Collected Poems by Arvind Krishna Mehrotra

Giramondo Publishing, 2016

It can be daunting to survey a poet’s life work: there is the temptation to ‘make sense’ of the work as one coherent picture – to see it steadily developing in one trajectory, or honing one aesthetic (with deviations from this measured and marked) – or else as containing discreet phases which have beginnings and ends. While this impulse can be insightful in the right instance, it can also gloss over a diversity of approaches, corralling aberrant poems into categorical coves. In reviewing the Collected Poems of Arvind Krishna Mehrotra, I have let myself see patterns across time when they occur, without being constrained by expectation – although the array of aesthetics in Mehrotra’s poetry encourages the desire to look for patterns.

This collection presents a substantial body of work by one of India’s most renowned contemporary poets. It includes selections from Mehrotra’s four original poetry collections –Nine Enclosures (1976), Distance in Statute Miles (1982), Middle Earth (1984) and The Transfiguring Places (1998) – along with uncollected poems, a significant number of new ones, and Mehrotra’s translations of old and new Indian verse. The translations make up a quarter of the book, and include ancient Prakrit love poetry; the songs of the fifteenth century iconoclastic Bhakti poet, Kabir; and work by modern and contemporary Indian poets Nirala, Shakti Chattopadhyay, Vinod Kumar Shukla, Pavankumar Jain, and Mangalesh Dabral. The range of the book’s content reflects Mehrotra’s compulsion to dive into anything that interests him – from surrealism and Beat poetry to mystic songs.

The book opens with an author’s note:

Just as some children when they grow up want to become snake charmers or railway engine drivers, I wanted at seventeen when I started writing to become a book. Not any book but a volume in, say, the Arden Shakespeare, or one in the uniform edition in the works of Walter Scott. The latter held particular appeal because it covered from end to end an entire shelf of my uncle’s library, the books standing to attention like a platoon of soldiers in green jackets with gold buttons.

This arresting image offers a twist on the adolescent fantasy of ‘being a writer.’ Mehrotra’s desire to be bookish (a metamorphosis that is both quotidian and fantastic) foreshadows the interactions between self and things in the poems that follow. Such respect for objects – whether book, potato, cell phone, bra, ant, wash basin, the list goes on – is evident across Mehrotra’s poetry. Surrealism is a useful context in which to read the progression of Mehrotra’s work. As he notes, ‘For me who started writing in the 1960s, the discovery of surrealism helped resolve the awful contradictions between the world I wanted to write about, the world of dentists and chemist shops, and the language, English, I wanted to write in.’ Surrealism allowed Mehrotra to accommodate his own reality – in Allahabad, in Uttar Pradesh in the north of India – to English literary language, with its dominant (realist) representational uses, and its associations with British and American landscapes and subjects.

The other context useful for tracking Mehrotra’s trajectory is his keen interest in modern American poetry: ‘the American speech I now heard (in the Penguin Modern Poets 5, published in 1963) seemed closer to our everyday English in Allahabad than anything I’d read before.’ The implication is that both uses of English were fresh, and therefore suited to each other. The influence of modern American poetry is evident from the earliest work presented in the Collected Poems. ‘Ballad of the Black Feringhee’ (in ‘Uncollected Poems 1972-1974’) begins with an epigraph by the American Objectivist poet Carl Rakosi:

I would rather sing folk songs against injustice and sound like ash cans in the early morning or bark like a wolf from the open doorway of a red-hot freight than sit like Chopin on my exquisite ass.

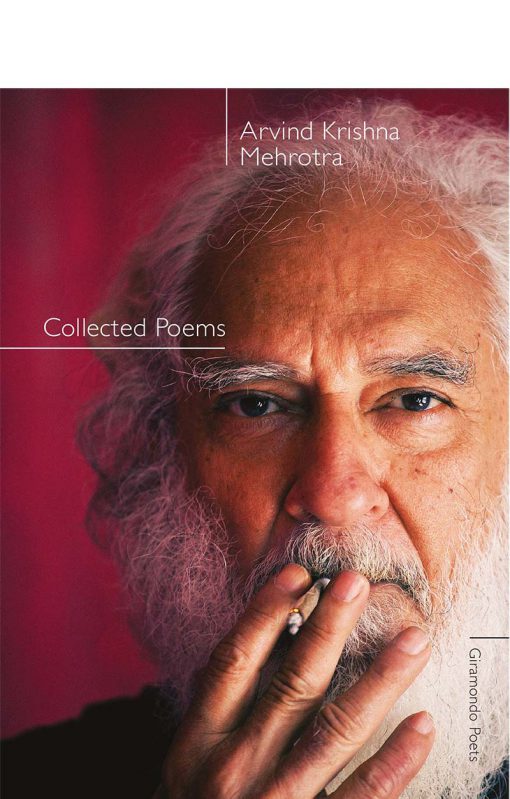

Rakosi’s voice is direct, fierce, and anti-pretention: qualities that appealed to the young Mehrotra. In poems such as ‘On the Death of a Sunday Painter,’ Mehrotra admonishes through satire genteel artists who don’t get their hands dirty, and who remain aloof from their subjects. This is an affectation that Mehrotra is fond of, and that’s also conveyed in the striking cover image of the grey-haired poet inhaling a lit cigarette (the ash at the tip out of focus, the cigarette’s ring of fire burning towards him) while staring directly at the camera lens. The poet’s eyes are clear and hard, suggesting an appraising relationship with the world.

‘Ballad of the Black Feringhee’ is an Indian version of Allen Ginsberg’s ‘America’ (1956). While both poems feature a rambling narrator, Ginsberg’s poem is characterised by its political overtones and anger, in contrast to the quiet melancholy of the former. Feringee is a derogatory term for an outsider in India, particularly one with white skin. A black feringee suggests the archaic use of the term, to mean someone of Indian-Portuguese parentage. The poem is playful in the early and middle sections before melancholy creeps in. The ending combines these moods:

India your police stations are little Siberias India when they come for me I’ll put on a clean shirt […] India there’s no need to hide your large teeth India what a big nose you have India remember the pile of ash on Mandelstam’s left shoulder India don’t destroy yourself in slow motion.

The introduction of fairy tale (Little Red Riding Hood) into the end of this poem about India, inspired by an iconic poem about America, shows the heterogeneity of Mehrotra’s imagination. In these early poems we see the shaping of a voice through the interplay of an American idiom, surrealism, and a visual, object-oriented aesthetic, all carried by a measured yet informal diction. This poetic rucksack (travel is an ever-present theme in the Collected Poems, as I explore below) is capacious enough to hold poetic monologues (‘Songs of the Ganga’, ‘Remarks of an Early Biographer’), tender poems about family (‘Continuities’, Genealogies’, ‘Canticle for my Son’), domestic poems, poems about street life, the occasional villanelle or ballad, and lists.

In the beginning sections of the book, including uncollected work as well as Nine Enclosures and Distance in Statute Miles, startling surrealist images present themselves casually. For instance, ‘I / must … / straighten my eye with a hammer’ in ‘Between Bricks, Madness’, which sees the world of labour as strange and dreamlike:

[…] when a naked man a flat-eyed goat on his back dances upon the steps of sunset

Such lines evoke the great surrealist painters. In ‘Songs of the Ganga,’ the poet tells us, ‘From the leopard [I learn] / how to cover the sun / With spots’. This poem is an interesting case of surrealism working in tandem with Hindu mythology, where the river Ganga (Anglicised as Ganges) is routinely personified as a goddess. The poem begins:

I am Ganga […] I am the plains I am the foothills I carry the wishes of my streams To the sea I am both man and woman

To me the poem critiques western art categories, challenging them to accommodate religious mythology. This poem is representative not only of the surrealist monologue in Mehrotra’s work, but also of the list poem, which can be explained by his way of being in the world: in the Collected we encounter the poet as botanist, taxonomer, geographer, cartographer, mythographer, naming and numbering the things in his environment. We’re shown the poet in action in this mode in ‘Classification,’ which begins with plants – ‘Are trees vertebrate? Spikenards are’ – before moving on to bones.