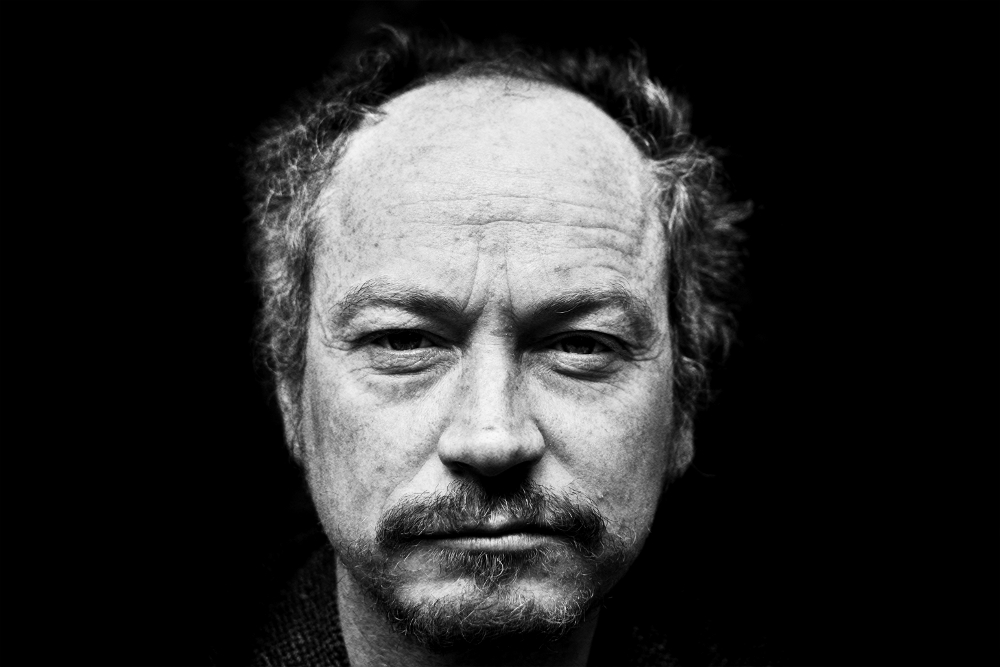

Image of and by Nicholas Walton-Healey

Land Before Lines is a book from Melbourne-based photographer and writer Nicholas Walton-Healey. The 144-page, full-colour volume (the images appear in black and white here for page recall considerations) features portraits of 68 Victorian poets and a single, previously unpublished poem written by each poet in response to their photograph.

Jacinta Le Plastrier: What led you to starting off on this project which, given the complex personalities of so many poets, must have felt like a daunting prospect?

Nicholas Walton-Healey: There wasn’t a single event. For a long time I resisted the idea. It seemed ‘too obvious.’ Before commencing the project, I was spending a lot of time with poets, mainly through my involvement with Rabbit Poetry Journal. I found it really very difficult to be around so many creative, intelligent people without participating in an aesthetic dialogue with them. I mean, although you might be able to go up to a certain poet and say, ‘your work is wonderful because of x, y and z,’ that sort of compliment always means so much more when it’s said in your work.

I studied poetry in the honours year of my first degree. I wrote a thesis on the relationship between the visual and literary arts. If you look at the work of the ‘greatest’ poets, you see a sustained engagement with the work of visual artists. I’ve always been fascinated by that intersection. I know that when I suffered writer’s block, or was in the process of conceptualising a suite of poems or a piece of writing, I often turned to the visual arts or the work of particular visual artists for inspiration. That’s actually how I began taking photographs. So I guess if you really want to trace it back, you could possibly say that the project started here.

Photo of Duncan Hose by Nicholas Walton-Healey

The complexity of the poets’ personalities fascinated me. It was actually the main reason I persisted with the project. But this sort of complexity isn’t specific to poets. What is specific to poets is that their chosen medium of expression is financially unrewarding. Poets can’t sell individual works for thousands of dollars. They can win prizes that are worth lots of money but there isn’t that system of patronage or gallery representation or even the opportunity to forge a living by selling private, independent works. I think this accounts for some of the ‘complexity’ of these people’s personalities. I mean, in the best instances, some of these people are producing work that’s every bit as important as that being produced by the country or state’s leading artists, but because poets don’t get the sort of recognition that artists working in other mediums sometimes receive, something gets twisted. I don’t mean to imply that these people write poetry for recognition or accolade so much as to emphasise how unusual it is to see some of the most accomplished and creative poetic minds living in situations or circumstances that would comparatively be described as poverty.

JLP: How long did the project take to complete, and briefly, tell us how it unfolded and developed? How many images all up do you think you might have taken?

NWH: The project took about eighteen months to complete. All together, I took over 200,000 photographs. That’s not something I’m particularly proud of – it suggests incompetence. But digital photography is all about excess. You get rewarded for keeping the shutter rolling. I think the excessiveness of it makes people relax. They get used to having you continually snap away and so become more likely to let you in on that fraction of a second where they display a side to themselves they wouldn’t normally present to the public. Sometimes people just get bored of having their photo taken and that’s really the best time to go to work.

The project started with Jess Wilkinson, who I happened to be in a relationship with at the time I photographed her. I think her book marionette is incredibly brave and this goes back to what I said before about verbally articulating something to an artist. The greatest compliment you can give them is to make a piece of work that implicitly articulates that compliment.

After that, I started taking photos of some of the other poets we were socialising with. Meanjin got on board around this time and suggested I get a poem from each poet I photographed. They published some of the portraits and poems in one of their issues (these appear in ‘Volume 72, Number 3’). The project really just kept growing from there.

Photo of Myron Lysenko by Nicholas Walton-Healey

JLP: Can you summarise the conceptual intention of the project which is contained in the book’s title, Land Before Lines?

NWH: This project is fundamentally about creative exchange. One of the ways I facilitated this exchange was by asking the poets to nominate a landscape or location where they would like to be photographed. This question compelled the poets to personally invest in the photographic process and made it more difficult for them to complain about the photographs (joke).

I’ve seen so many awful portraits of authors. This is because photographers typically work from the opposite premise; they ascribe to themselves a position of authority. I was very conscious of the fact that the poets I was photographing had far more established and concretised aesthetic convictions than my own, and rather than deny this fact, I elected to work with it.

So this is what the title means. Sure, the ‘land’ obviously refers to the fact that the poets in this book are united by the Victorian landscape and that this unity is privileged over any stylistic or aesthetic ‘lines’ that could be drawn between the poets or their particular use of the poetic line. But Land Before Lines is also a metaphor for a creative sharing that, in this project, is privileged over any division or fencing between photographer and poet. I mean who is actually the photographer and poet? Are the subjects of these photographs even poets? I’m certainly aware that this series of photographs constitutes a portrait of me as much as it does the ‘Victorian poetry community’ or the individual poets presented in the book.

JLP: What your thoughts on ‘auto-ekphrasis’?

NWH: Well, I know that an ekphrastic poem is a poem about a piece of visual artwork that also comments upon its own status as an art object. But I’m unsure of what an ‘auto-ekphrastic’ poem is and I’m not going to waste my time speculating – this is what academics get paid to do.

When I wrote my thesis on the relationship between the literary and visual arts, I used the relationship I perceived between Frank O’Hara’s poetry and Jackson Pollock’s drip paintings as a case study. Those two artists were personally and aesthetically very close (O’Hara even wrote a monograph on Pollock); critics seem to have allowed the distinction between their sexualities to cloud their ability to see the true nature and extent of this relationship. I mean, in order to see this relationship, you really need to get over the emphasis literary critics repeatedly place on the supposed frivolity of O’Hara’s poetry. Although this frivolity is important, especially in the later poems, I think it’s too easy and convenient to just attribute it to O’Hara’s belonging to the second group of artists associated with the New York School (which are supposedly more closely aligned with Pop Art than they are with Abstract Expressionism).

The thing I found most interesting about this relationship was that, when you really start to look into it, there exists numerous O’Hara poems that, although not conforming to the ‘proper’ definition of an ekphrastic poem, demonstrate a very clear relationship with Pollock’s drip paintings. And that’s where I think the power of ekphrastic poetry lies; as an intersection or choice to engage with ideas outside of one’s own medium. This gives the work a greater opportunity of contributing something different to the medium into which these ideas are introduced and I think artists need to engage with ideas that exist outside the formalist constraints of their own medium. Critics got that so wrong about Pollock; I mean Clement Greenberg defining Abstract Expressionism in terms of it being about the formalist qualities of painting. There’s a whole social and political context there that he’s just ignoring. Pollock’s work was very political but political in the only way political art can be – political art cannot be didactic. Similar criticisms were of course made of O’Hara’s work; that his refusal to follow poets associated with specific liberationist movements meant there was a lack of a political engagement. But this was precisely the reason O’Hara had an ambivalent relationship to the avant-garde.

Photo of Nathan Curnow by Nicholas Walton-Healey