Mommy Must be a Fountain of Feathers by Kim Hyesoon

Mommy Must be a Fountain of Feathers by Kim Hyesoon

(translated by Don Mee Choi), Action Books, 2008

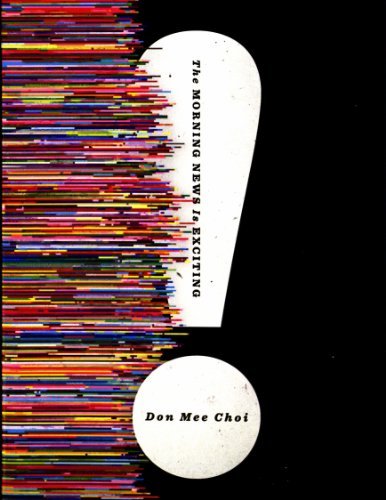

The Morning News is Exciting by Don Mee Choi

Action Books, 2010

It is refreshing to be introduced to a literature through its contemporary women poets. For that reason, I was extremely happy to receive these two titles, both published by Action Books (a small U.S. publisher doing great things). Neither book, though, is entirely Korean. Mommy is a selection of translations into English by Don Mee Choi, while The Morning News is a collection of Choi’s own work originally composed in English.

Choi is a Korean-American poet, and her poetry sits somewhere between the corpus of contemporary Korean and contemporary American poetry. This is something we are familiar with here in Australia. Though South Korea is not technically a colonial outcrop of the West in the East, as Choi points out in her introduction to Mommy, it must be regarded as a kind of neocolony, considering that it houses about 100 US military bases in a land mass a little bigger than Tasmania. Coupled with this, is a heavy economic dependence on the US through structural adjustment loans from the IMF, and ongoing negotiations around the implementation of a Free Trade Agreement, KORUS, which was signed in 2007. Choi makes explicit the connection between her translating Kim into English, and South Korea’s political and cultural subservience to the U.S. In this way she consciously takes on the political burden of all minor literature. Choi never tries to divorce herself from this political operation, in her translations, or in her own poetry.

In connecting the two works, it is tempting to subordinate Choi to Kim. Kim, after all, has published numerous collections of poetry since the early 80s, won multiple awards, and been translated into several languages. For Choi, on the other hand, The Morning News is her first collection. Add to this the clichéd image of the humble translator in the service of the recognised poet, and we start to build a framework of uneven dependence. While it is impossible to argue that Kim’s poetry has had no impact on Choi’s work – a line from Kim appears in Choi’s poem ‘Mirrors Against Logic’ – I think it is more complex and interesting than a one-way process of ‘influence’. The fact is, a lot of writers appear in Choi’s poetry. Weaved into the texts are citations from Foucault, Spivak, Freud, Deleuze, Fanon and Dickinson, to name a few. So while we could quite easily and plausibly make an argument for an explicitly Bloomian relationship between Choi and Kim – pending a quick gender reassignment of the theory – in which Choi struggles against her poetic mother figure, where does that leave Freud, Deleuze, Spivak, and all the other writers cited in Choi’s poetry? We need to work a little harder.

Similarities between the books are plain to see. The first occurs on the level of language use. In her introduction to Mommy, Choi describes mid-20th Century Korean women’s poetry as being characterised by “a language of passivity and contemplation”. Both Kim and Choi violently cut against such a practice: “I tore off my swollen breasts and tossed them / beneath Mother’s foot on the pedal” (from Kim’s ‘The Road to Kimp’o Landfill’), or from Choi: “I would explode if a hot fetus (this is a citation, so I think I should keep her (American/[Korean]) spellings) pressed against my belly” (‘Weaver in Exile’). The body – always female, but resolutely uneroticised – is central for both poets. Central, but not isolated. Rather, the body is conceived by reader and writer alike through its relation to the geographical landscape of Seoul. This leads to a consistent yet divergent quality in the poetics of both writers. Since Kim writes from Seoul, her poetics is impossibly intimate, while Choi, writing from Seattle, displays a poetics of the remote.

In Kim, the body is inextricably and painfully knitted into the industrial landscape. Again, this knitting does not serve an erotic function. Kim’s problem seems to be an optical one: how to distinguish the body from the landscape when there appears to be no clear difference between organic and inorganic bodies. In fact, in Kim’s poetry, organs seem to be largely autonomous from their bodies.

In Kim’s ‘When the Plug Gets Unplugged’, “anyone can look into anyone’s intestines”. In ‘A Hundred Year Old Fox’, a “bloodshot eye opens somewhere deep in the ground”, and a “hot thing” pops out from the womb. On the geographical side, in the ironically titled ‘Seoul, My Oasis’, “the house moves in”. In Kim’s Seoul, organs escape the confines of the body and buildings break free of their foundations. The house across the road rushes in, “reaching our family room”. Eventually, “the houses pile up like stairs and the stairs pile up inside the houses”. While it is tempting to write this off as the personification of an urban landscape, these descriptions go hand in hand with a distinct thingification of organic beings and their components. In ‘The Way to Melodrama 4’, every element forms part of a complete whiteout. “White blanket. White sweat … Jelly fish multiply inside the sea. Sea becomes firm like jelly. White sea. Sea crumbles like white powder”.

There is an irresolvable surfeit to Kim’s poetry, the text is folded in on itself again and again. Things multiply until they subsume that which contains them. The city has fully encroached on the body and the space from within which Kim writes. ‘Seoul, My Oasis’ illustrates the point:

It has been a while since the alley where dogs can shit has disappeared. The corpses that have just breathed their last are suffocated again by the houses rushing in and expire once again. There is no empty land to lay down the coffins. There is no room for shadows in my yard. Stand and hold up the walls.

In this world, even the dead are killed twice. And it is possible because of the way that things fold. There can be an “inside inside inside of a dream”, in which one can lay one’s head on a fluffy pillow on top of “Mommy’s and Mommy’s and Mommy’s ripple”. In ‘When the Plug Gets Unplugged’, toilets overflow even in dreams, though “nothing goes down, no matter how many times you flush.” Organs, organisms, structures and objects all become variable points in a topological cosmos. Topology is, according to Steven Connor’s definition (in his 2002 article ‘Topologies: Michel Serres and the Shapes of Thought’), “the study of the spatial properties of an object that remain invariant under homeomorphic deformation … stretching, squeezing, or folding”. Though the landscape of Kim’s poetry seems to be in continual flux, it does not follow a hierarchical logic of space. In Kim’s poetics, the part is just as likely to subsume the whole, as the whole is to enter into the part. In ‘Asura, Yi Je-Ha, Spring’, Kim writes, “My entire body wants to shoot out of my face”. Objects close in on each other, but end up as yet another interior. Nothing goes down, no matter how many times you flush.

In this topology, darkness governs. But Kim sides with darkness. “Darkness is cozy”, says the rat narrator in the complex political allegory ‘Conservatism of the Rats of Seoul’. “There is no room for shadows in my yard” seems to be a mourning of the darkness of shadows, not of light or visible objects. In ‘Rat’, the darkness becomes something to be protected: “Do people know how much it hurts the darkness when you turn on the light in the middle of the night?” For Kim, the darkness that we might associate with a looming post-industrial metropolis is not dystopian, but associated with “dignity”; it is the darkness in which a “beloved black being” trembles at the penetration of light.

Choi speculates in her introduction that this darkness stems from the patriarchal and authoritarian political and cultural circumstances in South Korea under General Chun Doo Hwan in the 80s. State censorship was profound, and Choi recounts a story in which Kim submitted a work by her now husband, the playwright Yi Kang-baek, to the censors, from which it returned completely blackened except for Yi’s name and the title of the play. It is from this “blackened space”, Choi believes, that Kim Hyesoon’s poetry emerges. It is summed up in Kim’s notion of hyonbin, deriving from hyon as “closed eyes therefore everything is black” and bin as a “signifier for a woman’s reproductive body organs, a mouth of a lock, a valley, a mountain spring … Inside this dark womb the possibility of all life is held. At that place patriarchy, the male centred thing breaks, the universality of all things breaks”. The Morning News seems to me to be written from a similar space of hyonbin, in which the male-centred thing breaks. Choi forces the reader to adjust their eyes to the light in this space. After all, as ‘Weaver in Exile’ asks: “what use are lit lamps, when we are both blind to blackness?”

As I mentioned earlier, Don Mee Choi’s poetry is also organised in some way by its position in relation to Seoul. While Kim’s poetics is marked by an extremely visceral and bodily connection to the city from which she writes, Choi’s poetry stands out for its disparate and complex tension between longing and rebuke for a departed homeland. Choi’s poetics assert their own topologic, in which distance it utterly irremediable. For Choi, “home is a system of longing, and suicide is a system of exile”, and “distance is always far liked tarred breasts”. As such, the bodies that do appear inside of Choi’s distant Seoul are often not her own. In ‘Diary of a Return’, they are women brutalised by American troops as part of their “R & R”. Choi “translate[s] the report of the death of a woman [she] met two months prior”. In this action of translation, she sees herself somehow implicated. To deal with the violence of translation though, Choi does not revert to an idealised or pure form of the lyric. She translates further, weaving in dense threads of theory to make sense of senseless facts. Even documenting a return to Korea, Choi remains distant. “Translation for me is a form of exile. Are & I.”

Each section of The Morning News is followed by a short note on its source texts, though not all sections are as harrowing as ‘Diary of a Return’. In many, Choi’s feminist poetics find more playful outlets. Her ‘Instructions’, based on pre-modern poem songs passed down through the generations to teach correct behaviour to women, are decidedly contemporary and subversive, in which pre-modern rites meets feminist avant-garde:

Call him and call him

like a speaker on high volume

Females are silent

Set the water high and

rise behind the loneliest trees

Tell him you’re here

Claim his wig – it’s yellow

Glow as if you care

Expose his shit right away

Peel his moon if you dare.

“Expose his shit right away” works equally well as advice to young women in their relationships, as to critiquing a male-centred literary culture which classifies literary forms like species of plant life. Choi has an obvious interest in classification, similitude and alterity, as ‘Diary of a Botanist’ evinces. She is an adept botanist of the English language, but her specimens are not filed into an expanding corpus aimed at complete linguistic understanding. Rather, they compromise such a systematic approach.

Choi shows her ear for English through subtle and humorous turns of phrase. “Eucalyptus leaves never rot. How sane” (‘Diary of a Botanist’); “Are you lovely? I am lively” (‘A Journey from Neocolony to Colony’); and “It is one in the morning. Dick talk, dick talk” (‘Diary of a Translator’). Choi makes it clear that she is aware of what she does: “Tell him – my tenses are wrong on purpose” (‘From Noon – To All Surviving Butterflies’). Throughout this fieldwork, classification, language, grammar and imperialism sit side by side. It is expressed most acutely in ‘Notes of a Cowry Girl’:

The formula is: reduced. On June 10, 2006, three detainees at Guantanamo committed suicide. An act of asymmetrical warfare. Some shells are completely white. The technique needs practice. A table for easy conversion will be given. Lastly, don’t despair if things go wrong.

In The Morning News, language’s loaded relationships with empire, discourse, and gender can never be broken, only twisted and subverted.

To this end, both poets frustrate certain tendencies in mainstream Anglophone poetics. Kim’s poetry may grate against English-language readers who expect poetry to be at all times ironically self-aware. Which is not to suggest that Kim’s poetry is in any way naïve; in fact it is erudite and critically engaged (I can’t help but read her ‘Feather is Heavy, What do I do?’ as the most astute parody yet of Bloom’s Anxiety of Influence). But at times it allows itself to be read in an overly allegorical fashion, such as in ‘Conservatism of the rats of Seoul’, or a kind of kitschness, as in the title poem, through the recurrent animal voices and childlike tone, which if read on a single level, seem cringe-worthy. Likewise, a scatological element, or to be more precise, an excruciating corporality to many of the poems, is alien to a lot of contemporary English poetry. The two books together break the male-centred paradigms in a new way. Choi’s poetics may seem more familiar to readers of experimental poetry, but readers seeking a rich and measured lyric are likely to be frustrated by what is at times a difficult, somewhat more detached and hybrid text. Choi never allows English to settle, constantly agitating the political tensions held within it. At once serious and sassy, she constantly “decolonizes/ my forest, my ass”.

Joel Scott is a Sydney-based poet, currently completing a PhD at Macquarie University. Read a selection of translations of Kim Hyesoon’s poems by Don Mee Choi at Poetry International Web.