New Works on Paper by Luke Beesley

Giramondo Publishing, 2013

I’ve been meaning to write this review for a year – in fact, there’s a wine stain on my copy and I can pinpoint the exact date that I first put it on my to-do list (i.e. engaged in other work → frustration → tipped glass). Despite all of my sideways swerving, a year is a good amount of time to let Beesley’s recurring bees swirl around the head; a year helps one to figure out their tune. Or, as the poet writes, ‘It’s not about bees. There are no bees.’ Have I tipped the wine glass again?

New Works on Paper reminds me of Stein’s Tender Buttons: windows open out to an ‘other’ view, wholly within our grasp but difficult to articulate; a sensual vision can feed the poet as well as food (‘You wear your aubergine swimmers that answer to no one. I peel you’ (24); ‘You caught the asparagus-green, oiled and wok-fired lights’ (25)); philosophical sketches on modern living are passed through a (green) prism: ‘After taking pencil shavings (green) out of the sharper than the air’ (15); ‘The green light inside/ a canary’ (54). Indeed, the following poem suggests the poet’s nearness to Stein, as he quotes her in the epigraph (‘all is as all as, is yet or as yet’):

Funny, to be in nature might be like

what? It is surprisingly icy, the sky.

Is it something within, or without?

I see as much from a window, hear.

I collect twigs. Fantastic. It’s a word

I’ve been meaning to use it

won’t take

isn’t necessary, or this evening – sky.

Near is nature might be like. As in it is.

(‘In Nature,’ 7)

I first understood Picasso’s paintings when someone told me that the artist was intent on capturing multiple moments in time; a moving image collapsed into one frame; several points of view at once. One might think of Beesley’s poems as a Stein-Picasso hybrid for the 21st century: ‘Assembled incidents – no sadness. Nothing as obvious. The noun collection. A collection of poems (grief) the clipped organisation in the word and, working to define it, I sit down. […]’ (A 1 Bakery, 22).

New Works on Paper is split into three sections: ‘The Word (Otways)’, ‘Pencilled Losses (Northcote, Jan-May)’ and ‘Frames.’ The first two refer to locations in the State of Victoria, Australia – the Otways is a national part in the South West of Victoria, popular for its camping grounds, walking trails and birdlife; Northcote is a suburb of Melbourne. One could assume that poems in these sections were written in these locations, and that place is important to the poet as a sort of framework for thought. As a reader, I find it refreshing that these places are not immediately recognisable within the poems, but (possibly) hinted through brief actions or engagements (chopping firewood, preparing tea, watching films).

We ‘work to define’ the edges of this uncanny universe – and a reader less familiar with abstract poetic approaches might become frustrated with the less-than-concrete perspective/s being offered – though it is better to relax into the happy assemblage of spaces, film and art references, literary influences and flighty things, and to revel in the wake that is left by these things that we encounter in everyday life. And when the attention isn’t distracted by bees (they’ve fallen into a tea pot), birds command the air, or else fill other spaces, from ‘knuckles leaving his chest like a budgerigar lost to the trees’ (30) to ‘a following wren’ (4); ‘sparrows stuck on a fence-line in the corner of a sketch’ (21) to ‘[h]ands mov[ing] like wrens probably robins sewing up a point or tone, ruffled’ (59). ‘Birds are endless engagements. Nothing idle about them’ (6). Of course! These works on paper are airborne, on the move. As in, one does not receive a realist impression of a landscape, person or thing after reading Beesley’s poems, but a swirl of interconnected things, restless as music: ‘What he saw were waves. An impress he thought the flute had left’ (20).

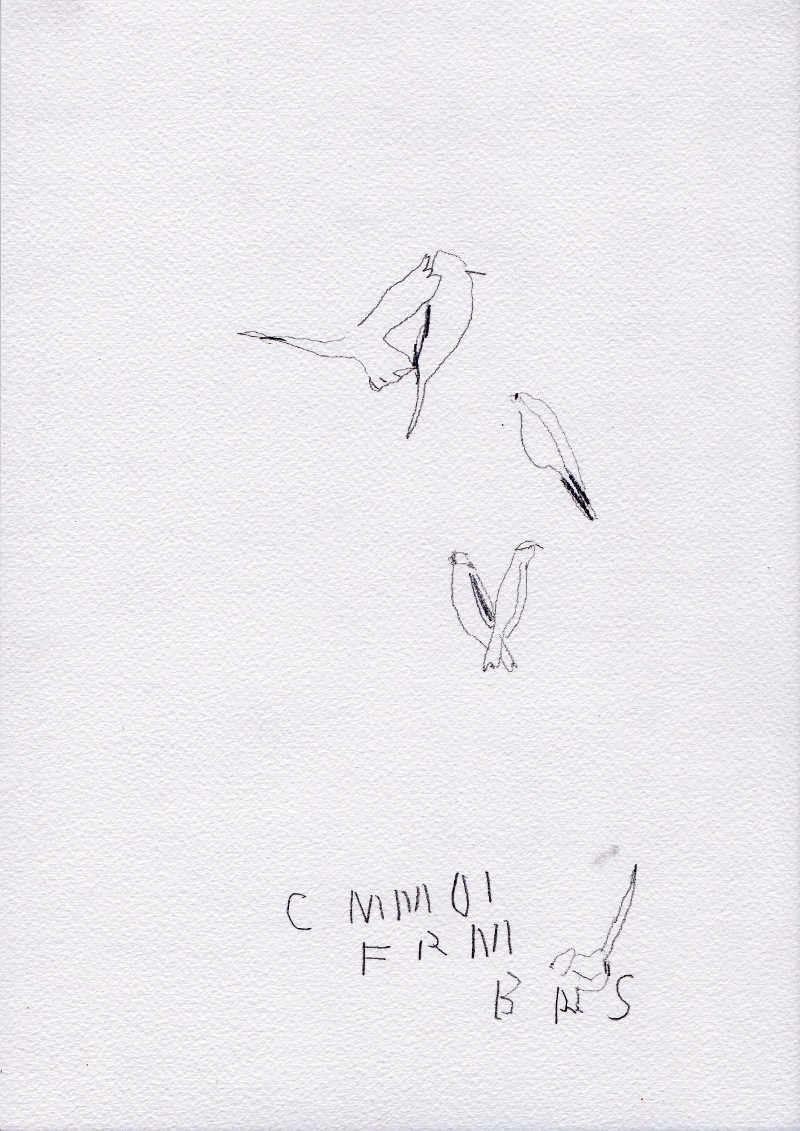

Beesley is also a singer-songwriter (his debut EP Bees Nudge the Mouth of a Feathered Rose carries the same title as a poem in New Works on Paper) and a visual artist. Indeed, in 2013 I commissioned him to supply a series of art works for Rabbit as a poet-artist, and one of the images was ‘Common Farm Birds’, pictured below. A kind of mastery of clumsy charm; deceptively simple; revelling in the known-unknown: Beesley’s artworks seem more vivid for what is not there, skirting an outline for a new perspective of our surrounds, as if divorced from political context and sentimental messiness.

Common Farm Birds #15, 2010, pencil on paper, 297 x 210mm.

Common Farm Birds #15, 2010, pencil on paper, 297 x 210mm.

His poetic works on paper offer similar characteristics, ‘varied folds of scribbled feather-work,’ as he writes in the poem ‘On Birds’ (6). These are poems that give us minute details: light catching the hair of a woman’s stomach, a discarded fingernail, ways to write and draw ephemera without stilling motion. Quoting John Ashbery: ‘Leaves around the door are penciled losses,’ the poet suggests affinities with this view, preferring to discard the muddy footprint in favour of a more poetic trace, signifying movement.

To ‘figure out’ Beesley’s poems, then, is to let them flap about your periphery, not touching down. And to let them do this for at least a year.