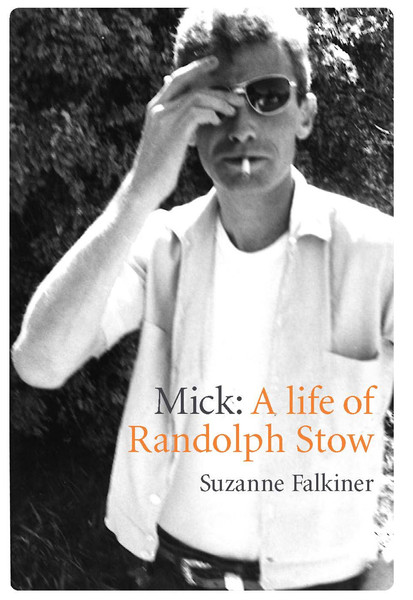

Mick: A Life of Randolph Stow by Suzanne Falkiner

UWA Publishing, 2016

Suzanne Falkiner describes her aim in writing this biography of Randolph Stow as being ‘to contextualise the [literary] works within the broad arc of Stow’s life’. She notes that Stow’s desire for an ‘authorial invisibility – and an accompanying silence – extended to a desire for a chameleon-like camouflage in his personal life’. This camouflage included a retreat from Australia and ‘from the world of published books, in a gradual progression towards silence and into a richer inner landscape’. But, Falkiner shows, this ‘richer’ inner life was always plagued by depression (and one serious suicide attempt), a one-time addiction to prescription drugs, a very complicated (dependency) relationship with alcohol, a fear of madness and a failure to establish long term sexual relationships and to acknowledge and accept his sexuality.

His family always knew Randolph Stow as ‘Mick’ and he continued to use this family name as a pseudonym throughout his adult life. This mask, compartmentalising the private person and public writer, was part of a life-long pattern of establishing a ‘dual identity’. Falkiner shows how Mick ‘continued to present an enigmatic face to visitors … occasionally providing them with a series of polished tropes masquerading as confidences, if not avoiding them altogether’. Mick was a man who both hid behind, and avoided, a number of contradictions.

Falkiner tells us Mick always felt the ‘vile melancholy’ and ‘curse of the Stow [men]’. In him this ‘touch of melancholy’ manifested from early adulthood in the form of binge drinking where his peers often noted that he ‘brooded a lot, he had a need for solitude’; indeed he was ‘uncommunicative except when tipsy’. Falkiner relates how this pattern of behaviour coincided with ‘a struggle with loneliness’ and with a ‘dawning realisation [of] the intensity of his [homosexual] feelings’, but also with an inability to ever ‘overtly come out’.

After a brief, but life-changing period of work in 1957 at the Forrest River Aboriginal Mission, Mick attained an appointment as Cadet Patrol Officer in PNG. This appointment was highly sought after by the then young university graduate so that he could begin a career as an anthropologist, however, Falkiner tells us, ‘cracks were [soon] beginning to appear in Mick’s composure’. The pattern of heavy drinking to deal with the unbearable sense of isolation and loneliness soon manifested in paranoia and crisis (and fear of the accusation of pedophilia) as Mick attempted suicide. Falkiner tells us that there were ‘commonly believed rumours that Stow was homosexual’ among the explanations for Stow’s dramatic air evacuation out of PNG. The fear of 1950s homophobia must have been unbearable.

After moving to England, which Stow claimed was a ‘watershed’ allowing him to ‘write in quite a different way’, he was soon described once again as ‘directionless’ and as ‘drinking heavily’. Cynthia Nolan described him as being in an ‘increasingly fragile state’ as he descended into a new addiction to prescription drugs. Mick admitted to ‘feeling awful nervous sometimes’ as he continued not to write while drinking heavily: on this period in his life Mick reflected, ‘I have been in love, and happily, but for one reason or another have not found a partnership’. When he was finally diagnosed with liver cancer Mick told friends, ‘I’m on the way out … it’s ok, I’ve had enough’.

This feeling that he had always ‘been an outsider’ informed the attitudes that he developed about many aspects of his life. One of his most passionately held convictions concerned the injustices faced by Australia’s First Nations. Mick remembered his own family’s role in the dispossession of Indigenous people in Western Australia. He also knew the racism that was so prevalent in the Geraldton of his childhood. As a young adult, a meeting with the Durack family reawakened his interest in Indigenous justice as he sought a position working at the Forrest River Aboriginal Mission in the Kimberley. Here he would encounter not only first hand evidence of massacres and injustice but also experience of what had so proudly survived: family, culture and language. This knowledge would inform so much of his creative writing: poetry, essays on the Umbali Massacre and his prize-winning novel, To the Islands. Falkiner’s great strength is in contextualising Stow’s writing within the many strands of his life.

Falkiner also explains how Mick’s experience of living alongside Aboriginal people helped him develop particular ideas on the ‘conscious affirmation of the value of black culture … in white Australian literature’. In one 1962 essay Mick described two categories of portraying Aboriginality by Anglo-Australian writers. Firstly there was the Jindyworobak school where the ‘Aborigine represented a symbolic figure, or the past of the country, or white Australia’s collective guilt, or an outcast’. Here Stow discussed the writers Rex Ingamells, Ian Mudie, Judith Wright, Roland Robinson, Eleanor Dark and Patrick White. The second strand dealt with social realism: here Stow dealt with such writers as Mary Durack and Katherine Susannah Pritchard. While both categories had some validity for non-Indigenous writers, their lack of relevance to Aboriginal people led Stow to question, ‘when and how could Aboriginal writers emerge’ to speak for themselves.

Many years later, reflecting on his time at Forrest River Mission, Stow would write that he had been ‘influenced by the “nature mysticism” of the Umbulgurri people, but also by the Quakerism of [some of the Mission teachers]. But in the end I adhered to my own brand of Tao-icized Anglicanism’. Falkiner shows how Stow would continue to develop these ideas throughout his life. In 1966 he wrote his interpretation of twelve of the eighty-one short texts of the Tao, that he called ‘From the Testament of Tourmaline: Variations on Themes of the Tao Teh Ching’. And at the end of his life he wrote that the ‘religious impulse was strong in me but wasn’t satisfied by the C of E God … it made, and still makes, much more sense for me to worship a principle, or process (the Tao) than a personification carrying so much British class and political baggage’.

Falkiner spends much time examining, through the prism of Stow’s life, the many early/mid-Twentieth Century cultural dependencies that existed between Australia and Great Britain. She writes that when Mick began writing, ‘the average Australian found himself in the odd situation of living in two countries at once: the landscape and people around him were Australian, but the country to which his imagination most responded was generally Britain – a state of schizophrenia known rather contemptuously by some Australian writers as second hand Europeanism’. It is within this complicated intellectual environment that Stow began his career as a writer, retreating both literally and symbolically between the two places.