O Sonata: Rilke Renditions by Chris Edwards

Vagabond Press, 2016

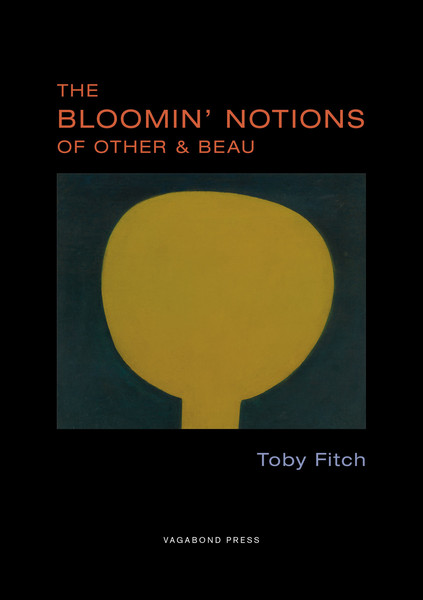

The Bloomin’ Notions of Other & Beau by Toby Fitch

Vagabond Press, 2016

Chris Edwards’s O Sonata dwells in the vortex of the underworld, plumbing the depths of the Orpheus and Eurydice myth and resetting the entrails of Rilke’s Sonnette an Orpheus into a crossword puzzle ready for consumption. In the eponymous sequence, Edwards offers up a renewal of the Orpheus (also known as ‘the futile male’) myth to signal his reconsideration of repetition and originality as the basis of a literary revision – releasing a suite of renditions that purposely misinterpret, transliterate and obscure. Set up as an intertext to Rilke’s original sequence, Edwards’ rendition is animated by forces that teeter precariously on the edge of construction and destruction, or as he makes explicit in his opening poem:

a vortex Turning on the same old Still point – we really tore up That dungeon.

However, well before his ‘long climb from Hades,’ Edwards provides the context from which his poetic revision takes leave:

rendition | rɛnˈdɪʃ(ə)n |

noun

1. a performance or interpretation, especially of a dramatic role or piece

piece of music: a wonderful rendition of ‘Nessun Dorma’.

• a visual representation or production: a pen-and-ink rendition

• of Mars with his sword drawn.

• a translation or transliteration.

2. (also extraordinary rendition) [mass noun] (especially in the US)

the practice of sending a foreign criminal or terror suspect covertly to be

interrogated in a country with less rigorous regulations for the human

treatment of prisoners.

ORIGIN early 17th cent.: from obsolete French, from render ‘give back, render’.

The combination of this definition with Rilke’s original poetics creates an immersive reading of the fluid relationship between repetition and originality. As Julia Kristeva elucidates, ‘each word is an intersection of other words where at least one word can be read’, and in poem 7, Edwards readily deploys this idea:

Bid[s] verboten and adieu. Your best alternative lingers in this here remedy for Turning: Do not default. The remainder’s a black Hole hollering Hey, Frankenstein, halt!

The amalgamatic nature of verboten and adieu are key here. Rather than simply translating the poems – which Edwards, in a podcast for The Red Room Company, argues is ‘not possible’ – he ventriloquises the language of Rilke to the purpose of repetition and ‘malaprop[ism]’; but more on this later. At the same time, the blending of Germanic and French diction does as the antecedent example implores: it does ‘not default’, in fact, the suite of renditions resists traditional translation and semantic form. Throughout these inversions, Edwards has experimented with these terms to the purpose of linguistic innovation and textual challenge. What I mean is, the basis of Edwards’ collection is betwixt and between the impulses that are inherent in Rilke’s myth: a parable not to look back; that which is verboten [forbidden]; and the fragility of mortality which we must remember and to which we must bid adieu [farewell]. Further, Edwards makes it apparent that these terms are rendered meaningless through the implementation of ‘and’, the subject acknowledged fleetingly in verboten before being dismissed in adieu. Such conditions establish Edwards’ consistently disjointed voice within the ‘vortex’ that is O Sonata, rumbling and tearing up expectation, unburdened by narrative curtails and ‘turning on the same old Still point’. In this sense, Edwards’ rendition is a feat of originality, no less original than Rilke’s; the only difference between O Sonata and other texts is that Edwards is acutely aware of his source material, and makes the reader implicitly aware of this.

In poem 2 Edwards acknowledges the futility of translation:

As for that Big Stink we approach – again? – it’s Lies they tell me to fix myself fast to …We’re here, Madam. My chain …

When compared to the corresponding passage in Rilke (1.2):

enfinden noch, eh sich dein Lied verzehrte? – Wo sinkt sie hin aus mir? … Ein Mädchen fast …

It becomes increasingly clear how Edwards’s revision is not based in linguistic meaning; rather, his poetry weighs the silhouette and homophonic possibilities of the word, to weave a mistranslation that systematically disrupts consistent meaning and interpretation. In this way, Edwards oscillates between the construction / destruction imperative I outlined earlier, utilising Rilke’s poems only as a measure for himself and as a springboard for his own journey into language.