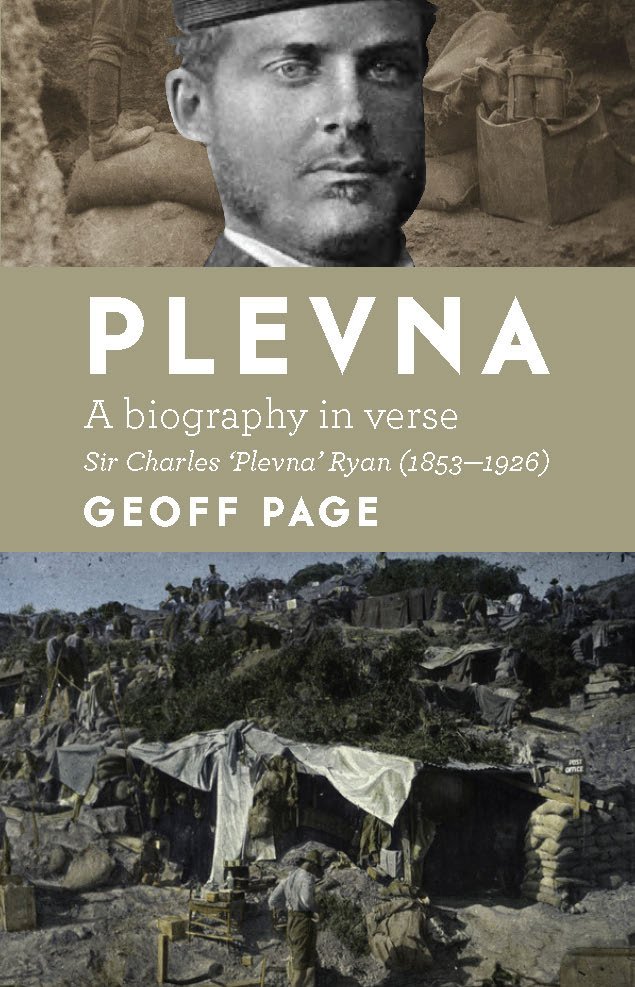

Plevna: A biography in verse by Geoff Page

UWA Publishing, 2016

Geoff Page is a well-known figure in the Australian poetry scene: a prolific writer with over twenty books to his name and an established editor (recently of the 2014 and 2015 Best Australian Poems), yet perhaps known most widely as a reviewer. A regular feather-ruffler, Page’s reviews frequently appear in prominent publications such as the Age and the Australian. Page’s trust in, and loyalty to conventional verse forms is no secret; he often takes aim at more experimental or avant-garde Australian works, as if such attempts to broaden the field of Australian poetics are to be regarded with some suspicion. See, for example, his 2014 post on the Southerly blog ‘Obscurity in Poetry—A Spectrum’, where Page specifically criticises what he calls ‘wilful obscurity’ in the work of ‘a significant group of contemporary (mainly young) Australian poets.’ Or his more recent review in the Sydney Morning Herald of the Australian issue of the American journal Poetry, in which the ‘adventurous but not avant-garde’ is praised, while the work of poets such as Fiona Hile (an award-winning poet, no less) are implied to be ‘outposts’, lacking in substance and complexity. Page’s opinions have challenged more than a few members of the contemporary poetry scene, this author included. Nevertheless, a little healthy sparring keeps all authors on their toes, and given the prominence of Page’s own opinions in Australian media, he is perhaps ready to receive some constructive challenges to his own poetry.

Page’s most recent release, Plevna is a verse biography of Charles Snodgrass Ryan, a Melbourne surgeon and army officer who served in the Turko-Servian and Russo-Turkish wars, then later at Gallipoli. He received the nickname ‘Plevna’ after spending four months in the siege at that city in 1877. From the first poem, Page suggests a reason for his interest in pursuing Ryan as a biographical subject: ‘Why have we no biography, / three hundred pages, dense with footnotes, / boasting your achievements?’ Ryan’s own 1897 book, Under the Red Crescent: Adventures of an English Surgeon with the Turkish Army at Plevna and Erzeroum, 1877-1878, left ‘a vivid whiff’ of his experiences, Page writes, ‘but covers two years only’. There is a sense, then, that Page intends to celebrate a life not yet well celebrated in historical narratives.

Fittingly, Page begins not with his poems, but by using Ryan’s own words from Under the Red Crescent. This opening quotation, in first person, documents Ryan removing the leg of an injured man who refused anaesthetic. There is a hint of humour in the patient’s casual demeanour:

He never said a word, and went on smoking his cigarette all the time … [and] answered all the questions quietly and unconcernedly while I was stitching up the flap of skin over the stump’ [italics in original source].

Page continues to present prose quotations as moments of pause between the poetry sections. Selection and quotation from historical documents are a common feature of documentary poetry, and Page has included passages that titillate in their gruesome and shocking details as Ryan portrays his dealing with injured soldiers: a man suffers a bullet through ‘the upper portion of the brain’ but recovers; another has his head blown ‘clean off’ and after ‘a spirting [sic] from the blood-vessels in the neck … the headless corpse spun around in a circle.’ There are also frequent quotations littered throughout the poems, indicated with quote marks, which increase in frequency as the narrative unfolds. The following passage, for example:

You meet his rather splendid wife, just ‘twenty years of age’, ‘complexion of exquisite fairness’, ‘large blue eyes that looked me frankly in the face’. In eighteen months you haven’t seen a woman anything like this. The Bulgar girls are ‘squat and swarthy’; Armenians are ‘frowsy’; the Turkish girls all ‘veiled in yashmaks’. Your heart is ‘beating’ with ‘delight’.

This method of including source material spoils the flow of the poems a little, and suggests an anxiety on the part of the poet regarding unattributed quotation. Some of the more successful documentary poetry – see, for instance, works by the US poet Susan Howe, Canadian poet Dennis Cooley, or Australian poet Jordie Albiston – will absorb the words of others into the poems as part of the performance of redacting history through the poetic medium. Page has opted to foreground his quotations, and while some of these do offer insights into Ryan’s voice or manner of speaking, a majority of ‘quoted’ phrases, such as ‘twenty years of age’, do not seem justified in their use of the same technique.

Page sets up an interesting dichotomy between Ryan’s first-person, prose passages, and the second-person voice that addresses Ryan in the poems and draws the poet-author into the field of narration. The first poem finds its way to approach Ryan through biographical narrative, with the ‘I’ of the author exposing a ‘maudlin’ desire ‘to address the dead’; and this conceit of direct address continues throughout the book:

Maudlin to address the dead, especially unintroduced, but even so, Charles Ryan, I have the urge to do so, Melbourne surgeon, later Sir, but ‘Charlie’ to your friends. Also known as ‘Plevna’ Ryan but that can wait till later. Your dates are 1853 to 1926, a life as long as mine is now or was when I began.

The decision to use second person is a curious one, perhaps intended as an extended elegiac narrative; the remembrance that Page felt to be lacking. Or, perhaps Page intends to bring an intimacy between the subject and himself, the author of this life story. The approach works well in the initial stages of the narrative, as the poet matches some of grisly medical details to come with his own poetic metaphors. Page ponders the ‘shock’ that a young Ryan at med school must have experienced as a rural-born boy: ‘the way a scalpel slices in / to spill things on a slab / and how a ribcage may be sawn / to offer up its thoughts.’ There are several such moments of speculation, where Page muses in the space where details are missing; this gives us a strong sense of the poet’s attempt to ‘find’ and connect with his subject. This intimacy, however, is soon held back by a persistent tendency to document the facts of what happened at different moments in Ryan’s life in a rather plodding, chronological manner, rather than utilising the complex devices available to the poetic medium to help us understand more intimate details about the man. On this note, it is worth mentioning that Page has adopted an iambic metre for the poetry, which seems apt considering that much of this work is focused on Ryan’s involvement in World War I; the iamb recalls the rhythms of war poems of Wilfred Owen (‘Dulce et Decorum Est’), John McCrae (‘In Flanders Field’) and others. Beyond the promise of the first pages, however, there is a formality to the poems that comes across a bit flat, especially combined with their adherence to linearity and fact.