometres away. There, where the rail tracks end inside the boundaries of the death camp, I am left wondering how many of the disembarked looked back, to see the gates and guard towers that I can see and

when they looked forward, what

Train of Thought #2

In David Nye's American Technological Sublime, John Stilgoe notes that trains 'and particularly the fast express, struck few observers as a monstrous machine soiling a virginal garden. Instead it seemed a powerful romantic creature inhabiting an environment created especially for it.'

India

One

One

The noise of advertising crescendos through the station's intercom above blaring radios attached to dozens of samosa carts wheeled over toes and past mobile newspaper stands whose owners are yelling in Hindi while beggars peddle strange miscellanies from wobbling trolleys. Trains everywhere hiss squeal roar clang whistle idle fire – almost anything but wait silently. A mass of Delhians seethes from one platform to the next in a trample of shouting commuterdom. Holy cows loe on some platforms. Touts sharpen the din. Outside, a cacophony of rickshaws and taxis and busses wait; the buzz of these and their shrill drivers offset by some deeper mechanical grind, a sonic chaos that belies the psychic dissonance of this encrazening megalopolis. In the station's tourist lounge (strictly foreign passports only!) travellers glance wide-eyed, and sweat.

Two

120 kilometres in just over four hours; train delayed by five; I am hallucinating chatty myna birds discussing metaphysics after a bad prawn in forgettable Goa (where hash and pills and powder are de rigeur). This journey, my tripping is involuntary: the entire time I heave bodily over the smeared pit toilet at carriage end and wish to India's uncounted gods for this rolling sub-30kph hell to go quickly.

Three

Our train stops at a station somewhere between Varanasi and the Bodhi Tree. Near-naked children mill on the platform, push their hands through the steel-grilled windows as the train slows, rubbing their distended bellies. Travellers in India echo among themselves 'don't give money' because 'it encourages begging': we hear how, in parts of India, Dalit ('untouchable') children are still maimed to increase their begging prospects. We hand food and coin through the windows and wonder what we're perpetuating. These children (hungry, here, now) have been born in a place where organised charities don't exist. More children arrive. We also hear myths whispered in Delhi of begging children controlled by Fagin-esque overlords who take everything from their enslaved minions. People choose what they believe. Our train begins to shunt forward toward the next station, where the same thing will probably happen. It is impossible to do enough. It is impossible to think about any of this clearly.

Four

'Teacoffee? Chai chai chai chai? Teacoffee?' India rolls past. Verdant paddies and water buffalo and thatched huts and rocky mountain temples and red-arsed temple monkeys and terrifyingly ramshackle cityscapes and rivers moving slow and full of the dead and, no matter where and when I look out, endlessly, people.

Five

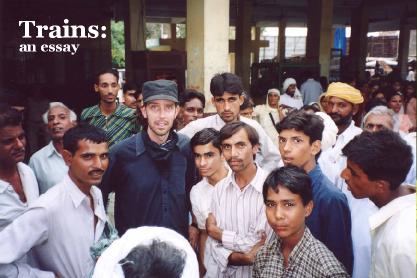

Every time the trains stop and we alight, we are surrounded by young Indians intrigued to know 'what is your good name?' and 'from which country you are?' Those with cameras cram friends into shot around us; Michelle is frequently handed a newborn. The married women hide grins behind raised saris while the men wiggle their heads and beam. I'm always asked 'love marriage?' and, when I nod, the response is somewhere between bashfulness, awe, lusty disbelief, and bewilderment (though, as we come to understand, this is An Almost Universal Response To Almost Anything At All We Say during our time in India).

Etymologies

'Train' derives from the Latin tragere 'to pull' or 'draw' and, though there were streetlights in the columned promenades of ancient Rome, there never were any trains.

'Locomotive' is from the Latin in loco moveri: 'to move by change of position in space' – but it seems more the world's spatiality (medium-sized now) that's altered. Trains? Are as if early model proto-leviathans venturing into the unknown –

Train of Thought #3

Jean Baudrillard, in his epilogue to Luc Delahoye's L'Autre (a book comprised of covertly-photographed commuters on the Paris metro), states 'there is no bringing of these people into psychological focus'. On trains all over the world we feel enclosed, uncomfortably close to the local humanity; even in the un-densely populated Melbourne, peak-hour trains can seem impossible without sunglasses and novel. What is it about the proximity of strangers? Why do these vast groupings (unassimilable and otherly, though only a salutation away) create such disequilibrium? How many times do our eyes lock – accidentally, fleetingly – with those of fellow commuters? What is it about this gap of centimetres that stifles any possibility of interaction to its zeropoint?

The Reign in Spain

At 1pm the streets of the town we've just arrived in are deserted; Vigo is mid-siesta. We grind our molars and argue over anything – nothing – after a second sleepless night on a bus speeding out of Portugal and toward Bilbao's Guggenheim. Our packs and the company of the two Canadians accompanying us are heavier than usual. We stumble over cobblestones and watch folk in bars watching television. There's something in the air today – or maybe I'm just projecting my exhaustion into the alleyways; they're full of strangeness.

We arrive at a bar and agree to churros and coffee. On the TV a twisted black carriage spills a bloody nightmare out its side. Another shot shows another ruined train. The commentator speaks rapido and in raised tones. It takes seconds to assimilate, process: what are we being shown? We find someone who tells us 'maybe 500 dead in Madrid's trains' before asking if we're Americans. My mind fills with Al Qaida and ETA as if 'who? who's done it?' is a way of gathering comprehension. Jose Maria Anzar, Spain's conservative-party prime minister, denounces the terrorism a week out from a national election and states assuredly it is the work of Basque separatists.

That night we travel sleepless aboard another bus toward the unofficial Basque capital. The cadences of weirdness are even stronger in Bilbao; at the Guggenheim, the permanently exhibited 'Snake' – two pieces of long warped steel which viewers are encouraged to walk between – is haplessly resonant. In the evening Michelle and I are trapped and pushed along by the terrible flow of one million protesters in Bilbao's rainy streets. Almost every protester has an umbrella; the march is slow, silent, surreal. It emerges later that the terrorists are North African extremists, and that the government knew this all along. Anzar, days later, is thrown out of government.

We pause for a minute, and think about the Tampa, the Australian detention centres, the lies of a government that refuses to apologise and, right then, wish we could all vote as decisively as the Spanish.

An Echo Reverberating Inside the Privatized Trains of Melbourne

'Just take yer feet off the seat there and show us yer tiggit please.'

'I don't have a ticket. Sorry.'

'Roight and is there anyreasonadall whyya nodcarryinavalidtiggit today?'

'Umm-'

Romania (part two)

We are warned by zealous transit officials not to place our backpacks on the seats of Bucharest's new Canadian trains as they burrow away from the city centre where once there was a venerable old town full of music and beerhalls but now there is Ceausescu's unfinished thousand-roomed People's Palace, looming atop an artificial hill. The former tyrant, while demolishing his city's heart in a scheme to build an empire, created a diaspora of inner-city inhabitants, whom he housed in socialist-style apartment blocks. The inhabitants' dogs didn't fit inside their new apartments and so were left behind: their feral descendants rove the streets of central Bucharest in packs. These are strictly forbidden inside the new metro but sit and scratch at the entrances where it's warm and the company plentiful. There is something wounded about this city with its vast polluted boulevards and obvious poverty, its empty shopfronts and glaring thugs cruising in shining imported cars. But at least the new trains are there – deep below and pulsing, pristine in the metro's arteries.

Modernist v Postmodernist

'You are not the same people who left the station/ Or who will arrive at any terminus,/ While the narrowing rails slide together behind you.'

TS Eliot Four Quartets.

'-those raiders and predators who plunder customs and cultures, faces and landscapes that are really none of their concern. Having nothing to do with them, they don't even really see them.'

Jean Baudrillard L'Autre.

The Vast Hungarian Flatlands

It's easy to become forgetful in the old-style compartment carriage rocketing west over the Great Plains of Hungary: unremarkable, flat, with a big lake in the middle. The railway sleepers thrum in iambic pentameter, hypnotic; before long I'm deep inside a private conversation with a dream. 4.30am, and I feel someone's hand in my trouser pocket and rouse myself to see a droopy-moustached chap with dead eyes smiling crack-toothed with his hand on my wallet saying in bad English with matching breath 'Oh. We. Need. Light. You. Smoke?' and while my mind is Houdini-ing out its disturbed sleep I smile back and mumble 'No, sorry, I do not' to him and the man behind him who's got his chin almost on his friend's shoulder.

They leave I go back to sleep I wake up and fumble the compartment door then lurch out to the corridor into which these my newest acquaintances have quickly vanished. Feels like I've been anaesthetized but my wallet is still with me and Michelle is sprawled, on the seat and unmolested, so: back in our compartment and settled, I reach up and (nodding 'yes yes' to my recently awoken inner-world-champion at the game of 'what if') snib the handle on the compartment door.

A Non-Exhaustive History of Roller Coasters

One

Prototype roller coasters were invented in the frosty climes of St Petersburg in the seventeenth century when gentry and peasants alike sat upon specially cut blocks of ice placed on specially constructed slopes of ice-whereupon gravity took control. This fashion spread to France where the weather was not cold enough and so a waxed wooden slope plus sleighs with rollers was contrived. In 1850 the French took things to the next level with the Centrifuge Railway – able to perform loops-the-loop. This was a contraption authorities banned almost immediately.

Two

In the mid-nineteenth century miners deep in the Pennsylvanian mountains had the need to transport coal down from their mountaintop mine to portside. And so a 40 mile long railway was constructed. The miners, filling the rail cars, shoved. When the cars arrived at port they were offloaded before mules dragged them back. Due to a gathering surplus of mules atop the mountain a carriage was soon invented to transport them down again, unmanned, trailing the coal cars, and at a speed occasionally exceeding 100 miles per hour. Before too long folk from everywhere were queuing behind the mules.

Three

At the turn of the nineteenth century, companies built amusement parks at the end of train lines to attract weekend visitors who would alight, pay cash, and then ride on stranger versions of the trains they'd just got off: scenic railways, gut-heaving coasters on wooden hills, dioramic rides with automata and brakemen. In Melbourne, St Kilda's Luna Park was opened in 1912, engineered by the same folk who built Coney Island's park decades earlier. Survey maps from the 1860s show the St. Kilda area covered by a small lagoon – 40 years later, this was supplanted by a Big Dipper lit up at night by 80 000 lightbulbs.

Emu Plains to Katoomba

The hot and prefab-dusted Australian badlands scan past like eucalypt suburbs in the shadow of utopia. The Blue Mountains rise in crags in the oncoming distance. There is something chthonic, dark, mystical about the looming landscape – something we descendants of terra nullius colonists aboard our snaking trains will maybe never understand.

Romania (part three)

The slow Romanian State Railway (CFR) stops regularly at obscure, unpeopled Transylvanian stations. In the socialist era, factory workers used trains to get to work – long abandoned now, the trains still stop at these inert steel factories and quarries, dormant on their scarred hills. It's eerie to sit beside these broken machines, waiting, while nothing happens, except the breeze, which lifts and then replaces, lifts and then lets fall again the loose flaps of corrugated iron in an unnatural kind of a Sisyphean motion.

The Empty Spirit in Vacant Space

What sort of distances have we travelled aboard trains? Ralph Waldo Emerson wrote 'fear haunts the building railroad, but it will be American power and beauty, when it is done.' Wallace Stevens wrote in 'The American Sublime' how 'One grows used to the weather,/ The landscape and that;/ And the sublime comes down/ To the spirit itself,/ The spirit and space,/ The empty spirit in vacant space.' I wonder: do trains indicate how far we have come in our mechanised, human universe? Are trains full of empty spirits, moving through hyper-real space? Are they a measure of the ontological distances we've come thus far?

Bibliography

Robert K. Barnhart (ed.) 1988 The Barnhart Dictionary of Etymology (New York: The H.W. Wilson Company).

Jean Baudrillard's epilogue (trans. Chris Turner) in Luc Delahoye1999 L'Autre (London: Phaidon Press).

T.S. Eliot 1969 The Complete Poems and Plays (London: Faber and Faber).

Ralph Waldo Emerson 1960 Selections from Ralph Waldo Emerson, ed. Stephen E. Whicher (Boston: Houghton Miffin Co).

James Marston Finch 'In Defense of the City' in Proceedings of the Academy of Political Science, Vol.27, No.1 (May 1960), pp2-11.

David E. Nye 1994 American Technological Sublime (Cambridge, Mass: The MIT Press).

C.T. Onions (ed.) 1992 The Shorter Oxford English Dictionary (Oxford: Clarendon Press).

Wallace Stevens 1955 The Collected Poems of Wallace Stevens (New York: Alfred A. Knopf).

www.brittanica.com/coasters/, www.lunapark.com.au/pdf/LP%20History.pdf

www.ultimaterollercoaster.com