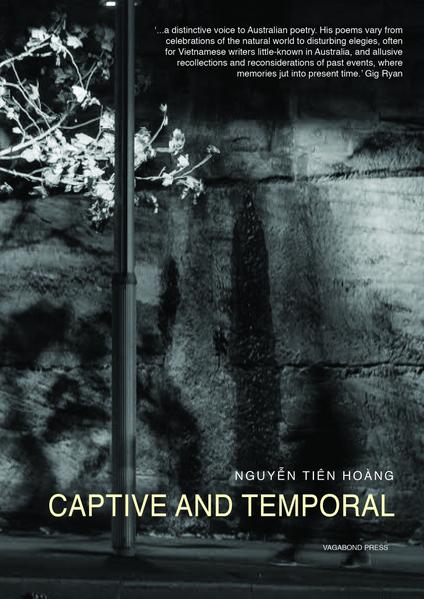

Captive and Temporal by Nguyễn Tiên Hoàng

Vagabond Press, 2017

It’s with an almost exquisite eccentricity that Nguyễn Tiên Hoàng’s Captive and Temporal unfurls, immersing the reader in a discursive cartography over composite planes of memory, history, heritage, culture and dreams in surreal and interpenetrative riddles, dedications and elegies. With one eye open to the telescope, the other open to the periphery, Nguyễn’s distinctive poetry charts unexpected co-ordinates in a constellated pitch somewhere between historical materialism and an intuitive, sensuous phenomenology. It opens:

NOVEMBER, END OF A STREET, MELBOURNE Islands forming clouds and miniscule breaking eddies, washed in first lights, an avenue of trees, full and abundant a jaywalker among volumes and cubes.

A lot of the titles of the poems in the collection read almost as titles to artworks. They are gnomic run-ups to an image/performance/installation. Rather than labelling a poem, here they launch the reader into them. The above poem rolls poetically enough from its blunt title, into a dreamy evocation of energy as a water-like flux, anticipating the end of something – Spring? Maybe said street? – or is it a beginning? Light is new, the trees are healthy, established, ordered. Then: ‘a jaywalker’, among adjective-less forms and geometries. This is weird, and an opening example of the idiosyncrasies in Nguyễn’s poetry.

Nguyễn’s bio mentions he migrated to Australia from Vietnam under the Colombo Plan Scholarship in 1974. In Vietnam, a pedestrian getting across the road according to their own judgement and wits is just the way it is; in Australia, it’s a legal transgression, albeit a minor one. With this, the ‘jaywalker’ becomes a rapid signifier of a sense of estrangement and association, a foreigner among foreign forms whose transplanted customs and culture make an enigma of arrival (to hijack a De Chirico painting title). The place of arrival is a mutable site, in this case itself the result of an invasion/incursion and an imposition of foreign orders and laws. Site and person meet as a consequence of war and violence centuries apart.

why the other side? you can’t answer, you simply look books of histories diaries of survivors memoirs of retired generals, men of war games

Living, lived and petrified records of victors and their disposable subjects then become fetishised in a vitrine or bookcase:

stacked up nicely in a full frame behind impossible glass

The skittered use of parataxis and enjambment throughout the poems communicates these unpredictable transversals and polyvalences. Peculiar words jolt as pivot or checkpoints. At these points, the schema of the collection surge and cascade in, out and through and, at any moment, Nguyễn’s seemingly disconnected elements and symbols are presented less as disparate layered things than as squashed together between the slides and slotted under the gaze of a microscope.

The lines are immediately imagistic, cinematic even, then the real poetry starts to take hold as recurring motifs and themes are repeated and re-inflected through inventive metaphor, each time angling us into a new perspective where these folds and creases become another avenue of scrutiny.

In ‘Autumn Writing’, Nguyễn crafts a stunning meta-poem. It also serves as a nexus for several strands of ideation. He attempts to test the medium while remaining faithful to its traditions in the promise of uncovering verity.

Can one simply write about a fire to warm up a morning, that perfect vault of sky?

From this poem, autumn, fire, skull, high grass, even cattle are cast repeatedly into the rest of the collection. And when you come across them, a new interpretation colours the preceding one. The fire in the opening line here, surrounded by the words ‘autumn’ and ‘warm’ can be read as a pastoral ritual: burning-off time. The bucolic sense of chilled air with a scent of wood smoke has a cosiness to it. Writing as a leisure pursuit where there’s time for philosophising. Then ‘grey coarse ash / falling from the rough skin’. Something’s happened. Fallen red, orange leaves and autumn’s ablaze? But the colour has gone. Seeing ‘seneca’ above ‘white noises of rotor blades / to the sea and wagner’ a few pages on (‘APRIL’) throws me back to take a pile of burning leaves as the stoic self-immolation of Thích Quảng Đức. The Vietnam War? Napalm? The poet’s been attacked? He’s in a war zone? Poetry is getting serious as the disquiet of the unconscious memory and present poke about. A head enters:

simple, concrete, a head of a person, an animal moving in the neck-high grass

,

but it’s not so simple; even something concrete ain’t so concrete enough to hold down. The high grass conceals something, it drowns the body, which is choking as a figure ‘takes aim … Now, the heart of a cross (+) / A sound, terse, metallic’. High noon for subject and object. Things intersect.

But this is not a poem, this is an alphabet F Like a bullet nudged into a cartridge: F! F? Faust? Or Fate? or Fortissimo? FIRE!

It’s all only matter, perhaps. Words, letters are expendable in the pursuit of resolution. They furnish the confluence of events that cause both private and public attritions. (I read the above passage in my head as a kind of Taxi Driver soliloquy). Each letter may be no more useful than a wasted bullet after an elusive target, or a reckless spray in fear or last-defense, or anger. Joy? Each poem is no more than a jot in the body count ‘wincing from thousands / heading a scurry / to the footnotes’ (‘APRIL’).

The use of a polyseme; ‘FIRE!’, is another example of how Nguyễn sets a point that launches new lines of interpretation. Is it a warning? An order? A noun? Verb? An element? A transcendental gift? The high grass is not solely incidental as setting for a shoot-out. Nor is it just an ominous presence as flammable environment. Nguyễn brilliantly flattens the field of vision. In the last stanza of ‘AUTUMN WRITING’, the phrase ‘out of the clearing of the wood’ hints at a threshold, but again, it’s not as metaphorical stage set. Two pages later, there appear ‘bites / Neanderthal, but ewes [& carcass] and crows heralding / daybreaks’ (‘QUAGMIRE’), adding a few scattered Paleolithic references – the crossroads of our genealogy. This is where the changing climate saw the Neanderthal need to leave the forests to survive and, ‘like a toddler, before yet / another fall’ (‘AUTUMN WRITING’), take to the plains where Homo sapiens was better suited.