Australia’s foundational injustice being the genocide and dispossession of First Nations people means that for many non-Indigenous Australian poets with progressive political inclinations, the country’s racism and colonial violence are necessary targets for their own protest. This is the ‘moment’, hundreds of years long and with wide-ranging impacts, to which much Australian protest poetry responds. For example, Judith Wright, who has been called “the conscience of the nation”, wrote extensively on Aboriginal land rights as well as environmental and social justice issues. Bruce Dawe, “Australia’s anti-war poet”, similarly wrote much in protest of the mistreatment of First Nations people, as well as environmental degradation. More recently, John Kinsella, has written protest poems (he uses the term “activist poems”) across the spectrum of social and environmental justice issues, frequently explicitly protesting colonial violences but always taking seriously the implications of his position as a settler on unceded Aboriginal land.

Like all ‘moments’, those to which Australian protest poetry responds are interconnected: colonialism, racism and xenophobia, environmental degradation, sexism, anti-LGBTQIA+ sentiment, class inequality, disability justice. They are long moments, and changing. They intersect and entangle, creating new conditions to object to, new iterations of inequality, grounded in the same moral wrongs. Jeanine Leane’s ‘O Australia’ not only gestures to Gilbert’s ‘New True Anthem’ with its refrain of ‘Australia oh Australia’, both of them riffing off the national(ist) myth-making language of the anthem, but protests many of the same, ongoing, injustices:

Australia oh Australia you could stand proud and free we weep in bitter anguish at your hate and tyranny the scarred black bodies writhing humanity locked in chains land theft and racial murder you boast on of your gains in woodchip and uranium the anguished death you spread will leave the children of the land a heritage that’s dead (from ‘New True Anthem’)

O Australia I want to […] get the Black velvet out of your closet/ dig deep down under where the bodies are buried/ stitch up your open-cut mines/ Australia you are sick at heart my Country/ Australia we watch our people die/ Australia you are a poor fellow my Country/ what you hid is surfacing/ what you beat is defending itself/ what you scorched is burning you/ Australia there are Countries screaming under your nation/ what you killed is haunting you/ what you silenced is talking up at you/ Australia listen to your ghosts/ hear that terror still nulling you/ Australia what you buried is rising/ Australia you killed your first-born/ Australia you are not young and free… (from ‘O Australia’)

Similarly, when Omar Sakr writes, “It is not this poem / That paid for the blast, but another,” in his 2024 poem ‘Writing poems in the genocide’, he is in conversation with June Jordan, who took similar responsibility in 2005. In her poem ‘Apologies to All the People in Lebanon’, Jordan writes, “Yes, I did know it was the money I earned as a poet that / paid / for the bombs and the planes and the tanks / that they use to massacre your family.” Both poets are speaking about the same thing – namely, Israeli violence against Palestinians, and, more intimately: the authors’ personal implication in it. Moments linger. Moments return. Moments fold into moments: Hasib Hourani’s award-winning debut collection, rock flight, which came out in September 2024, is not only a laceration of Israeli occupation and apartheid but a defiant call to action against it. Like ‘If I Must Die’, rock flight was not written about the moment of the current Gaza genocide specifically, but, released a year into it, the collection is inextricable from what is happening in Gaza and protests it as well.

There are other poems, of course, written in response to specific moments that have in fact passed, but which nonetheless echo across time and space. Dawe’s ‘Homecoming’, protesting the Vietnam war was just as salient when Australia joined the ‘Coalition of the Willing’ to invade Iraq and will be just as salient should the country go to war again. Oodgeroo’s ‘Assimilation—No!’ protesting Australia’s 1937 assimilation policy speaks beyond the country’s borders to make the same case in, for example, Xinjiang where the Uyghur minority are being brutally acculturated into dominant Han culture through prohibitions against practicing their faith and ‘re-education camps’:

We are different hearts and minds In a different body. Do not ask of us To be deserters, to disown our mother, To change the unchangeable. The gum cannot be trained into an oak.

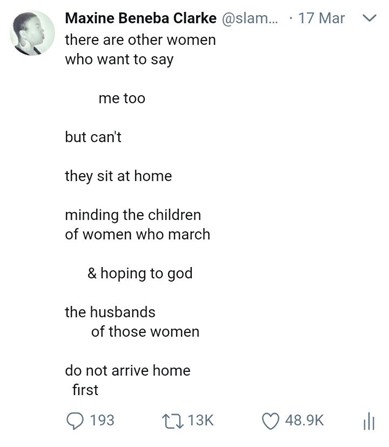

Relatedly, Maxine Beneba Clarke’s poem protesting the erasure of Women of Colour and working-class women within the #MeToo movement, which was written in direct response to it and posted to Twitter, has perennial effect, speaking, as it does, across movements/moments to the conditions of possibility underlying much contemporary feminist organising:

This is what makes protest poetry, at its best, both affective and effective: not only that its gaze is direct and its style lucid, but that it is specific enough to be tangible, to be material, while resisting confinement to its moments or its specific conditions. It allows itself, to return to Kinsella again, to be “recovered, recontextualised, and brought back to act anew,” which is to say: it offers itself as a liberatory tool across struggles. Do not mistake me: this essay will not take a suddenly optimistic turn. As Palestinian-American poet George Abraham notes, “Poetry can’t stop a bullet. Poetry won’t free a prisoner. And that’s why we need to do the political organizing work as well.” Poetry, on its own, is not enough. It is a liberatory tool, yes, but it is necessarily one of many.

That poetry can (to complete Auden’s thought) “survive” and be “a way of happening, a mouth” is indisputable. Similarly indisputable, to me at least, is that it can do more than that, though I’m less certain of what that means in the face of a world so resistant to moral imperatives. What I do know is that uncertainty is not the same as pessimism, and what both protest and poetry require is a steadfastness and determination that run counter to cynicism or hopelessness. I know, too, that we are living in the long durée of revolutionary movement – that the world has been changed and that it is eminently changeable, that we must keep trying to change it. This is not a matter of optimism, but one of resolve.