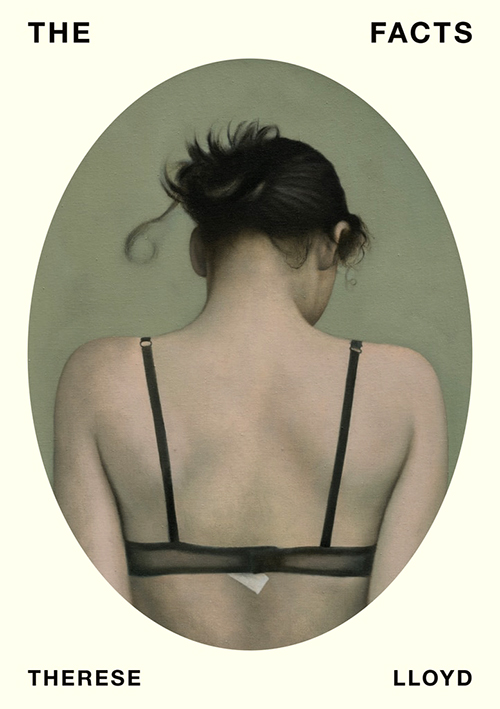

The Facts by Therese Lloyd

Victoria University Press, 2018

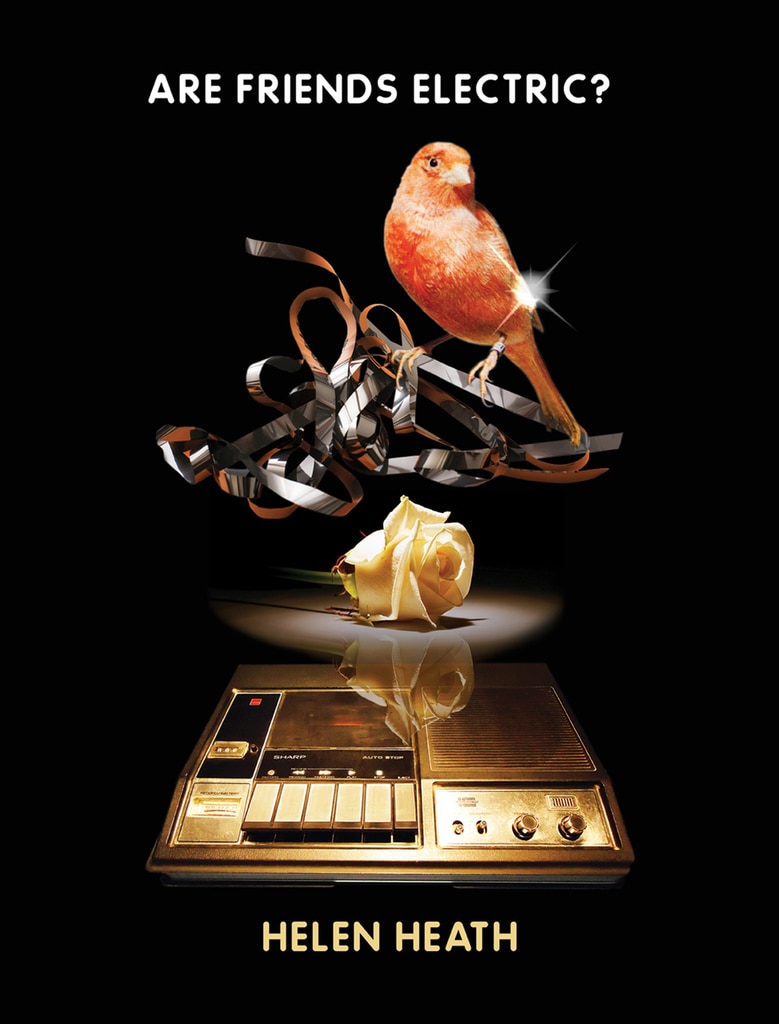

Are Friends Electric? by Helen Heath

Victoria University Press, 2018

Midway through Helen Heath’s Are Friends Electric? I find:

The large electric that is you is like the help that is you and the mouth and the associated kiss.

These lines have come from feeding the collection into an online text randomiser. What sounds and looks like decisions made by a person is the work of a consciousless algorithm capable of capturing a question that charges the whole book: What does it mean to be ‘you’?

There are many resemblances between Heath’s collection and Therese Lloyd’s The Facts. Both were written during doctoral candidature at the International Institute of Modern Letters in Wellington. Both are answering with poetry philosophical questions regarding what it is, feels and means to be human.

Split in two, Heath’s collection speculates about the effect of rapid technological change on humanity: the first section is a succession of testaments spanning from 370 BCE to 2018, polyvocal as the internet itself; the second, an imagined first-person narrative, sci-fi in verse akin to Fleur Adcock’s disturbing sequence, ‘Gas’, and, more recently, Bonny Cassidy’s Final Theory.

Beginning with Socrates’s famous dismissal of writing is wise. Those who rely on the written word will be ‘tiresome company – a reality show having / the show of wisdom without the reality’. Prescient curmudgeon that he seemed to be, Socrates’ worries, Heath proves in this collection, were unfounded. This opening tempers the anxiety that rises (for me, at least) in the face of certain futuristic scenarios; if writing didn’t obliterate our memories, imaginations and selves, then AI may not destroy us either. It is Heath’s own inquisitive, intelligent humanity that energises her poems; the voices of people who have fallen in love with inanimate feats of engineering glow with uncanny familiarity:

I can feel her right now. What we have is real and if it’s only real to me and it’s only real to her then that’s fine.

In the unusual and the extreme, Heath finds not freaks but relations. The Victorian spiritualist attempting to commune with the dead, the robotics engineer creating a third animatronic son, and Heath herself tracing her genetic code back to 1500 — each is simply testing the limits of human life with the available technology.

In the second section, ‘Reprogramming the Human Heart’, Heath gives us the voice of a grieving woman who refuses to accept death as an inevitability. Profound loss is made meaningful with lyricism:

. . . this black night, into which I must send you out in the longboat of your body, seems endless.

If the body is a vessel, then where is the loved self? Following John Locke’s theory of the self depending upon memory, the narrator of this sequence collects ‘enough to build him’ – a digital version of Pygmalion, sculpting Twitter feeds instead of clay into not the ideal but the pre-existent.

An intricate thought experiment, this section considers not only the logical possibility of such a recreation, but the emotional and ethical consequences. In tandem with the robotic reanimation of her deceased husband, the narrator undergoes IVF treatment to conceive his child. This juxtaposition of science that in the last two decades has become conventional with that which still seems hopelessly futuristic is brilliantly perturbing.

As in her debut collection Graft, which was the first non-non-fiction work to be shortlisted for the Royal Society Science Book prize, Heath has shown how lightly and easily poetry can wear serious research.

If Heath’s collection casts an electric brightness over what it means to be human, Lloyd’s is feeling about in the shadows of the self. The epigraph to the first section, titled ‘Time’, invokes Anne Carson: ‘It grows dark as I write now, the clocks have been changed, night/ comes earlier—gathering like a garment.’ The atmosphere does grow dark as Lloyd writes. The opening poem, [to begin], centred on the page, symmetrical as a Rorschach inkblot, signals the psychologically testing quality of the collection. Intended to resemble a moth, the poem adopts the perspective of a trapped specimen, while simultaneously examining it:

the hot glass ceiling reflected only her calm resolute gaze

This double view, from within and outside at once, is maintained to agonising effect throughout the collection. Lloyd’s gaze isn’t just calm and resolute but at times hilariously dry. On the farcical hypocrisy that tends to characterise weddings, Lloyd recalls a meeting between her, her ex-husband and their wedding celebrant, at which the celebrant said in:

a quivery, timid voice that she was in fact, divorced— like a chauffeur owning up to a DIC charge. I was more offended by her sandals.

‘[I]n fact’ is apposite. This collection consists of facts that might be described as confessions due to their personal nature. ‘Confession’ comes from confiteri meaning ‘to acknowledge’, which is to notice and to name. Lloyd does this exceptionally well (to borrow from Plath). There is an art to such revelation; it is not mere exposure of detail but an excavation of the self that requires sharp intertextual instruments. As well as frequently referencing Carson, Lloyd looks to Edward Hopper. In ‘On metaphysical insight’, she writes, ‘The red line of the shop lino blows itself out in a frowning bowl of fruit’, painting herself as she examines Hopper’s ‘Automat’. ‘. . . Hopper liked to think his / paintings weren’t desolate. ‘I’m trying to paint myself,’ he said.’ If the poem is desolate, it is only wryly so. The title’s faux-aggrandisement provides exactly the perspicacity it parodies.

‘What is eros anyway apart from sore backwards?’ Is Lloyd’s understated version of Carson’s conceptual triangle, which defines desire as consisting in equal parts of itself, lack, and the desiring of lack. As she navigates her own experiences of these, Lloyd reads Carson:

something is filling up in her blocking in the surface of the triangle that she’d sooner not have.

It is ambiguous which surface is being referred to: ‘lack’, ‘desire’ or ‘desiring lack’? Lloyd makes the art of lacking look not easy or glamorous, but human – specifically feminine – pulsing with blood and wonder.

In the second section, ‘Desire’, there is a sequence, which particularly hurt to read. This may sound insufficiently academic, but it seems fitting for pain to be mentioned without a footnote in regard to a book whose words are so bodily. ‘What is to be celebrated here? My meat? My fur? I expand outward, and in a fantastic trick of perspective my internals shrink, my vitals no longer vital,’ Lloyd writes with abstruse clarity of pregnancy. A poem later, ‘Imogen’, could be narrated by mother or miscarried baby.

Signs of miracles are important to the faithless stigmata, a vial of moving blood, saints. My little saint suffered via her lungs found it hard to say the word imagine.

Mother, baby, saint and miracle are stirred together in this profound description of lack and desire. In the following poem, Lloyd writes, ‘What do we do when we serve? / Offer little things / as stand-ins for ourselves’, suggesting how oneself can be lacking, either eroded or unavailable.

Just as convincing as her depiction of this lack is Lloyd’s account of a self brimming over. In the title poem, about a noxious relationship, the self is inflated with infatuation. ‘Boundlessness streamed from me like the forever movement / of air. I could feel people breathing me in.’

Earlier in the poem, Lloyd refers to the poet’s medium as air: ‘I breathe and live, nothing more or less’, the words a source of survival. Indeed, this is a work to be inhaled.