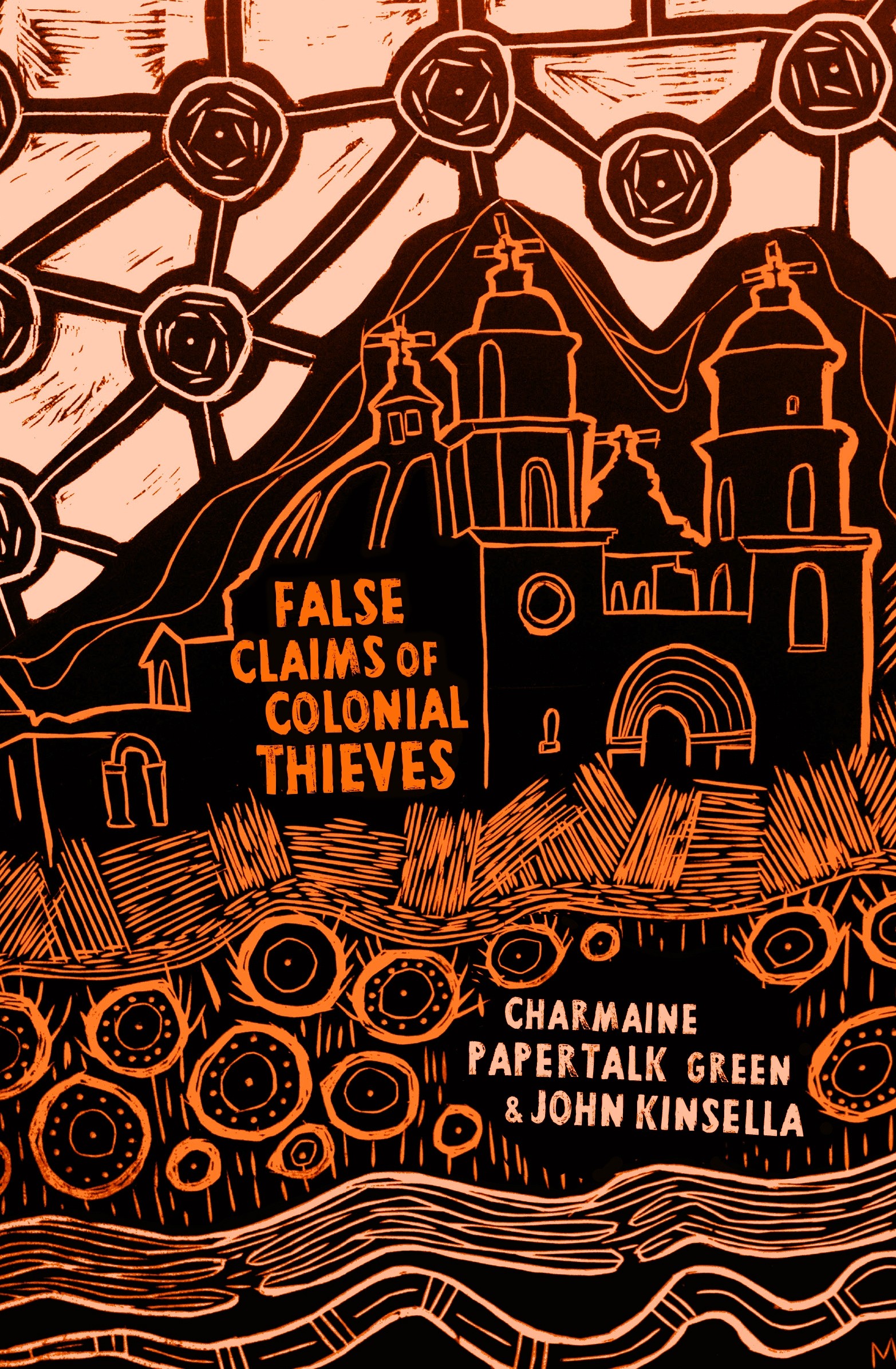

False Claims of Colonial Thieves

by Charmaine Papertalk-Green and John Kinsella

Magabala Books, 2017

False Claims of Colonial Thieves weaves together two disparate voices, Charmaine Papertalk-Green and John Kinsella, in a demanding collection that reaffirms the troubling environmental era we are living through. Structurally, the book shifts between traditionally oppositional views – an Aboriginal woman and a white man. Neither dominates the narrative: instead, we witness their shared commitment to challenge the environmental direction Australia is spiralling towards. Their concerns take the form of protest. In ‘Dream mine time animals’ Papertalk- Green writes:

Contemporary mechanical mine dream time animals Hills broken into millions of pieces Deep cuts into the flesh of earth Gapping wounds with polluted waterholes

In ‘Histories,’ Kinsella illustrates the devastation of mining with equal ferocity, writing:

Burrowing deep, Extracting gold To make it no more Then bullion – the veins Of the earth Uprooted. And the killer Goes off-site Chases a kid To his death. And the earth Cries out of the dry

These similarities suggest how their collaboration has evolved through a mutual desire to nurture our country in a time where neo-liberal mining agendas supersede social, moral and environmental consequences. But while these relationships are crucial, they exist within a history of uneven power dynamics where white Australians – however well meaning – have often spoken on our behalf. With this firmly in my consciousness, it was impossible to approach False Claims of Colonial Thieves without some hesitation. Was Kinsella aware of his privilege and the responsibilities that go with it? And had he considered the benefits of proximity that blackness might bring to his career? These concerns may seem harsh, but they are present in the minds of black Australian poets and authors.

This years Judith Wright Poetry Prize winner, Evelyn Araluen, commented on the ABC radio program AWAYE! that the [Australia’s] poetry scene initially felt like an encouraging space for black people, ‘but the more I learnt, the more I realised it was usually just about containment, possession and appropriation.’ Given the extraordinary rise and dominance of black writers – Araluen took out both first and third prize, Alexis Wright won the Stella Prize and Tony Birch received the Patrick White Award amongst a growing list of achievements by others – her words seemed to reveal the ironies of success. For a long time, Aboriginal writers have been creating some of the most exceptional work in the country, yet our identities and stories are often contained and controlled elsewhere. And, as the growing appetite for our culture rises, it has attracted some white writers who have benefited from the new black wave far greater then we have.

Given these complexities, it felt reasonable to consider Kinsella’s voice more closely, analysing the role of a white ally instead of asking people in his position to simply listen and learn? A cover quote by Bruce Pascoe alleviated my concerns, stating that the book ‘takes no prisoners, but goes into the heart of Australia’s darkness.’ As I delved into the collection, his reflections accurately described the catastrophic atmosphere the reader is thrown into. The words of both authors reveal the destructive consequences of colonisation or, more specifically, the environmental chaos mining has caused. Poems like ‘The Salt Chronicles’ demonstrate that, despite my questions regarding their pairing, Kinsella expresses a deep longing to repair the damage done to Western Australia.

Beyond the elements that unify the writers, one of the most compelling aspects of the collection is the assured way that both reflect on their stark differences. Kinsella doesn’t hide his positionality and the structural advantages he gains as mining destroys the land. In ‘Grandmothers’ he writes

My grandmother was a mining town child – … My father worked for decades in Karatha and Kal - so it’s not as if I come to the mines without foreknowledge.

In contrast, Papertalk-Green writes:

My grandmother washed White town fella’s clothes To feed her kids and survive I don think mining would have Meant much to her

These sharp distinctions ensure that the complexity of race and Australia’s cultural landscape isn’t erased. Although both are fighting for environmental justice, their connection is never constructed simplistically, and with the kind of reconciliation approach that so often becomes tokenistic gestures of unity. Instead, some of the most powerful moments are the reflections of how difficult it is for black and white Australia to unify and address ongoing injustices. In ‘I won’t Pretend,’ Papertalk-Green draws out these frictions writing:

I won’t pretend it’s easy Living in an intercultural space Cultural clashes and tensions Bounce and collide And sometimes explode

These moments leave the reader wondering how the two worked together, and what the experience would have felt like for them, responding and playing off each others work as the collection developed. These intercultural differences are articulated in one the most effecting poems, ‘Shopping Centre Car park,’ and response. Set in a Woolworths (Woollies) car park in Northam – a familiar town I have visited frequently on trips back to York where my mother’s family of Ballardong Noongar descent live – I recognised the tensions immediately, familiar with the irritable looks white people often gave mob that congregate in the air-conditioned supermarket in waves of extreme heat. Kinsella writes about this racism with a sense of disgrace and apology:

I think over this town and it’s foul history and I think over this town and the friend I have made and I say to myself Brother if you ever read this Know I admire you

But in Papertalk-Green’s response, there is no need to apologise to mob getting pushed around … instead, she shows them getting on with it:

Centre manager pushed them out But they refused to retreat to wollies car park With their get of yamajiland Pauline H banner

A major strength of the collection is its opportunity to see the colonised and colonisers’ voices in parallel, fighting for the same cause in different ways, both determined to see justice, yet never shying away from the enormous gulf that exists between them.