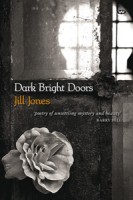

Dark Bright Doors by Jill Jones

Dark Bright Doors by Jill Jones

Wakefield Press, 2010

An intriguing haphazardness is the first thing that strikes you about the language of Jill Jones’s new book. Dark Bright Doors is at once familiar and strange. The tone is highly personal with a slightly highfalutin touch to what seems a study in existentialism. Through a surprising vagueness, Jones encourages us to read her book very deeply. Furthermore, she is asking us to reflect on the reading as we proceed from line to line of each poem rather than from poem to poem. And, yet, as those lines clearly strive to be contemporary and colloquial, the book discusses the loss of individual space in the expanse of information technology and the ensuing isolation and over-exposure in a world where humans are globalised, where there is no place for secrets.

The book is chiefly in the active voice, with a preference for nouns and lists, for phrases rather than sentences, and where those sentences can be found, they may stretch the length of an entire poem (‘All Night, All Night’) or are devoid of sub-clauses. Movement is often suggested primarily by verbs in the present tense and as present participles or qualified by adjectives constructed from present participles; for example, in ‘The Wandering Poem’:

How words graph sky

and fall onto us. Fever dreams.

Doing, leaves, birds. This world.The material empty lights through

in the running, still

or today, world of things.

Washed, curved.Smiling in the haze, water moon.

Crows flying, white, dark.

The laughing unseen, under your feet.

Those simple techniques, whether consciously done or not, give the work the feeling that one of its main aims is to show how difficult it is to achieve prescience in order to win a hidden battle against the absence of a past or a sense of wholeness that is created from stretching into the past rather than spreading into the thinness and brevity of the present. A good example of this focus of the book is ‘The Thought Of an Autobiographical Poem Troubles & Eludes Me’, a search that throws up many associations.

In fact, the very first words of the book, its title Dark Bright Doors, threw up for me as reader links to the Microsoft PowerPoint program stock photo “dark, bright, door”; the U.S. sextet named Dark Dark Dark, noted for its Bob Dylan tones, blues and American folk music (their latest release titled bright bright bright which, apparently, is anything but); contemporary Japanese animation and early 1900s Japan where technology and the loss of Samurai culture were synonymous with the fading of Japanese tradition and a loss of history; and the loss of tradition signaling the loss of history. The constructed rhythm of the lines also reminded me of Steven Wright’s haiku comedy. Even the prose-like poems, such as ‘Let’s Get Lost’ and ‘Leaving It To the Sky’, do not waver from that associative style. The following is a small sample, from ‘Let’s Get Lost,’ ‘Sedition,’ ‘Just Before the Curfew’ and ‘Leaving It To the Sky’:

We want kisses on skyscrapers, something visceral. Let’s get lost, like jokers, a pair of wicked stiffs.

Music is the calm of a bracelet, girdle, helmet

inside words don’t matterbirds

hide in

the window shadowsWastage, control, a single low call rate. You can’t be serious! If you redefine The Problem That Has No Name, would we be here at all? It’s more than the mind-body poser. What will make us think? No-one gets along in the news. I’ve been on most of the rides. Am I my own provocateur?

I blame the fact of the book’s wonderful associative reach on its odd music that so well supports Jones’ subject-matter. In addition to the surprising archaic turn of the language itself at times (for example: “it’s taken you up again in ferment of air” in ‘But to Move’) Dark Bright Doors takes readers through a series of situations and observations which appear to be attempts by the poet to present re-considerations of her place in the world. She seems to want to know if the two – how I think about the world and whatever the world is, something that is never clear – are twinned, reflect each other, influence each other; or are they separate existences merely looking at each other, watching each other grow, change, deteriorate? Answers to those questions proceed to fill the greater part of Jones’s study. Her reply seems to be that we act, we are not acted upon. Her overwhelming concern is with motivations behind actions, the willingness to commit to action and to continue to care to do so; for example, in ‘But to Move’:

You might need an up-to-date glossary,

or something shiny above the wall,

a wing off the sun, blithe in the way

it’s taken you up again in ferment

of air, it’s not pure but it moves.

Though her propositions are mainly argued through a series of statements, they often appear to be questions without the appropriate punctuation. The poems describe arenas that posing such questions give rise to. They create the sense of stumbling around that such questioning requires in its search for answers. It is no surprise that no satisfying replies are really offered. I would say that Dark Bright Doors is a trialing of Jones’s answers, reminiscent of the work of Morgan Jasbincek, Lyn Hejinian and Robert Minhinnick; for example, in ‘Nevertheless’:

Hear that stone in the mouth.

Of death within the other words.Language uttered as bread.

The word for it is dust.

The note of haphazardness arises from each poem being a kind of entrapment of busy-ness, a documentation of emotional and critical cul-de-sacs, snippets of thoughts in an attempt, ultimately, to organise secrets for which there is no protective foil and, therefore, which cannot be maintained as secrets or entirely private experiences; public and private having lost their barriers. However, it is important to keep in mind the wider scope of the study (Jones seems quite clear on this) which is that the presumptions that poetry makes are requirements to seeing how we expand as human beings even as we shrink at the thought of ourselves not progressing. Poetry reminds us how to use our minds properly, how to extend the ether (to borrow a word from quantum physics), how to keep track of that something that holds the physical world together yet ironically confirms that the world, as we think we know it, is only in a fixed state temporarily, that strange something that constitutes us and related worlds. Jones implies that there is nothing else we can really see. Poetry gives structure, the weight-bearing walls to the strange ether, which constitute our desire to live and to communicate with others. Most of all, it comes with learning how to build fords with companions, with others who use a similar language to ours. It is the reward of being of two minds, as it were. Without that doubtful occupation of self-questioning, where would we be? As Jones writes in ‘You Can Only See’:

Pour the light into matter.

What remains, becomes.

You can only see.Land folds along its lines.

Each space not the same as air.What do you need to know

to walk it?You can only see

land unfold

along the lines of its wounds.

In maintaining her defence of her difficult subject, Jones’s success lies perhaps in her patient overall approach. First, she looks at what there is in that subject that is worth her regard; second, why; and, third, now that I’ve bothered to try it, what’s to be done with all that considering-of-things. In that regard, her book reads sometimes as a presentation of points of reference in a study of the world if-only-it-were-not-so-difficult-to-feel-good-about-it. You might expect that, perhaps, the presentation would have been divided into the dark, the bright and the doors. That is not quite the case. The collection seems to be made up of poems from Jones’s dark place, her bright place and her possible answers/doors, where the lines of the seemingly three sets of poems were jumbled together to present perhaps a truer picture of the real world, one where the dark and the bright of our minds are still present even when clear answers banish the depressive and the over-confident. Consider ‘Playing the Interim’:

Envoi

If I close myself, nights become heavier,

uncertain as stars un-resisting gravity.