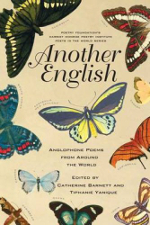

Another English: Anglophone Poems from Around the World

Catherine Barnett and Tiphanie Yanique, eds.

Tupelo Press and the Poetry Foundation, 2014

This anthology’s editors are forthright about its flaws; in their introduction, Catherine Barnett and Tiphanie Yanique admit that their partition of the Anglophone world (excluding the US and UK) into seven parts is ‘woefully inadequate,’ (xiii) and that their decision to concentrate on Ghana, South Africa, Australia, New Zealand, Canada, the Caribbean, and India left out many other regions and nations where English was natively spoken (much of this is simply reflecting the dominant biases of postcolonial study in general). The editors lament leaving out Bangladesh, Papua New Guinea, and the Pacific Islands, but in fact those areas have been widely neglected since postcolonial literature first became trendy a generation ago. Indeed, by incorporating Canadian, Australian, and New Zealander poetry – the first two sections are very much dominated by white writers of Anglo descent – the editors actually buck against the tendency in the US to equate being postcolonial with being a person of colour. Yet the choice of Ghana over Nigeria seems rather arbitrary. I like the national emphasis; we need to remind ourselves that the nations of Africa are sovereign states with varied histories and cultures. That most other anthologies group Ghanaian Nigerian, Ugandan, Sierra Leonan, Kenyan, Zimbabwean poets under one African mantle is both neocolonial and does not acknowledge the sovereignty of African nations. This anthology is just a case, no doubt, of the editors respecting the curator of the Ghana section, Kwame Dawes, and trusting him to make the impressive selection he has made.

The Ghanaian poems range from the lapidary dislocation of Kwadwo Opoku-Agyemang

You guessed it A castle is a dream Without windows (5)

to Kwesi Brew’s adaptation of the garden of Eden story to post-colonial politics:

But that was all before the Revolution. Now he sleeps on a bed of nails; The garden has run to weed And there is no Adam to hail, nor Eve to enquire of … (7)

Ironically, Dawes himself has lived outside Ghana since the age of nine, and indeed is included, as a Jamaican poet, in the Caribbean section of this Another English. Perhaps it takes a certain removal from a nation to see clearly what Timothy Brennan has called ‘the national longing for form’ with respect largely to the Indian novel. While novels have been to some extent identified with nations, poetry has received a broader continental appellation, and it is to the editors’ credit that even in the Caribbean section – arguably a more culturally homogeneous front than the African – there is a distinction made between Guyanese, Jamaican, Trinidadian, St. Lucian, and other poets, even including such small islands as Mustique, a part of St. Vincent and the Grenadines. Not seeing Caribbean poets as defined by nation as much as British or American poets is to, again, disregard a nation’s literary sovereignty, and Barnett and Yanique should be applauded for defying easy talk of diaspora, hybridity, and globalisation to respect the defined space of these poets’ nations of origin.

Dawes’s Ghana section sets up a paradigm that holds reasonably true for most of the other sections of Another English. This is important as, if the book, understandably, has to forsake comprehensiveness, at least what is there should be presented according to a fairly discernible pattern. Dawes thus includes poets known worldwide (Kofi Awoonor, Ama Ata Aidoo, and Kojo Laing, even if the last two are known mainly for their novels) and then mixes them in with lesser-known worldwide voices such as Opoku-Agyemang, Brew, and Abena Busia,. Similarly, in the New Zealander section, curated by Hinemoana Baker, we have a seminal poet of the 20th century like Hone Tuwhare, a senior figure in today’s New Zealand poetry world in Bill Manhire, a writer mainly known as a novelist in Janet Frame, and then lesser known and, in the case of this section, younger (born in the 1960s and 1970s) writers such as Robert Sullivan. Sullivan is represented by one of his finest waka poems, ‘Waka 99’

If waka could be resurrected They wouldn’t just come out From museum doors smashing Glass cases revolving and sliding Doors on their exit … The resurrection will come Out of their blood (167)

While it might have been neat to pair this poem of cultural resurrection with Allen Curnow’s ‘Skeleton of the Great Moa…’ poem, the emphasis of Baker’s selection is vigorous, clanging, and culturally diverse, as in this refreshing demand from Tusiata Avia:

I want my legs as sharp as dogs’ teeth Wild dogs Wild Samoan dogs The mangy kind that bite stranger (195)

Like Sullivan, Avia has no desire to present her (Samoan, in this case) culture to the metropolitan eye: her imaginings are honest, unpretentious, and her own. Anne Kennedy’s ‘I was a feminist in the eighties’ similarly combines the humorous and the feral, and also, like Lynn Davidson’s ‘How to live by the sea’, gives an apt and concise introduction to the imaginative vision of a mid-career poet.

By giving the Australian section over to Les Murray, they asked for both excellence and idiosyncrasy, and they got it. Murray is one of the world’s great poets, and can be granted his prejudices and firm beliefs: though most anthologists would have included John Tranter and Kevin Hart in this section, neither are here. More surprising is the absence of John Kinsella, surely one of the Anglophone world’s vital, nodal presences, and someone who has always kept friendly lines of communication open with Murray. Nonetheless, like Dawes and Baker, Murray gathers outstanding poems, giving us some unforgettable old masters as in Kenneth Slessor’s ‘Five Bells’:

But I hear nothing, nothing...only bells, Five bells, the bumpkin calculus of Time. (152)

I am sure many readers of Cordite Poetry Review all know this poem, but just think of a poetry-loving American or Briton encountering these lines as new: ‘the bumpkin calculus of time.’ Simply unsurpassable.

The Australian section also includes even earlier old-timers such as Mary Gilmore and Lesbia Harford, before moving on to Australians in more or less the equivalent of Manhire’s generation in New Zealand: John Forbes, Peter Goldsworthy, Philip Hodgins, Robert Gray, Jennifer Compton, the first and third Australia lost far too young. The section ends with some poets who have come up in this century. I liked Tom Coverdale’s ‘Woodwind’:

My didjeridoo Nibelunglied Wallows brooding as Wagner's did (161)

One can see why the poet who brought of ‘a rare ear, our aery Yahweh,’ would admire the one who brought off ‘didjeridoo Nibelunglied.’