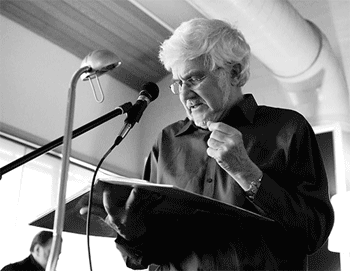

Geoff Page with Simon Milman at The Loft in Canberra, 17 June, 2012

How do jazz and poetry talk to each other? Of course, they can lament their shared marginality to the majority culture – but that will take us only so far. They can boast of their heroic figures over a century (jazz) or the millennia (poetry). They can hyperventilate about the talents of the latest prodigies in either form, but that will almost always be ahead of the facts.

What is it really that they have in common? Can they ever be effectively combined? At first glance, the difficulties seem insuperable. Poetry is the art of the ‘best words in the best order’ (among a myriad of other definitions). Poetry deals in perfection and finality (though Auden rightly pointed out that ‘a poem is never finished – it is only abandoned’). Poetry is not analogous to jazz; it’s much more akin to classical music, where a piece is composed over several months (or years), revised thoroughly and then performed – in most cases by someone other than the composer. There will be different interpretations of what the composer’s performance markings mean in relation to tempi, dynamics and so on but, like a published poem, the piece is ‘finished’ and allows for no (or almost no) improvisation – though earlier centuries’ concertos did sometimes call for an improvised cadenza. And Bach, himself was held to be an outstanding improviser.

Jazz, on the other hand (as everyone knows) is improvised – though that crucial dimension can sometimes be overstated. Not all of a typical jazz performance involves improvisation. The ‘head’ on either side of the improvised solos, though often memorised, is nearly always written down first, as are the complex arrangements for big bands. There are very few professional jazz musicians today (especially among the young) who are not fluent sight-readers. The point remains, however, that improvisation is at the centre of the art form and this is surely not the case with poetry. Unlike the poet or the classical composer, the jazz improviser can’t go back and ‘get it right’. It has to be ‘right’ the first time – and, if not, there have to be subsequent notes that will make it appear ‘right’ in retrospect.

Of course, as with the great composers, this ‘getting it right’ is an individual thing and it is here that a second important aspect of jazz becomes relevant, its sense of tradition – a dimension that it shares, of course, with poetry. Improvisation (and poetry writing) is a deeply personal thing, even though it’s being done in the context of a tradition comprising many earlier “deeply personal” players (or poets). Obviously, artists in either form will influence each other greatly within their own tradition – down through time and/or across time in any given period.

The great trumpeter, Miles Davis, was once asked in this context to summarise the history of jazz. ‘That’s easy,’ he said, ‘Four words: Louis Armstrong, Charlie Parker.’ Of course, one wants to intervene and say, ‘What about Duke Ellington? Dizzy Gillespie? What about Miles himself?’ but one can see the point.

Jazz, as a recorded tradition, is just under 100 years old. We can still see the history of it clearly. Some might want to confine that narrative to 40 years only (say, 1925 to 1965). Certainly there’s not much in the music today that can’t trace its origins back directly to somewhere in that period.

Like poetic traditions (in any language), the jazz tradition is defined by its major figures – those who, in some way have changed either the direction of the music as a whole or have changed how their instrument is played. It’s this tradition of major players that has defined the idiom. T.S. Eliot’s famous 1919 essay, ‘Tradition and the Individual Talent’, makes something of the same point about poetry. As current poets of distinction are added to the tradition, readers are forced to see the earlier ones in a new light. Eliot himself, both in his poetry and his criticism, forced us to see John Donne, for example, in a very different way from how the Romantics saw him (if they noticed him at all).

So what happens, we might ask, when we combine these two art forms with their significant similarities (the importance of tradition and a love of rhythm) and their profound differences (strict performance of a pre-existing score versus the extensive use of improvisation)?

The history of such collaborations goes back at least to attempts in the late 1940s and the 1950s by the American Beat poets to collaborate with the modern jazz musicians they admired. Not all of this activity was documented – but a 1958 recording by Jack Kerouac reading his Blues and Haikus poems with tenor saxophonists Zoot Sims and Al Cohn gives us some idea. After each of Kerouac’s short, often-sardonic poems the tenor saxophonists take it in turn to offer a few bars of musical comment on what they’ve just heard. A poem about a cat walking on ice, for instance, brings a playful staccato phrase to follow it and so on.

Occasionally, the trend towards collaboration became more theoretical – as in a 1957 essay by Kenneth Rexroth where he compared the (surely very different?) work of Dylan Thomas and Charlie Parker. Rexroth noted they were both ‘very fluent’ but failed to see how much revision Thomas put into his poems, mistaking perhaps their sometimes semi-surrealistic images for the spontaneity of an improviser. Along with the then new breed of Abstract Expressionist painters, Rexroth conflated them all as Existentialist heroes.