I grew up in Brisbane where the sticky weather of a summer day resembles something like a bell curve. Predictably cool in the early morning but the sun rapidly burns this away so that by 9am it’s already quite hot. At midday it is hottest (and given there’s no daylight savings there are no hi-jinks) and from there the warmth lingers in the street and the structures. The air, though humid, will gradually cool as the afternoon comes on, perhaps with a westerly breeze offering a little respite in the evening (that is if there is no booming afternoon tropical storm to mark a transition to a cooler late afternoon).

I’ve been living in Melbourne for nearly ten years now. The city’s unpredictable weather is famous, but it’s the preternatural Melbourne summer late changes that I want to draw attention to. Melbourne’s summer heat is sleepy, it holds off after first light so that, at times, just before noon, when the day is still trapped in a chill, you’re lulled into the thinking that the heady-hot forecast was skewed. But the heat of summer builds and builds well past noon to a maximum in the late afternoon (and sometimes late evening). Coming from Brisbane, even all those years ago, I’m still taken by surprise – it’ll be 5pm and just fizzing with heat and still getting hotter, and yet I have a jumper in my backpack.

Now and then, though, you’re offered what’s called ‘the cool change’ or ‘late change’ or ‘late cool change.’ It’s uncanny, and glorious, and has to be experienced to be believed. It comes usually in the afternoon, is a kink in the day’s whole plan, and sometimes marks the end of a string of unbearable hot summer days.

The late cool change begins with a rumour followed by a formal report of it moving over from the west. Geelong will get it first, and then it sweeps towards the outer fringes of the western suburbs. When it arrives it comes seemingly in one hand – a very strong gust of wind, and the temperature drops 10 degrees in that moment, the flourish in a signature, swept to a new weather. To say it ‘drops’ is misleading, too – no weather app can quite capture it. The new weather is stitched into the first gust. There is no decent, it just arrives.

In another weather altogether, last year, and just ahead of the East Coast blizzard of that winter (you may remember it, it actually made news in Australia) I was sitting in the Beinecke Library, New Haven, sifting through the unshuffled pack of cards that is the Barbara Guest archive. For days I moved through as many of the caramel-coloured archive boxes as I could, searching out drafts of poems amongst the letters and photos and collaborative artworks. I’m writing about the visual art processes – painterly, sculptural, collage-like – in Guest’s drafts, for a doctorate at Writing and Society Research Centre, WSU. I’m looking to interpret the bold use of page-space in her later work.

This focus of this article, though, is somewhat of an aside to that research. I came across a few fascinating idiosyncrasies in Guest’s drafting process, including some stunning, very late changes to some of her most significant poems.

Take her poem ‘Roses’, one of her most well known poems, a confident mini-thesis on her favourite word, the centre of her aesthetic, ‘air’…

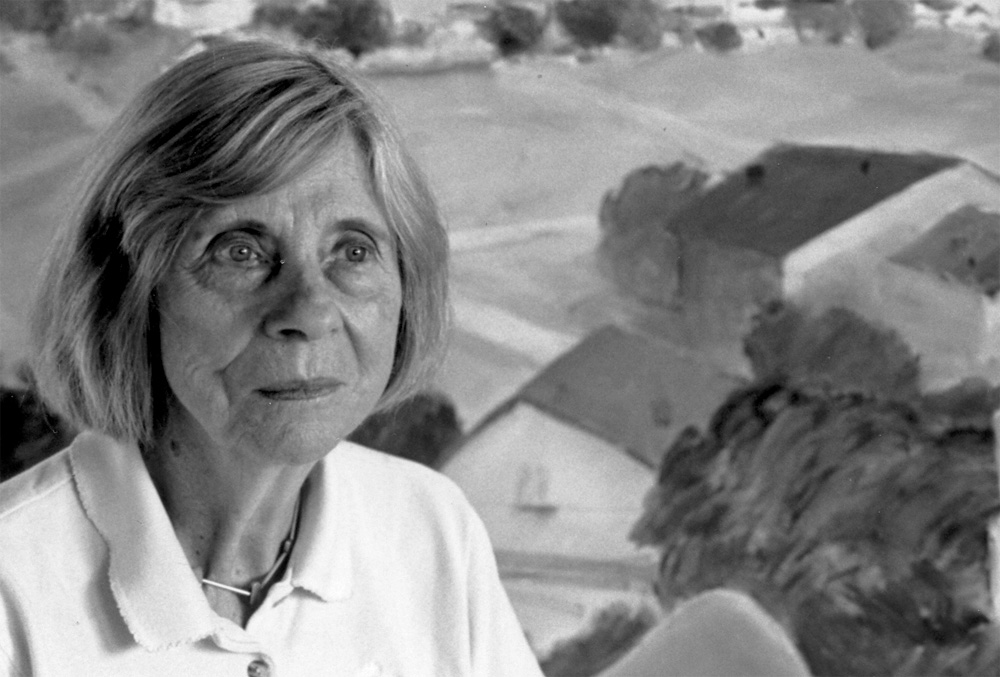

Before I elaborate on the late change to ‘Roses’, and speaking of weather, Barbara Guest (1920-2006), ‘The Fifth Point of a Star,’ as Sara Lundquist (2001) called her, a star representing the first wave New York School poets (with John Ashbery, Frank O’Hara, James Schuyler and Kenneth Koch), was obsessed with air. There is ‘air’ all through the poems of her first five full poetry collections, including the first poem of her first book (1960), the titular The Location of Things – ‘wandering as I am into clouds and air.’ She snuck it into the title of her second book, The Blue Stairs (1968), my underlining, and let it float like skywriting on the cover of her only novel Seeking Air (1978). She then took a long break from poetry to research and write Herself Defined (1984), a biography of the poet H.D. Following this, her poetics, always developing, shape-shifted dramatically and opened out formally and conceptually as the word ‘air’ was replaced by space or the page surrounding the text. All this is to introduce Guest and her interest in ‘air’ a word used often in relation to her two other obsessions: painting and weather.

‘Roses’ was published in her 1973 collection Moscow Mansions. It begins with a quote from Gertrude Stein ‘painting has no air …’ Clearly this caused an irritation in Guest, plunging her into an extraordinary response …

At Poetry Foundation you can read the final poem, and hear Guest reading it.

For an excellent discussion and dissection of the poem, go to a PoemTalk podcast, ‘Air for Roses’, in Jacket2.

In the Barbara Guest archive I found the following: which looks like a very late, almost-final typed-up draft. The epigraph is there, and the poem is nearly identical to the final published poem, other than where I’ve underlined. The last seven lines of the poem read:

The roses of Juan Gris from which we learn the selflessness of roses existing perpetually without air, the lid being down, so to speak, withal a 1912 fragrance sifting to the left corner where we read “La Merveille” and go to sleep.

The corresponding lines of the final poem, published in Moscow Mansions, and her Selected Poems (1995) and Collected Poems (2008) are as follows:

The roses of Juan Gris from which we learn the selflessness of roses existing perpetually without air, the lid being down, so to speak, a 1912 fragrance sifting to the left corner where we read “La Merveille” and escape.

There are only a couple of minor shifts: the antiquated word ‘withal’ has been removed1. Also, instead of ‘and escape’, the last line of the final draft, we have the somewhat more somnambulistic ‘and go to sleep’.

- Fascinatingly, in 1984 (ten years after the poem was published) in a studio recording of poems from 1960 – 1979, Guest, reading ‘Roses’, returned to the word ‘withal’. The new ending ‘escape’ remains, but ‘withal’ drops back in. There is a lovely whisk of breeze caused by the ‘w’ and the ‘th’ in the word, which I think Guest must have preferred. But, as you’ll notice in the 1984 reading, ‘withal’ seems to stick out a little, for better or worse. Her poems are and are not, it seems, like a shoe, ‘which never floats and is stationary’. ↩