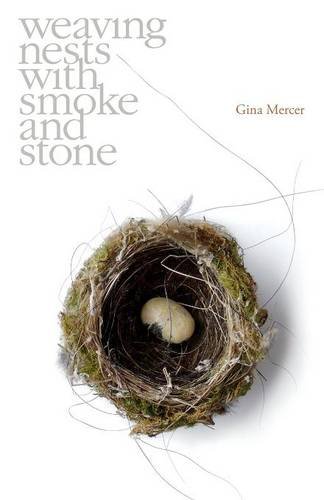

weaving nests with smoke and stone by Gina Mercer

Walleah Press, 2015

Gina Mercer’s latest collection, weaving nests with smoke and stone, is a delicate assembly of sights and sounds, visually rich and focused on the natural. Mercer’s repetition of the word ‘fossick’ throughout the collection aptly summarises the poetic processes involved. This is a collection of quick, searching movements. Lyrically deft, musical and richly preoccupied with natural elements, the poems construct meeting points for nature and humanity, ceding more and more with each piece along the way.

The domesticity of ‘weaving nests’ as a cumulative, traditionally feminine form of meaning-making and inheritance, is paired with the tangible and more fleeting materials of ‘smoke and stone.’ Historically, weaving has been associated with images of women at the loom, creating creative and more pragmatic artefacts alike. To engage with ‘weaving’ is to work within this system of purposeful creation. The collection is a marrying of natural settings and creatures with human moments and activities. Similarly, the poems alternate between entrenchment in the material and the metaphysical. Mercer’s speakers are attentive and sympathetic, engaging with issues of love and loss, as well as celebrating the natural world.

It is impossible to discuss this text without mentioning the birds. Numerous species of birds make up the focal draw of this text. Mercer’s engagements are as varied as they are frequent: birds range from being totemic, symbolic, purely ornamental, and personas in their own right. Native Australian birds set the boundaries for human interactions with the environment, but also with one another. As the collection progresses, birds become more human and vice versa. Early in the collection, there are gentle linkages specifically between women and birds: a small girl’s reverence for eastern rosellas; a family’s breakfast interrupted by sudden bird arrivals; Emily Dickinson in the mouth of a musk lorikeet; and the musings of Jenny, stricken with cancer, about the absence of birds during her trip to Italy. The delicacy of these voices and their particular connection with birdlife renders the critical tones of the collection more concrete, especially as the links become less subtle in ‘Spoonbill and swan’ and increasingly more personal in ‘The effects of immersion.’ The vulnerability of life, especially of female figures throughout the text, is strongly alluded to in these transient bird images.

The sharply resonating poignancy of the collection’s final piece, ‘After, there are the birds,’ links human experience to the natural world in a sensitive yet ecocritical reminder of the fleeting nature of life. The preciousness of transitory connections gives focus to this longer piece, overcoming divisions traditionally maintained between men/women, birds/humans, humanity/nature through shared domestic images:

He sends me photos of the singular crimson rosella who observes him through the kitchen window as he cooks dinner for one. He sends me boxes of her best clothes: designer jackets, silk shirts, tailored trousers. Asks me to share them among family even though she was the size of a wren and we’re all currawongs …

For Mercer here, birds are a recurring link to humanity and memory, for families and communities alike. The poem and the collection in general does not shy away from visceral images of decay and desolation, but these are frequently softened by these ironically humanising interactions with birdlife. The final stanza cushions some of the blow:

He sends me copies of Australian Birdlife, we speak of the plight of the orange-bellied parrot, as the wind farms of loss slice across his sky as he attempts to migrate from mated for life to flying solo. After my sister dies, her husband says, Now, there is the company of birds.

There is solace to be found, but also constant, soft reminders of loss and grief. Mercer’s exploration is as self-conscious as it is selfless, thoughtful and yet stylistically simple, approachable, and direct.

In addition to broader philosophical concerns about life and death, the collection also offers much to consider in terms of environmental and ecological awareness. Mercer’s urban spaces retain a sense of unease and tension, but not complete condemnation, as shown in ‘The geometry of change’:

Heat lounges,

a slumbering cinnamon tabby,

fur sticking to all the city’s crevices.

Pedestrian faces flush cerise

as we toil the glaring pavements.

Cool change sweeps up the river.

The cinnamon tabby arches slowly,

stalks off.

Wild and angled

hair lifts

from heat-bloated heads.

Birds and leaves zoom

random trajectories

across the crazy air.

The town shrugs, brushes itself off,

revels in the anarchy of wind.

Mercer’s treatment of the introduced predator is far less unfavourable than may have been expected from a collection so given over to birdlife, but still fraught with concern. The introduced species, like the urban space, is not as overtly mobile within the broad notion of the environment as the birds and tree leaves, yet still imbued with an overarching sense of potential for development and positive change. The ‘cinnamon tabby’ is in a state of flux, but clearly allied with the rigidity of the urban setting. However, as an introduced animal as opposed to strictly human element, it is not treated with the same kind of suspicion as that which is shown, in other poems, towards other introduced presences. Workers are uncomfortable presences, while the speaker alone enjoys some form of connection with the environment in ‘Cool velvet underfoot’:

Monday morning, the park is active.

Lean executives jog relentless,

cyclists commute, flashing diligence,

middle-agers circumnavigate in comfort-plump shoes.

Arid and tired,

I step feckless,

my feet tasting

the cool velvet of grass.

Too exhausted to muster a goal,

my hungry arms angle round my ribs.

Ambling aimless – I am the park’s only epicure.

Even the sky is in peak-hour frenzy:

six ibis speed an invisible path

like girls cycling late to school,

an arrow of magpie geese creaks off to work.

Only that kestrel looks weary as it flap flap glides

home from hunting the night.

Apart from me and a worm-supping, dew-sipping peewee,

no one enters the park’s centre.

All so purposeful, oblivious,

so busy, skirting,

this simple,

grass-gorgeous park.

Structurally and tonally the speaker is removed from other human presences, linked more firmly with the birds and plants managing to thrive in this inner-city space. Here, birds are totemic, but also humanised – indeed, far more than the ‘human’ figures that appear in the first stanza. While the birds are still clearly linked with human experiences, the close attention to detail they receive clearly articulates Mercer’s ecocritical sympathies, as well as her rich understandings of human relationships and emotions. This is a space that deserves greater appreciation, and these are figures are require closer attention. Mercer treads a careful line between respect and conscription, and is successful in presenting a piece that is equal parts criticism and celebration.

A delicate investigation of what is not essentially human, weaving nests with smoke and stone is a neatly lyrical collection that carefully explores love and loss, with an eye to the natural world for support, but also level-headed awareness of human responsibility.