Watson Era by Nick Whittock

Crater Press, 2016

Whatever happened to the Goddam enlightenment? I understand that this grandiose Western intrigue has moved dialectically through succeeding twilights if not dark ages, and the twentieth century was a sort of apocalyptic culmination or quickening of this protracted ‘event’ with the splitting of the atom, the holocaust and turning the idea of the world into a globalised tele-visual circus of war and business. Maybe we should ditch the old plot of light overcoming dark and go for the Baphomet’s ultimate configurative solution: solve et coagula, come together and go apart.

This is the antagonistic motor of dialectics, the revolutionary (mobile, revolving) intercourse of opposite forces in whose confrontation comes the productive power of the cosmos (thanks, Heraclitus). One living practice of ritual confrontation is cricket, which, like whaling for Herman Melville, functions as Nick Whittock’s system of constitutional metaphorics, the eternal return of contest for the delectation of the gods, and I think the Baphomet an apt figure for the kinds of pagan minstrelsy encountered in Whittock’s new book Watson Era, concentrating conflictual forces in the figure of one charismatic beast.

Like a lot of Whittock’s work, this book is an effort toward the re-enchantment of the world, which does not pretend to universalise its terms but rather acts as a charge for us to do the same. We are presented with the complex symbolic atmosphere of the author’s current obsessions whose structural topoi belong to the spacing of the public but whose relational significance is intensely private. Happily, here, what might seem to be a series of niche obsessions becomes a fierce utopian project of modifying or troping bits of Australia (‘gecko of glory’) to set them in permanent revolution. As an act of constitutionalising the world in a Shelleyean sense, this is not just cheeky but positively anarchistic. I cannot recollect all the proper names gathered here, but I sense that the effort represents an affirmation of human being in all its festive confetti terror – a staging of the life and death drives, of continual coming into being and disappearances, Vulcanic integrations and fiery disintegrations.

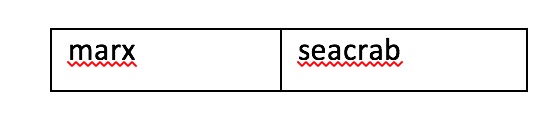

The work proceeds as a series of ritual innings of varying durations, long players and singles in vinylspeak. Much of this ritual action is structured through the intense grid of the cricket scorecard, dramatising the play of the finite as the infinite, the contingent as the necessary. What is made to come together and go apart in this game of signs is just about everything. Whittock’s scorecard method populates the columns of batter, bowler, how out, runs taken, balls faced, maidens, with unexpected values, or proper nouns, or anything at all, and affords the contemplation of catastrophic conjunctions like this:

In all the intricate machinations of Marxist theory, and the way these rhetorical formulae have played out historically in millions of human lives, what is the terrestrial relation of the name, the figure, the phantasm, the radically materialist philosophy of Marx to the seacrab? It is unthinkable, but it compels us to think to the limit. It is also, from the purview of the gods, very funny. Whittock demonstrates with aplomb what poets and I suppose sorcerers have known: comedy can be a weapon (scourge) and a great alleviation (salve) in the recreations of knowledge and the postulation of rejuvenated social systems. This book in particular goes to prove what I had always hoped and expected might be the case: the revolution has to be fun to keep it on a superhuman scale.

Watson Era mixes brilliantly micro and macro structuration, the occasional and the epic (the occasional as the epic), presenting the scale of being from ‘lorikeets’ to ‘gut florikeets.’ ‘James Faulkner’s Fiery Disintegration Machine’ occurs as a series of song cycles that gather their energy centripetally and well as centrifugally, which is to say that they are equally bent on a radical dispersal as well as a radical coming-together of code and combustions of meaning. Among the structural analogues I can think of are the helixical strains of difference and repetition in the oral poetics of Paddy Roe via Stephen Muecke in Gularabulu and in Stuart Cooke’s (polyphonic polymorphic) translations of George Dyungayan’s West Kimberley song cycle Bulu Line. Whittock similarly busts up the colonial aggregation of data by drifting across the regular fencing of the cricket score card. Being mostly hand drawn, these are fairly wonky to begin with (as paddock fencing seems to love to melt over time), but as the poem progresses these aggregate cells are made to swarm and explode all over (and off) the page, with the effect being one of watching a partly controlled particle collision machine.

One aspect of the poem, as I read it, is to capture the moment of being ‘buzzed’ or strafed by a Red-tailed black cockatoo:

black cocka turned tall backs a too-let quiver flame on

like fierce turned upon us back atoo-let fire burn

bright trembling w. un down

quenchable w. un it

desire at great beam of

milky way be for

ever tongue shiftin

This occurs in the context of everything- anthills, gums, boulders, mulgabrush- ‘turning its back on us,’ everything ‘moving’ and ‘shifting.’ This is the bush without its Romantic hero, visually happening at the speed of lexical flicks. The parabola of the event casually hands us infinity, the moment of swooping cockies is exploded to the sublime smudge of ‘milky way be forever.’ This is the star system of cockatoo as celebrity and the milky way as dense ancestral cluster; these things always made of each other, an assurance that is both exhilarating and terrifying, confirmed by the promise to continue making mythos at the end: ‘tongue shiftin.’ I had a ‘bingo’ moment reading and re-reading this poem akin to the heavy electrical experience of seeing Cy Twombly’s Quattro Stagioni for the first time.

- This wicked articulation had become my ‘favourite bit’ of the book for an afternoon, until I went to recover it and found that it did not exist, reading instead ‘Bottlefish Marx possesses.’ I do not regret having become part of the author’s feral compositional method. ↩