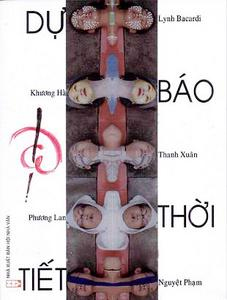

Cover of poetry collection Dự báo phi thời tiết (Writer’s Association Publishing House, 2006)

A narrative seeming the utmost personal and minor in ‘Two moonly ones in the nude’ by Trần Minh Quân – one of the founders of the aforementioned feminist group Nguyễn Trần Khuyên – carries the touch of a fresh discovery of the female body. Fallen drops of blood and the sound of dripping, two naked bodies weaken, but remain teeming with vitality of the imagination:

Two moonly ones in the nude Pre-period arrival, the blood clots my mind two of us lie naked and listen to the tub’s drip to answer the question of a moldy damp morning: Yes, her body is motion. It clung to the chance when I slipped to grasp my hand longer than politeness permits with the message of a craving to kiss my clothes (as they cover my body). From behind the lady breathes question marks into my ear, though the only thing I could then comprehend was the distance between my hands and her lips. Yes, her entire body a dislocated craving, eyes nose, hand leg, the scent of cigarettes the lady smoked – flying high then clinging to me.1

With her own inspiration, unoccupied with bodily hedonism, Lynh Bacardi moves us deeply with a hysterics of mistreatment, the sorrowful ache and grim existence of the body, particularly inside psychological disorders:

By Birth her grace is thirty years old a birthmark at the edge of her left eye I detect the scent of blood on her body the night sky reeks of sewer pipe needles bend beneath the soles of her feet her grace so slowly descends the stairs a visionless gaze a scorching hot road and the shriek of sirens her mother appears murdered in the bedroom hands still holding a mechanical dick blood drips from the stairs her grace is thirty years old

In this poem, the body’s dark secret and the exposure of a libido follow Lynh Bacardi’s cruel language as means of violent protest against oppressive institutions. Impressions of blood on the body, its smell, traces of blood on the stairs, the death of her mother with a sex toy in hand, the needles beneath the soles of her feet – all are signs of the body’s stimulation, dense with urban material, horrifying the reader with a heartless state of inhumanity. This animalistic chaos in daily living space, where those who bear the brunt of suffering, are women. In this place and elsewhere, we hear echoes of Eve Ensler’s The Vagina Monologues2.

To explore instinct, to fuel the needs of the body in writing about love and sexuality, is to become a theme that suits a humanitarian perspective – both as something belonging to people (women in particular) as victims of repressed longing and as those groping in the dark to recover the secrets of their vitality. The passionate instinctual selves of Lê Thị Thấm Vân or Phương Lan exemplify this concentrated strength of sexual impression and emotional intensity. However, there is a political story that seems darker. Consider Lê Thị Thấm Vân’s ‘Freedom’s Cost’, a work about sexuality that does not suggest a passionate attachment and crazy romance. Rather, it evinces something that is vulgar, violent, stressful, exposing the perspective of the victims, as well as challenging us with the tragedies discovered.

Freedom’s Cost The night before I fled by sea mother lit incense mumbling a prayer “God held my child escape … escape police escape imprisonment escape the fish hungry for bait escape the beasts of bronzed faces, square chins, scowling eyes, smacking their lips out on the open sea.” But god goes blind eyed, plugged eared, about-face. A girl of tender age three times suffers nine dicks spit a slimy seed on the vagina-eyes-lips-mouth-hair-ear-belly- thigh-breast… The body of a teenage girl is a delicious feast for the fish under the tender evening light.

Totally explicit and clear in its message, the poem is a testimony of the fate of exiled bodies. Writing in a sense that dredges up scars of hard-won freedom and its expensive cost – I don’t know the past realities experienced by these female immigrant writers – is to accept the trampling of one’s own body. The demand for human rights (freedom) to obstruct women’s rights (sadistic suffering) destabilises the poem between suppressive forces. The final image, the body of a teenage girl becoming a delicious feast for fish under the tender light of a full moon, induces the violent grief surrounding abuse. The literal representation of a woman’s painful experience of crossing the sea in this poem, or the use of a militaristic lexicon as a device to parody wartime language in the previously mentioned poems by Nguyễn Thị Hoàng Bắc, allows the reader to open the subject of feminism up to another subject: a nation’s story. The female-victim condition here can be placed in a genealogy of mythologised images that have transformed Vietnamese women into a people, a nationality, in which they are not only the victims of traditional ideas and social structures as dictated by a patriarchy, but also continue to the be victims who are appropriated to serve a nationalist discourse. The film Surname Viet, Given Name Nam by Trinh T Minh-ha (1989) should be remembered here with its echo of bodies adrift in history.