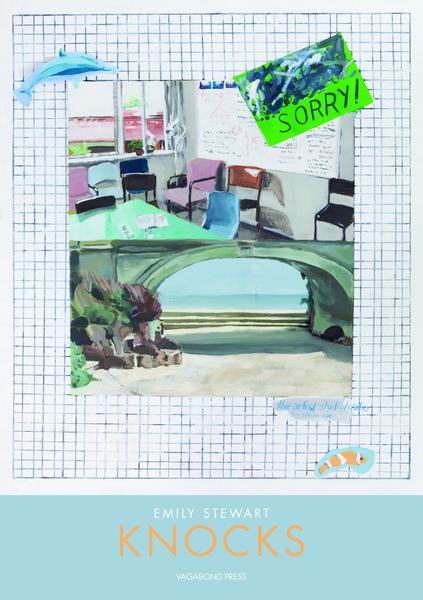

Knocks by Emily Stewart

Vagabond Press, 2016

In her 2004 essay ‘Avant-Garde Community and the Individual Talent’, Marjorie Perloff highlights the disjunction between notions of the avant-garde and its reality, specifically the problematic association of the avant-gardist as having to belong to a particular band or movement. Perloff writes:

The dialectic between individual artist and avant-garde groups is seminal to twentieth-century art-making. But not every “movement” is an avant-garde and not every avant-garde poet or artist is associated with a movement.

Emily Stewart’s Knocks operates somewhere in between these two ideas. Certainly, Stewart is part of a new wave of avant-garde poetry in Australia, and collaborative prowess is surely at the collection’s centre; but it is difficult to attach Stewart to just one particular community. Knocks pays homage to a variety of twentieth century movements: there are traces of the Oulipo, The New York School, and a certain wave of Australian poets of the late ’70s, ’80s and early ’90s that includes Pam Brown, Gig Ryan, Ken Bolton and John Forbes. However, to place Stewart as generationally aligned with just one would be a stretch, as the poems in Knocks are too various and unruly for that. But if there is one alliance that crystallises in Knocks, it is an alliance with women.

Amelia Dale writes, ‘to read Stewart is to be in the company of women’. Like Dale, Pam Brown’s launch speech cited the influence on Stewart of Arielle Greenberg’s gurlesque – a mode that celebrates, in Greenberg’s words, ‘visceral experiences of gender; these poems are non-linear but highly conversational, lush and campy, full of pop culture detritus, and ultimately very powerful’. More locally, Knocks might be read as elaborating on Melinda Bufton’s performance of the gurlesque in her debut collection Girlery (2014). In a review for Cordite Poetry Review, Emily Bitto reads the collection’s title, Girlery, as a verb, ‘something close to a feminine form of tomfoolery. One imagines a stern injunction to “cease this girlery at once!”’ Girlery then, might be considered as a feminine report of ratbaggery, a gurlish nerve that is traceable throughout Knocks.

By way of example, ‘Mobile Service’ encourages us, with obvious hints of irony and moxie, to ‘dust down a book of microwave recipes and Instagram it, with / kisses’. Elsewhere, ‘MIAuk – Baddygirl 2 MIA PARTYSQUAD BEYONCE FLAWLESS REMIX’ indulges fanfare for the gurlish heroine, the Queen B of pop. The poem presents as selected YouTube comments taken from an MIA remix of Beyonce’s ‘Flawless.’ Stewart’s poem is a tongue-in-cheek remix of the digital commentary by one female pop star on another female pop star’s anthem for female sexuality and pride. For those who don’t know (but honestly, how could you not?), ‘Flawless’ moves around the refrain:

We flawless, ladies tell 'em I woke up like this I woke up like this We flawless, ladies tell 'em Say I, look so good tonight

To add another layer to this lineage, the original ’Flawless’ contains a sample of Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie’s ‘We Should All Be Feminists.’ So by this stage that’s remix x remix x remix x remix or, remix to the power of four (cheeky, to say the least). This is not to say that Stewart’s remix is a dilution, rather, in embracing this consistent deferral it has the opposite effect: the poem’s cognisance saves it from the risk of appearing too popish; Stewart’s art of remixing is both sharp and cutting. Moves like this one might be seen as an extension of Jacques Derrida – an ode to ‘différance’. The intertextual references in Knocks embrace the various trajectories of meaning; to be involved in the communicative matrix and to destabilise meaning is a thrill for Stewart, a thrill that is transferred to her reader, too.

One might also note this drive in the collection’s second section, consisting of some of the work’s most intriguing poems. It is composed of six erasures constructed from the writing of Lydia Davis, Virginia Woolf, Helen Garner, Dianne Ackerman, Susan Sontag and Clarice Lispector. Most obviously, these erasures continue the book’s dedication, its homage to and collaboration with female poets, not only because of the source material’s authors, but also taking into consideration the history of Erasure as a form rooted in feminism. Travis Macdonald argues that our earliest encounter with erasure comes from Sappho’s fragments, ‘authored by the elements themselves … via the remnants of weathered stone carvings and papyrus scrolls; artifacts dutifully discovered, reassembled and retranslated by the scholars of every successive generation’. Like Sappho’s fragments, Knocks is direct and erotic, an agent for female desire. ‘Animal hands’ declares, ‘All I want is your mouth on my neck’, and later in ‘Baby’, ‘If what you’re imagining is sex, place me / in the whip hot tundra where we can fuck / and burn for it’.