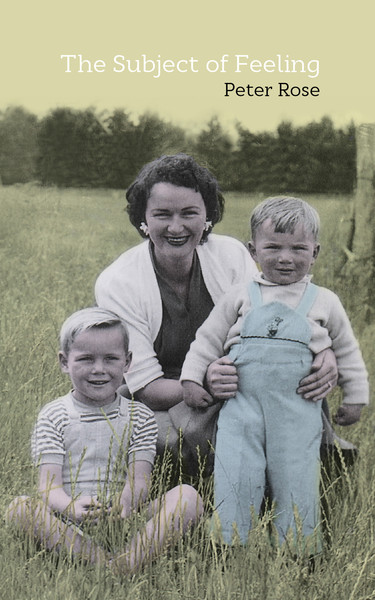

The Subject of Feeling by Peter Rose

UWA Publishing, 2015

From the beginning of the latest work by Peter Rose, the reader is given the impression of an unfolding tableau or score, the creases and outlines of which to be generously shared. A sense of intimacy is engendered from the outset: we are let in on the scales and arpeggios that a musician practises, as if each poem, or note that it reaches, ‘might lead somewhere / or fail to ascend.’ The seemingly off-hand candour of such admission serves as an indication that one is in for a special experience from a master of the craft.

Consistent with the presentation of layers of the self comes a confessional tone touching on the bittersweet recognition of stages of life that are passing or have passed. This is evinced by familiar tropes of hidden childhood treasure, gold and dirt comingled – but also a sense of bemusement, mystification of the ages, such as a ‘Plantagenet cut’ as an almost hallucinatory image in a suburban park. This quasi-historical hallucination is echoed by expression of bewilderment in an art gallery, experiencing ‘something like mystification’ in the flashbacks revealing intensely personal strands that compose the nets of everyday life.

The very elusiveness of inter-personal recognition, in ‘Late Autograph’ and ‘Dux’ indirectly introduce walk-on parts in the work – once again a sense of the intimate, but with a sense of darkening and unease. This sense distils into moments of quiet, reflective beauty in ‘Days and Distance,’ recalling: ‘So many years ago. / Cruel to dislodge them / like moss in a grotto.’ A plane journey works as a vector for an elegiac and concisely rendered return to the past, which evokes the best moments of Bruce Beaver: lives connected to one another by literal and metaphorical roots and threads, which form ‘the ramifications between us,’ inescapable and tropic in their impact. In another poem, with a cherry as aide-memoire, Elizabeth Bishop and ‘all those lines about loneliness,’ makes their appearance to the lost narrator, and culminate in ‘an unexpectedly quick twilight.’ Impermanence and sliding scales of reality mark the first section as the initial scores of a composition, where notes are left visible even if unplayed, and what is unsaid resonates with a force equivalent to the words left on the page.

The ghostly presence of precursors, familial and famous, and a premonition of the book’s central event, a death in the family in a car crash, as the children chant in memory of Marilyn Monroe, shows a certain menace, a darkness close to home: ‘The Hume relentlessly narrowing, / a blur.’ and his father’s ‘terrifying’, if ‘brilliant,’ way of handling the wheel. The ‘old ones,’ as the epigraph from Donald Justice to ‘The Elders’ makes clear, are not about to let go. They demand their space in the realm of the living, and the present is pushed out to its limits with the resultant psychic friction. As the deceptively simple ‘Dead’ reminds us – ‘you’re dead a long time,’ and this length becomes spatial as well as temporal when considering the dimensions that people share, whatever stage of life or death they are passing through. Where better to ponder this process but from the bed of a hospital ward, ‘with its new admission every day, / the latest freckled youth dragged / from some creek or car wreck.’ Pervasive reminders of mortality are commonplace, as ‘the salt music of insinuation,’ yet this does little to diminish their impact. Likewise, the human carapace extends into housing: from ‘semi-detached graves’ in ever-expanding settlements, to ‘the precipitous hilltop cemetery’ from where the dead appear to keep watch.

The nexus and titular poem reveals a serious accident, with physical feeling of the person (Rose’s real-life brother and star athlete) becoming quadraplegic; nerve endings deadened in a mangled wreck of metal and flesh. This poem is an understated tour-de-force along the edges that divide sentience and nothingness; worth starting or finishing a reading session, and very much vindicating the decision made to come with the poet so far. That the death of an elderly person whose discomfort has been building up for years occurs with a crash, but also in familiar, compressed surrounds elicits a wry observation: ‘eschatology is a slow / remorseless science.’ A stranger is present, hearing last words, by listening, as if to heal:

heard about a new daughter. And then the subject of feeling – why you had none in your feet. Men ground the car with steel and flung it open like a sack of wheat

These final lines of the poem recall Thom Gunn’s mourning of ‘The Man with Night Sweats,’ testament to their power and depth. The alignments of time and circumstance that some refer to as inevitability may not be anything we can understand, but their presence on such occasions creates the clarity that comes, satori-like, at the very edges of life. The poet finds himself in the public domain again, figuring out the revenant presence of a doppelgänger, from a time where: ‘in place of accidents / and crumpled youth there is / space and more space,’ yet which engenders the awareness that a seemingly untrammelled existence will eventually be brought into line. His life becomes text, so that with ‘Senza Rancor,’ no acrimony is needed (although its playful attributes form a delightful coda in the return of Catullus in the book’s final section), given all that has past:

So much happens to the living. Call it a phenomenal dust storm Visiting the land, shrouding The children who set off hand in hand Unable to read their siblings faces. Cling though we do and stumble.

The presence of death and a lack of certitudes engender a hard-won sense of humour with which to temper the personal and affecting touches that refuse to relinquish their hold on an astonishing range of immanence. The past has never seemed quite so musical, or alive.