Image courtesy of Louis Monier / Gamma-Rapho

In mid-August 2016, I was in Adelaide to read poetry with Kent MacCarter and others as a guest of Ken Bolton’s ‘Lee Marvin Readings’ series at the Australian Experimental Art Foundation. Over a couple of days, Kent, Ken and I had some expansive conversations including one about how much we loved various works by Michel Butor, the great French experimental writer. Just over a week later we heard the sad news that Michel Butor had died on 24 August at the age of 89.

Michel Butor liked Australia. He first visited in 1968 as a guest of the Adelaide Writers Festival. In 1971 he made a seven-week lecture tour of Australia and New Zealand and took a week’s break in Central Australia. In 1976, accompanied by his wife Marie-Josèph Mas, he returned for two months as writer-in-residence in the French Department of the University of Queensland. During the residency he researched and compiled the material that would become Letters from the Antipodes.

Although he eschewed overt polemic and psychologising ‘characters’ in his books, in much of his writing the ‘outcast’ was a prominent figure. In Passing Time it was via an encounter with an African worker in a Northern English town, in Mobile, Study for a Representation of the United States, Native American Indians and African Americans, and in Letters from the Antipodes, Indigenous Australians.

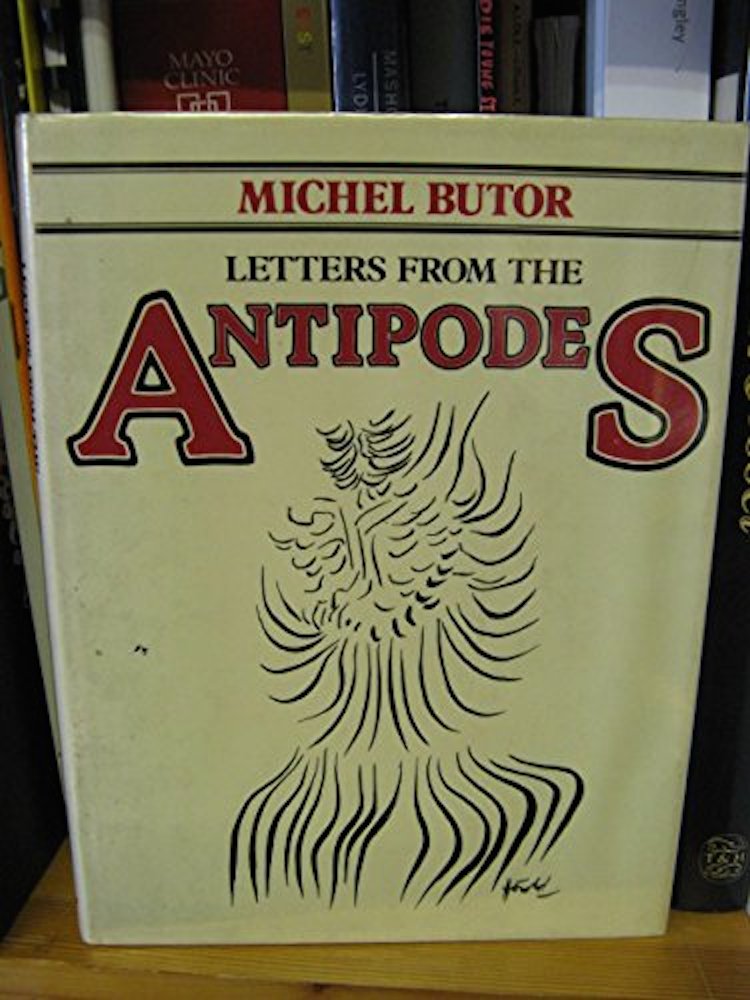

Letters from the Antipodes, introduced and translated by the late Professor of French at Queensland University Michael Spencer, and published by UQP in 1981, is now out-of-print and most certainly in the rare book category. I have a copy that I bought second-hand, but it’s stamped indicating that it was loaned out in 1994 and not returned to a university library or perhaps it was cancelled and culled by the library and sold on. I feel lucky to have it on my bookshelves.

Although he objected to being called a member of the movement, Michel Butor was often associated with the early 60s French literary trend le nouveau roman (the new novel). He broke with the novel form in the 1960s. He said, ‘At some point the novel broke into bits and pieces in my hands.’ After this turn away from narrative towards unpredictable, fragmentary, disruptive experimentation, his readership was reduced and he would sometimes call himself an ‘unknown celebrity’.

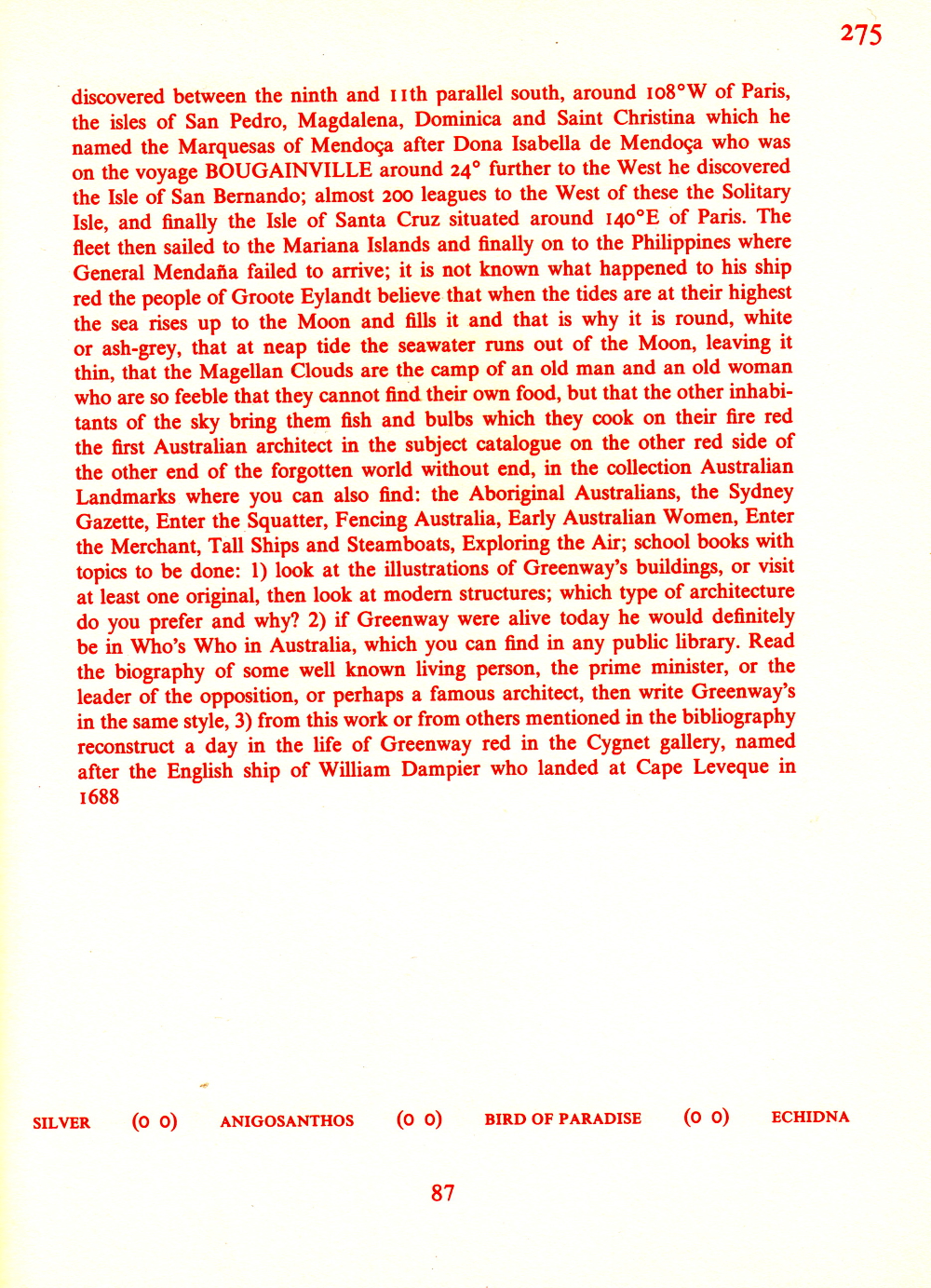

Letters from the Antipodes is a part of a larger work called Boomerang in which each of seven interwoven sections was printed in different coloured typefaces representing various countries. Letters from the Antipodes is in red ink (making it quite difficult to read comfortably). There are running titles at the bottom of each page that locate the content. The structure of the book is complicated. It’s written in a free form, episodic notational style that includes dreams that mark movement from one part to another and often, but not always, when the actual word ‘red’ is used it indicates that the source or subject is moving to a different strand. There are also thematic punctuators like recurring phrases and adjectives.

Butor synthesises or recombines wide-ranging material from ghost stories, from a popular edition of Captain Cook’s journals, descriptions of Aboriginal bark paintings and legends, de Bougainville’s Voyage Around the World, two of Jules Verne’s novels, as well as things like the Sydney phone directory, massage parlour ads and an airline brochure on holiday islands. These comprise ‘strands’ – one relating to Jules Verne is called ‘the ambiguous racism of Uncle Jules’. Butor translated all of this material into French and, according to Michael Spencer, Butor’s translations are often inaccurate, brief and exclude punctuation and conjunctions, thus assisting his notational and elliptical style.

Image from Letters from the Antipodes by Michel Butor, translated from Boomerang with an introduction and afterword by Michael Spencer, courtesy of University of Queensland Press, 1981