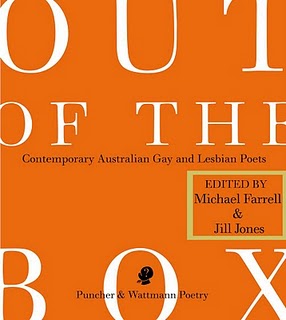

Out of the Box: Contemporary Australian Gay and Lesbian Poets

Michael Farrell and Jill Jones, eds.

Puncher and Wattmann, 2009

Out of the Box: Contemporary Australian Gay and Lesbian Poets is an elegantly-published product. The shape of the book looks like a miniature hatbox, the title of the collection leading a reader to anticipate exciting and colourful content. This ground-breaking anthology is a reasonable gathering of poets, currently writing under the descriptors of gay and lesbian in Australia.

As I am aware of a number of poets not included in the anthology, I have been wondering about the selection process in compiling the publication. I became aware of it accidently, stumbling across the Queer Issue of Stylus Poetry Journal and reading about it in Jill Jones’s Introduction to that issue. As far as I know, there were no calls for submissions through poetry contexts or the l/g/b/t/i/q press. There was no invitation for submissions, for example, on the community-publishing gay- and lesbian-ebooks website. It’s as if the editors only put the word around their networks of poetry mates. If this is what occurred, I am partially critical of this process. At the same time, the selected poets elicited great surprises for me as I had no idea that many of the poets included qualified for inclusion under the names gay and lesbian.

The editors’ deliberate intention of making the anthology provocative, to go beyond the boxes of national, sexual and subjective constraints, makes it a page-turning, pleasurable read. The range of subject matter encompasses versions of the self, history and politics, social identity and language as well as love and desire and a range of gender styles. The anthology is organised in alphabetical order by the first word in the title of each poem. This organisational strategy generates a more democratic way of publishing the poems, highlighting the pieces more than their authors.

As history is a significant trope in the collection, Pam Brown’s ’20th century’ is a pithy evocation of the changing political attitudes in the late-twentieth century:

It's all just clothes, makeup and hair. And as we were the tootlers we tootled along to the popular anytime anyplace ...

The hmmm of reflection, of critical appraisal in the decade from the mid-sixties to the mid-seventies, was replaced by the wow factor as the glamour and spectacle of the last decade or two of this millennium merged into “untrammelled enthusiasm”.

‘About the Self’ by Martin Harrison is a long, first-person reflection, describing the sequence of events characterising a “difficult connection / with the girl in the front passenger seat”. Presumably an auto-biographical refraction of his earlier life, the narration describes the topsy-turvy nature of the encounter: “how sky is anywhere, / how blueness jags into the earth”. The narrator’s limited self-knowledge – “I’m twenty, remember. I know nothing” – hints at the possibility that ‘About’ was composed later in the narrator’s life or that it highlights a very self-aware individual, a young man becoming aware of other sexual interests. Later in the poem, the two young heterosexual couples drive to the house owned by the parents of the other couple. The moves and strategies enacted by each of the participants becomes a “chess game”, the “move[s]” creating “surprise”: a “fear of loss”. Yet through the encounter, the male speaker gains the knowledge to trust in the future where “each move’s a ladder, out nowhere, floating”.

David Malouf’s ‘Seven Last Words of the Emperor Hadrian’ invokes Roman history. Hadrian had a close, possibly romantic, relationship with a Greek youth, Antonous, who was thirteen or fourteen at the time. The poem comprises seven stanzas, each one numbered 1 to 7, and each one representing threads in a one-sided conversation, with Hadrian addressing questions to his “little guest” (‘1’), and his “Sweet urchin” (‘4’). Hadrian’s conversation with his “lifelong companion” (‘2’) inevitably becomes angry:

Well let's see how you get on out there without me. Who's kidding who? Without my body, its royal breath and blood to warm you, my hands, my tongue to prove to you what's real, what's not, poor fool, you're nothing.

However, history has the last bitter word with Hadrian concluding, “But O, without you, my sweet nothing, / I’m dust”. Other poems furthering the historical trope include ‘Museums of beautiful art’ by Stephen J Williams, ‘mardi gras’ by joanne burns and the philosophical satire ‘Mind Set’ by Carolyn Gerrish, its narrator pointedly asking, “What is thinking?” and concluding with “we are a sign that is not read”.

There are many poems representing desire, intimacy and care in all there many hues. ‘Ode to Agatha Christie’ by the late Dorothy Porter is written in three six-line stanzas, one three-line stanza, three more sestets, another three-line stanza and ends in another sestet. Of Greek origin, ‘ode’ means a poem to be sung, and the title obviously sings fascination with the famous crime novelist. Detective fiction acts as a background to Porter’s poem in a series of dialogues; the narrator in the first stanza asking, “Is this the crucial clue?” Conversations between life and lifelessness, between “the abysmal depths / of my own life’s mystery” and “every pyrrhic victory” ensue. Differing emotions wax and wane through the stanzas. Descriptive phrases such as “a slippery gypsy” and arresting images like “a belly-up Christie village”. The invocation of Christie and references to her oeuvre inflect a reflective mode. In the fifth sestet, humour emerges, with the narrator evoking Poirot with his “clever egg head” and “waxed moustache”, and the narrator addressing an imagined Agatha about impersonating Poirot. The sixth sestet is pivotal:

But how can I make my solution ship arrive? To what shimmering port will it take me? Or is it just an easy exile from blind faith and wishful talk?

Did Porter write this towards the end of her life? Are there several Dorothy Porters writing the mystery of this ode? I encourage readers to read this elegant exemplar of the ode form and suggest the resolution.

‘Just to Say’ by Dipti Saravanamuttu is a hauntingly-beautiful rendition about absence: “Is there an emotion for missing a shape? / The loss of a silhouette.” The absence invokes a longing for loves’ “shape[s]”, for “the moving shadow” of a former love-subject. After walking “around New York harbour foreshore / at dusk”, and admiring the Statue of Liberty set against the sunset, the narrator faces the future, “the opposite horizon”, and acknowledges the power of love in a memorable moment and “pledge[s] to return”. ‘Coorong Mullets’ by Melbourne-based poet Maria Zajkowski is a recollection of a weekend at Policemans Point in the magical Coorong at the mouth of the Murray River in South Australia. It is organised into three parts: part one consists of one three- and one four-line stanza; part two is two three-line stanzas while part three is four triplets. An economy of language – for example, “in the shallows plovers and stilts pierce the haze” – and striking imagery – “Golden boys run through their blue-eyed summer” – take the reader on a journey through the “hot dusk” of a “Fat Day”. In this elegy written around movement, “the two of us from out of town” return to the caravan park and like “other night creatures thriv[e]” on love in isolation.

Out of the Box: Contemporary Australian Gay and Lesbian Poets is a significant publication, representing the range of poets and poetic styles writing under the descriptors gay and lesbian in Australia at this historical juncture. For poetry lovers specifically and the Australian social formation more generally, the anthology entertains, enriches and enmeshes its readers in the complexities of sexual desire and practice, educating the body politic along the way to never presume any rigid dictum about sexuality.