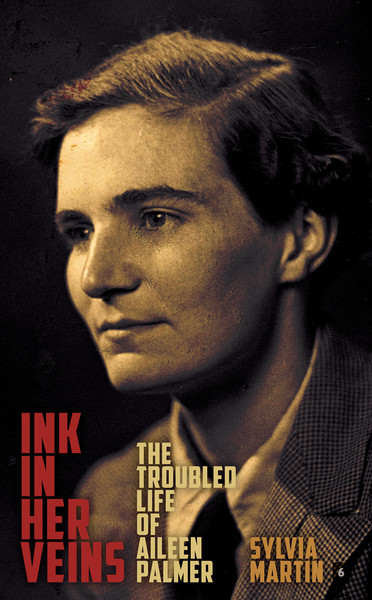

Ink in Her Veins: The Troubled Life of Aileen Palmer by Sylvia Martin

UWA Publishing, 2016

This biography is another powerful testament to the tragedy of difference. Sylvia Martin writes of an idealistic creative pragmatist who was victimised for her gender disphoria and, while loved, never accepted. Aileen Palmer is yet another outspoken and independent woman hounded to the mental hospital and shock treatment.

Palmer was born in 1915 to the dynamic duo of early Australian literature, Vance and Nettie Palmer. And while the Palmers were great supporters of Australian writers, and of their two daughters, they were also very protective and at times overwhelming. The Palmers were progressive politically – being suspected as communist sympathisers – but they were also the products of their Baptist upbringings and devout extended families. Aileen would reflect throughout her life on this stressful juxtaposition between left wing politics and family puritanism.

As a family of writers, the Palmers left a large archive of written material and photographs to the National Library. Sylvia Martin makes excellent use of this resource, quoting extensively from Aileen Palmer’s diaries and creative writings, from childhood onwards, in describing the life and mental health of her subject. This is an astute technique that is as enlightening as it is restorative of Palmer’s public voice.

At age thirteen Palmer was already writing her ‘gloomies’, as she immersed herself in silent films that seemed to advance cross-dressing heroines, and the controversial novel The Well of Loneliness by Radclyffe Hall with its subtle exploration of lesbian themes. Palmer fell in and out love with young female teachers and female school friends, and adopted male dress codes. She wrote a lesbian feminist science fiction play and an autobiographical coming-of-age novel that explored the crisis of her sexual identity and continuing struggles with depression.

In 1932, while a student at Melbourne University, Palmer was driven by idealism to join the Australian Communist Party where she campaigned for the anti-war movement and wrote numerous articles for Proletariat. Her numerous political engagements brought with them a workload that worried her family and friends who would have preferred that Palmer settle for a quiet life as student and writer. But her political activism didn’t detract from her academic achievement as she was also awarded First Class Honours for her thesis on Proust, in French.

Throughout the 1930s and 1940s Palmer lived in Europe, working as a translator and secretary with a medical unit during the Spanish Civil War, and as an ambulance driver in London during the Second World War. This was dangerous work and she lost several close female colleagues. Ironically, it was only during this period of war and trauma, that Palmer would achieve some emotional stability and intimacy in her adult life. War opened opportunities normally reserved for males, and provided some relief from the bullying, homophobic scrutiny of society; now there were other enemies.

After the war Palmer returned home to family, Australia and pressured, unfulfilled promise. Alcohol would become the crutch, giving license to emotional outrage – considered acutely uncivil because of Aileen’s gender – and bouts of severe depression. Martin’s haunting and wretched evocation of this collapse, and her analysis of the sexist censor and treatment that Aileen was subjected to, is remarkable:

It seems incredible today that a young, highly intelligent woman who had suffered a short-term change to her behaviour … could be subjected to nearly three months of such extreme treatment. But Aileen’s breakdown occurred during the period of intense psychiatric experimentation that had burgeoned in the decades after shell-shocked soldiers returned from the battlefields of World War I. Even though what had been previously thought to be a female malady (hysteria) had undergone revision to encompass male war trauma, women still continued to be singled out for deviations from what was considered to be within the ‘normal’ range of feminine behaviour. Aileen’s drinking and aggressive outbursts … her cropped hair, and lack of interest in her clothes and appearance, her lack of interest in the opposite sex, even her intellectual prowess would have been negative factors considered in her diagnosis. And she was not alone.

As Palmer wrote in her own matter-of-fact way:

It would be very inconvenient and undesirable to go happy-mad again, but I’d rather go happy-mad than depressed-mad, as I’m sometimes afraid of going—like I went in 1948-50, off and on. I began happy-mad in 1948, and then couldn’t pick up the threads of ordinary life when I came out of hospital after shock treatment, then had a stretch of being psychoanalysed, which only left me more depressed, so I went in for more shock treatment, then emerged to settle down to work in 1951.

Between 1951 and her death in 1988 there would be many other collapses and periods of hospitalisation, but fortunately also room for work. Aileen would prepare BBC broadcasts on her war service, translate the Vietnamese revolutionary poet, To Huu, and the Prison Diaries of Ho Chi Minh, continue her engagement with such organisations as the Anti-Nuclear Movement and Melbourne Realist Writers’ Group, and complete enough poetry for a 1957 chapbook, Dear Life, and her 1964 collection, World Without Strangers? Today Palmer’s poetry is sadly neglected. She was not included, for example, in the landmark 1975 Mother I’m Rooted: An Anthology of Australian Women Poets edited by Kate Jennings or the 1986 Penguin Book of Australian Women Poets edited by Susan Hampton and Kate Llewellyn, and nor is there any reference to her on the electronic Australian Poetry Library. Palmer’s poetry is very difficult to track down so it is wonderful that Martin quotes several poems in her biography. One of these is the sonnet, ‘In Hospital’. Martin introduces this by quoting Aileen: ‘this is a poem that I wrote, crying, to ease my mind, while I was in there, in jail [hospital], as I felt, but having to accept jail, as better people had been in jail and had found ways of using their time to some purpose’. ‘In Hospital’ reads:

There are more peaceful places – ships perhaps,

whose timbers are well built to take the strain

of dashing winds and waves that wash like rain

on crowded decks and bulwarks … You can see

If now I think of ships it is that here

they leap into mind when, restless still

(though knowing while I have to stay I will

no storm could break me now) I sometimes fear

How ships on other oceans madly dance

like Baudelaire’s hull, tossed on a monstrous sea,

boundless, he thought, or Rimbaud, leaving France –

as though his drunken ship could travel free

Of Europe’s ancient fetters. Let me think

of some frail ships no storm can break nor sink …

For a poem written in 1948 this has a remarkably contemporary feel to it, sparkling with descriptive energy and rhyme while capturing that broken and fragmented emotional state by the use of line division and indentation, ellipsis and brackets.

Martin argues that Palmer ‘regarded poetry to be her serious writing’, and shows how she acknowledged the lead of the ‘Poets of Liberation’: Louis Aragon, John Cornford and Federico Garcia Lorca. Martin notes that ‘she would also identify strongly with the way John Manifold positioned his work as non-bourgeois – vernacular not considered suitable for poetry and writing in the ballad style’. Aileen would celebrate part of this poetic heritage in her poem ‘Remembering Garcia Lorca’, which begins:

You remember the streets with the oranges glowing like suns in the leafy dark of the sidewalks; you remember the streets where the cars were loaded with flowers – requisitioned vehicles daubed white with initials of people’s organisations – F-A-I, C-G-T, U-G-T, representing liberty – And the courage of the dark young men who would take Saragossa, And the myriads of dark eyes, and the music, flamenco, – That was the country of sunlight, the country of Lorca: But the sky was loud with a prelude of German bombers …

One Response to Phillip Hall Reviews Ink in Her Veins: The Troubled Life of Aileen Palmer by Sylvia Martin