Last June I had the pleasure of launching Nick Whittock’s hows its (Inken Publisch) at Gleebooks in Sydney. Since then, Michael Farrell’s extraordinary review has been published in the Sydney Review of Books, and Simon Eales’s essay, ‘‘Get ready for a broken fucken arm’: The anti-instrumentalism of postcolonial cricket poetry’, discussing Whittock’s earlier chapbook covers, has been published by the UK-based magazine Don’t Do It. It seems that we are in a moment – this one, right here – in which a discussion of Whittock’s poetics and a deep engagement with the critical relationship between reading cricket and writing poetry is emerging. In the spirit of the moment, I have reworked, or rather, rewritten, my speech for Cordite Poetry Review.

Years ago I went to a test match at the SCG. Australia versus South Africa. Blazing heat, beer scum smelling of rotten pipes. I sat next to Fred (not his real name), who constructed a large sun-blocker from a cardboard box and a t-shirt, obscuring his whole head. He had a book with him, for slow innings. When I hadn’t heard from him in a while, I looked to my left and found him ferreted in box-shade, reading a chapter of Eric Santner’s On Creaturely Life called ‘The Vicissitudes of Melancholy’. The chapter talks about the writing of W G Sebald, a novelist who, it seems relevant to emphasise, was concerned with the page as a site for the convergence of image, language, history and speculative thought. Fred’s awareness of the game was like a background to something else, an ongoing engagement with the relationship between psychic and creaturely life, or, maybe more exactly, between the problematic of consciousness and the immeasurably large and fraught context on which consciousness depends. The interminability of a January day spent shadeless amongst inaction and stoppage was just one version of this engagement’s endless scenes.

At the time I was making an effort to properly understand the sport, otherwise known to me as a very general sensibility, a set of loose concepts. But learning cricket, as I found out, requires an entire lifetime. Cricket doesn’t just ‘take’ time to learn, or indeed, to play. Cricket is time itself. Cricket is duration made apparent by the logic of industrial time – the rapidity of capital or broadcast modulated by the drag of infrastructural economy (contract, law, language, discipline). Cricket’s massive temporality is what makes it a difficult but compelling subject to dedicate one’s thought to – an act of dedication that is, above all, bound to a history that circumscribes thought’s regulation (in and as the effort of empire, towards a logic of the natural fact). For this reason, engaging with cricket as a critical activity can never radicalise its terms – radicalising cricket would require its literal destruction.

Hows its comprises a series of linked but separate experiments in scoring: scoring a match, scoring for performance, scoring the page, scoring as a register of activity. The experiments write across a body of other texts – literature, philosophy, criticism, art history, politics – and alongside the play of the match. If a game of cricket over-produces its own scoring data, then this book is both homage and satire in its re-staging of the perversity of data proliferation. Scoring a match by anagrammatically hacking Beowulf is no more perverse than the collusion of military technology and KFC to score the game in infrared.

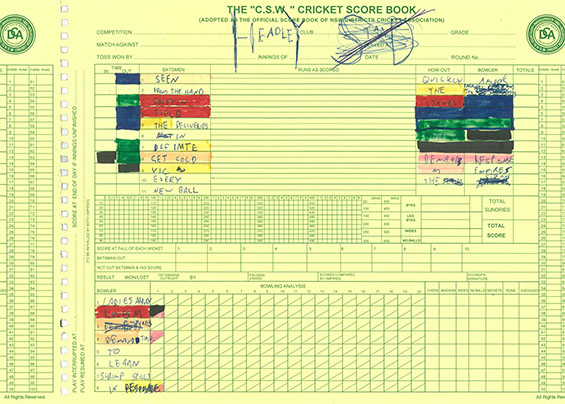

The book is unusually structured, at least, for a book of poems. There’s no system for titles, the colophon is oddly tucked, there are extended spreads of blank, and the scanned pages show the underside of their original overleaf. And it’s as much other things as it is a book of poems; an artist book, a work-on-paper that happens to be perfect-bound but could otherwise appear as a packet of leaves or installed on a wall. Being a book, however, comes with its own consequences, material and otherwise. The object is A4, bound on the short edge, like a clipboard flipped to landscape or the open leaves of a photocopied logbook. This proportion fits snug like a mirror the perforated singles of ‘The “C.W.S.” cricket score book’, a gridded template on which many of the poems are composed. The embeddedness of these different page-forms in the book object draw the reading attention to the construction of a book beyond its most basic function of capturing and facilitating a linear flow. Hows its is also an annotated collection of illustrations – pen portraits composed by Whittock’s sketchy lines, which, though fine, overlay themselves in sudden emphases that make the images somehow both cautious and explicit. These illustrations bring yet another awareness of the hand, a hand whose indexed labour is the book’s total coherency.

Hows its is also map, a work of love, a conspiracy theory about Big Cricket, a sci-fi in which Brian Lara, Michael Clarke and Lara Bingle co-exist as the concept of pure desire, a version of Wittgenstein’s language game played by Ricky Ponting as a melancholy ink sketch and a cyborgian Shane Watson, a list hung together by the promise of numerology or the tease of a code, a meal distributed over a decade, a record of the road between Melbourne and the Brogo Valley, an account of the terminal years of analogue television, a study of the interior of the scanner at the St Kilda Library, a working theory for the logic of a nickname, and a queering of the mythos of sport. Whittock’s labour is not only in the construction of a book that manages to be so much more in addition, but in the capacity to read cricket as a writing practice.

In her essay ‘A Poem is Being Written’, Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick makes a connection between learning poetry by heart (using the regulatory logic of metre as a guide and mnemonic) and being spanked for transgressive behaviour. Both were disciplinary activities aimed at returning her, time and again, to the regular pattern by which meaning and form aligned. One of the reasons she makes this connection, I think, is in order to reconcile the contradictory desires we so often experience in our relationship to literature – the desires to both preserve and ruin it. Too often we are reminded of the inseparability of literature from that which we hope it might liberate us from; too often we are reminded that reading and writing cannot, at least not alone, transform for us what is hopeless. I reread Sedgwick to be reminded that writing does not save us from what we fear, but rather unites us with the fearsomeness of what we desire, allowing that desire to be encountered as a form of thought in what is written. Whittock’s poetics draws a series of radial lines between two acting centres – cricket and poetry, both equally corrupt and equally desirable. Hows its is the double quiver of these two centres, bending into one long duration of attention.