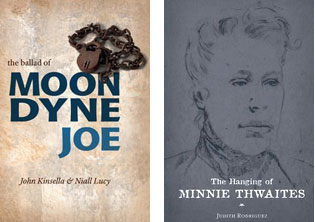

The Hanging of Minnie Thwaites

by Judith Rodriguez

Arcade Publishing, 2013

The Ballad of Moondyne Joe

by Niall Lucy and John Kinsella

Fremantle Press, 2012

Judith Rodriguez’s The Hanging of Minnie Thwaites and Niall Lucy’s and John Kinsella’s The Ballad of Moondyne Joe are informative poetic explorations of the historical figures Frances Knorr, known as Minnie Thwaites, and Joseph Bolitho Jones, known as Moondyne Joe. The books are explorations and not interpretations, as the authors are aware of the trappings of context, of interpreting fragments of text from the past according to one’s own contemporary values. Of course, this is not completely avoidable and the postmodern notion of avoiding an authoritative account is itself, arguably, a condition of context.

The Ballad of Moondyne Joe is more self-reflexive. As Niall Lucy writes in the introduction:

John and I are not historians; we didn’t set out to write about Joe in order to arrive at the last word, or to reproduce him as a unified subject whose life could be explained according to a series of causal events represented by a chronological timeline … Our Joe drifts within and across multiple temporalities …

The temporalities that Joe drifts across are connected by place: Toodyay, Fremantle, and Western Australia more generally; by the authors’ conditions of writing and their personal histories, such as John Kinsella’s ancestry; by themes of incarceration; by myths of the outlaw and of the outlaw as hero, including references to another WA ‘outlaw’ AC/DC’s Bon Scott; and by the texts in which Moondyne Joe has featured. These include newspaper articles, government documents, a novel and a film. The book contains poems in different styles, including the more abstract and playfully associative ‘Moondyne’s Masks’ (Kinsella):

Chain mail (should have seen my dreadlocks) Each link welded (individually) Interlinked (sensitivity to odours flowing through) Pre-Freud (and never a dickhead)

Kinsella also includes poems inspired by movie stills from the 1913 film Moondyne.

The result is a mentally stimulating assortment: prose, poetry and images, combining conventions of history, fiction, memoir and criticism. The ‘history’ draws heavily on the authors’ personal histories, along with the history of a myth of texts. It is not a straightforward ‘history’ of Joseph Bolitho Jones himself. The authors apply criticism to the texts, too, as in Niall Lucy’s essay ‘Moondyne Joe, As If…’, which explores the motivations of John Boyle O’Reilly, the author who wrote a novel based loosely on Joe. The essay also puts in parallel the experiences of Moondyne Joe and O’Reilly as prisoners.

The Hanging of Minnie Thwaites by Rodriguez is a more compact and subtle mix of poetry, prose and images. The history section in the middle, bookended by a ballad and lyrics, is a straightforward record, an accounting of known facts, without much interjection from the author. The history is useful for context but is nowhere near as lively as the verse. Questions are quietly raised around a spate of hangings of women, about the lack of options for women with unwanted children, and for women without means to look after children, in late 19th Century in Australia, but behind each question is the shadow of the acts that Minnie Thwaites possibly committed. And because, as the author admits, we only have some details, we cannot really form a complete picture of her.

The potential for the prose can be seen through the depiction of a minor character, the hangman. Rodriguez builds his backstory over two pages through carefully chosen details about his work, and about the fears he voiced: ‘He mentioned voices whispering that he would suffer if he hanged Mrs Knorr, but in 1894 such signs of stress did not bring psychiatric help.’ The story builds until a lock is forced and

Jones lay dead on the floor. He had hung his coat behind the door, taken a last drink, knelt leaning over the bathtub and cut his throat on both sides with a razor.

Minnie’s story is told in a plodding linear way. She is, nonetheless, a fascinating figure, and it is understandable that the author does not want to take a firm stance, neither condemning nor sympathising.

The poetry more readily takes a literary leap, closing over some of the gaps to create a picture, however stylised, of Minnie. Opening the book, ‘The Ballad of Minnie Thwaites’ is in five parts, with stanzas of four or more lines, the extra lines mainly asides in parentheses, with the second and fourth lines mostly rhyming together. As in the prose section, it tells the story of Minnie Thwaites in a linear fashion, and begins with a sly invitation to its audience – you imagine it in old times, being sung: ‘Here’s a tale to put off the babies –/Anyone thinking of getting born?’ Here’s where more of the literary guessing comes in. To fill a gap, it is assumed Minnie picked up some tricks in her first stint in jail:

One month, two months, six months, twelve months, Minnie’s taking courses in larceny, The bailiff’s man roared ‘Open and deliver!’ And shut up hope with an iron key.

In short, Rodriguez allows herself to wonder and suppose much more in the ballad and the lyrics than she does in the prose. She gives voice to Minnie, and to members of her family, her men, and others. She puts thoughts in Minnie’s head. She also brings mood and atmosphere to the story: fear, desperation, needs; the body, the seasons:

Here comes winter cold as a tombstone, The Yarra’s up and the floods are out, Here’s a winter to stare at ruin – The one thing Minnie knows – don’t get caught.