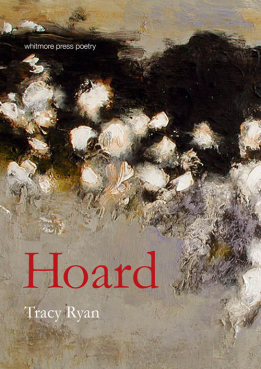

Hoard by Tracy Ryan

Whitmore Press, 2015

Breaking the Days by Jill Jones

Whitmore Press, 2015

These two slender and handsomely designed volumes of poetry are the result of the closely con-tested 2014 Whitmore Press Manuscript Prize, of which Tracy Ryan and Jill Jones were joint winners.

Due to this accident of ‘joint’-ness, there would be a temptation to recognise a connection be-tween these chapbooks, even if they were wildly disparate in their concerns. But one does not need to overreach to see a correspondence between them. Both are inhabited by speakers explor-ing something that should feel tangible, safe, concrete – ancestry and homeland, in Ryan; the everyday world, in Jones – which has, perhaps unexpectedly, become secretive, inaccessible, en-igmatic, acting according a private agenda, and in ways that the voice observing them does not completely understand.

The briefest glance at the contents page of Tracy Ryan’s Hoard reveals its obses-sions; eight poems in the chapbook contain the word ‘Hoard’ in the title, while a further nine contain the word ‘Bog’. This is the terrain, both geographic and imaginative, that the collection circles: the bogs of Ireland, and the hoards of jewellery, coins, or other valuables which were of-ten buried within them. These bogs have long been (and remain) places of concealment and preservation:

For years it was tended and kept mute trampled and stamped down a bumpy carpet harnessed to household use a warmth of sorts still shock-absorbent swallowing all conceivable laying down more mass and thickening like skin where wounds might otherwise have been (‘Bog disturbance’)

This is a sombre, mysterious environment. The bog is ‘spreading & dense & various’, it is ‘steadily unstable’; cold, but ‘locking up heat’. Most of all, though, it is absorbent, capable of ‘taking and taking’ rain, or anything else, for that matter, into itself, ‘swallowing’ what it can and what it must: from excessive water, to hoards, and human bodies, which are preserved intact.

While they are permeable, and accommodating, the bogs nevertheless display a determined re-sistance .The speaker, making forays into them, is continually ‘feeling the mass yield and spring back’. This insistent sense of the bogs and the hoards within them as somehow owned and un-owned, knowable and unknowable, is connected throughout these poems with the speaker’s rela-tionship with Ireland, the home of many of her ancestors. This speaker, having arrived in Ireland, feels both connected to her ancestral home, and alienated from it; she is the ‘ghosted / great-great et cetera’ who has been ‘all my life looking high & low for you’, having been displaced to a ‘red gravel’ landscape so unlike the place from which her ancestors have come. The markers of con-nection such as common facial features become meaningless:

Mistake to think because a face here is commonly featured there’s anything in it That was a stamp carried wide & much repeated (‘The changeling addresses Ireland’)

The speaker of these poems is continually excluded from belonging – ‘I am turned out / too easy to cite eviction & famine’, Ryan writes; and at other moments, ‘I’m only the dummy,’; ‘I betray with palate & tongue-tip / the wrench in history’; ‘I cannot come home’.

At times, this sense of a continuity which cannot be reliably traced is echoed through the pat-terned sounds in Ryan’s language. For instance, in this passage from ‘Hoard hider’:

velvet selves bereft attendant on resurrection I know this location chosen before I was even born

The repetition of sounds moves subtly; slant-rhymes and assonances recur and then fade, to be replaced by others. The feeling of continuity is thus maintained; yet, later words do not chime with those at the beginning of the sequence. This effect mirrors the speaker’s dilemma; she finds herself at the end of a chain whose earlier links now seem to exclude her.

Amongst all this anxiety, there are moments when the speaker imagines the bog as a (feminised) entity, capable of suffering, and tolerant ‘to a fault’ of people’s insistent trespasses against her:

Did you never understand she existed in her own terms with her bog priorities her bog predilections her bog sensibilities. (‘Directive’)

The speaker reminds us that the bog is under threat from turf-cutting, and that it has become the receptacle of garbage in modern times, rather than of bodies or valuables. Now ‘cast-offs old cars white goods no longer wanted’ litter the bogs, and a callous ‘we’ imagines that the bog is unaf-fected – ‘as if by mere compliance she does not register’.

This extends past empathy with the bog; the speaker seems to imagine the bog’s experience as analogous, in some respects, to her own. The ‘bog body’ is capable of a kind of birth, in its giving up of bodies, or hoards, while the speaker informs us ‘Two children were pulled from me’. This phrasing renders the mother bog-like, in that she becomes an object from which things are removed, with a degree of force, perhaps even violence. But even this identification is contested:

If I write the bog as the Poor Old Woman or even the Rich Old Woman treated poorly am I not complicit in a history of dangerous conflations is the earth our mother is it beyond gender (‘Rhetorical’)

The title of the poem, and its lack of question marks, seem to flatten enquiry; this speaker knows these questions must remain unanswered. To journey into the bog and confront what it will and will not reveal is to accept that there may be no answers at all; only a contemplative awe at the bog’s ability to survive and to preserve. Poetry, for this speaker, seems to share several of the bog’s qualities, in that it allows her to reveal and to conceal, and to preserve her own ‘dented treasure’.