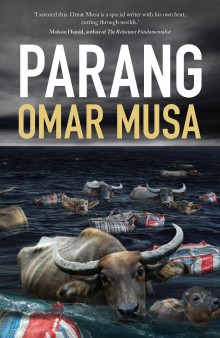

Parang by Omar Musa

Penguin, 2015

Omar Musa is something of a phenomenon. I mean that both in the demotic and the philosophical senses. Self-publisher, author of the successful novel Here Come the Dogs (longlisted for the Miles Franklin), lyricist with international hip hop outfit MoneyKat, Wikipedia subject. As demonstrated by the author photo in this book Parang, autobiographical promotional videos (‘Live and Direct from Kingsley’s Chicken’), comparisons to Junot Diaz and his sartorial style, Musa has made a career from ‘the street’.

Yet he is also from the elite – Canberra Grammar School, private prep school for politician’s boys, is his alma mater. Its old boys include six Rhodes Scholars, Kerry Packer and Gough Whitlam. His writerly image then is a fractal performance, for the public persona is only part of the story, which trades heavily on authenticity and realness. That frisson though is what gives his work energy; however, that dialectic, which is essentially a class conflict, is something we must be mindful of when we read his work.

Parang is a series of short to medium length prose poems. This is not poetry’s poetry, but prose’s poetry – short narratives marked by images and judicious line breaks. There is nothing syncopated or contrapuntal, no great difficulty in finding out the message in this medium. The only layout distinction is the oft-repeated placement of the last third of a poem on the lower half of a second page (once the first page is ‘full’). Other than that it is a straight man talking straight. Musa covers a lot of territory though.

The first section is composed of poems set in Malaysia, his fatherland. There are poems on many themes, including: family (‘Muhammed and Muhammed’ and ‘The Rotten Tooth’); history and the past more generally (‘A trance’); belonging (‘Collapsed Star’); animals and death (‘The Old Rooster’). Close attention is paid to the body and the physical but, thankfully, it is not lyrically saccharine. This is despite giving a good sense of what is happening. It evokes then without being evocative. This is because the work is essentially narrative rather than still portraiture, which means there need be propulsive momentum that could rob a lingering gaze. I found the wry, observant, rhythmic piece ‘Homeland’ to be a standout, but it also typifies some of the problems of an early work, which is evident in this book as a whole. For example, the phrase ‘brown shouldered woman’ is strikingly awkward, and the rhyming is sometimes overdone (sweet air//her hair). From this section though the phrase that resonated most for me though was from ‘The Parang and the Keris’, namely:

or with swish calligraphic

take a head

clean

off.

This is in part to do with the puncturing of the line break and the yoking of writing and violence together. But it is also because of a personal story: in what is now southern Malayasia my uncle’s father was murdered by Japanese soldiers in World War Two. When I was growing up my uncle used to recall how he found his father’s head on a spike not far from their family home when he was a boy, ‘about your age’. My connection to this part of the world, where my mother grew up, made reading the first section of Parang a moving experience. It brought to mind some of my own childhood memories, but what is interesting is how sectioned off Malaysia seems from the rest of this poetic world. Integrating it, like a neo Paul Gilroy, might be the next aesthetic challenge.

Section two has longer poems and is more global (‘Lost Planet’, ‘In Amsterdam’ and ‘Birds on the Bosphorus’) but the voice remains even and consistent. The third section is where Musa’s hip hop influence shows the most (see ‘My Generation’ in particular). It is rhymy, slangy, blingy, conscious. This is not only an observation of Musa’s work though, but also enables the reader to glimpse a symptomatic critique of the fetishised reification of authenticity. Parang is, after all, published by Penguin. No mean feat. Unlikely as it sounds, the urban, trading on realness, is starting to become a more pronounced form of official verse culture here. And that is possible because that is what the market wants, or rather that is what tastemakers perceive the market wants.

Hip hop, which trades most obviously on authentic performance and is the root of this work’s inner beat, is a certain language of the urban that seems at odds with the story of ‘Australia’. We might be a long way from Chris Wallace-Crabbe’s The Australian Nationalists, which analysed the Bulletin debates and the long 1890s decade, but Australian poetry is weighted rural in the contemporary imagination too, from Les Murray to Peter Rose to John Kinsella. Think the Banjo Patterson Bush Ballad Festival rather than the Slam Championship. Parang can be a challenge to that, that can be what it machetes away; not simply because of the identity politics of its author, but also because of the form and style of expression, which after all are never more than an extension of context. Despite being repetitive (which could just be consistency) and sometimes bordering on the banal (which could just be quotidian), and sometimes misperceiving insight for colonial braggadocio (which depends on how one sees the importation of hip hop as lexicon and organising principle), Parang is tight, and for that Musa should be applauded.